Mystery Illnesses Writ Large

From LA Review of Books as Mystery Illnesses Writ Large:

December 24, 2021 • By Jeff Wheelwright

/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2021%2F12%2Fthesleepingbeauties.jpeg)

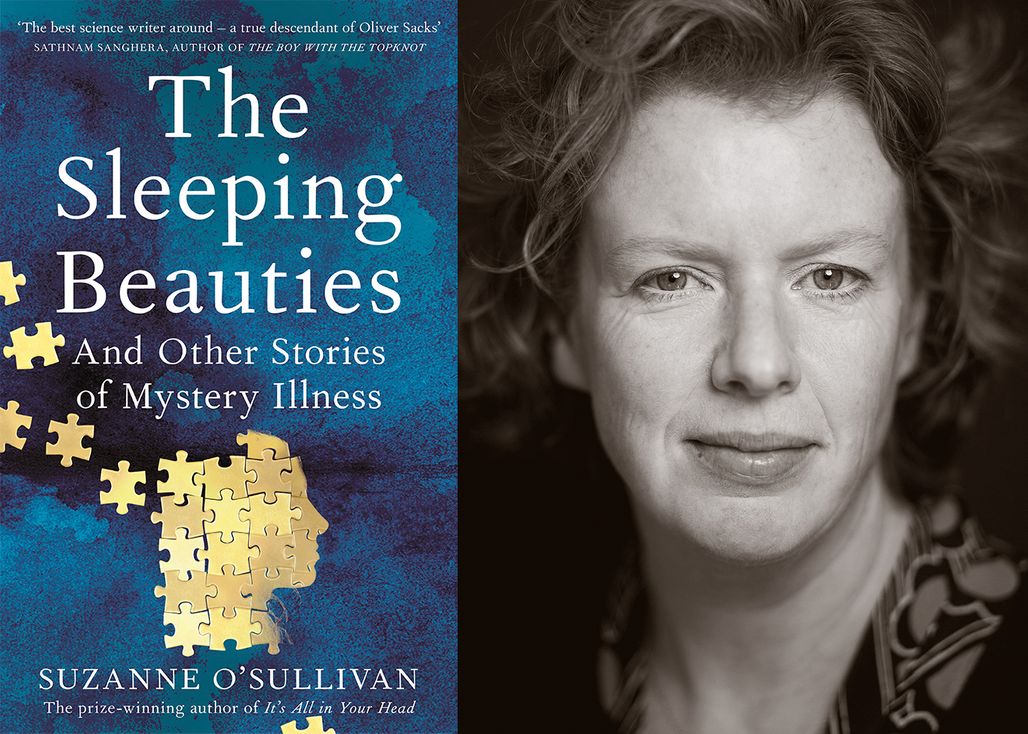

The Sleeping Beauties: And Other Stories of Mystery Illness

SUZANNE O’SULLIVAN

MASS PSYCHOGENIC ILLNESS (MPI) is the formal name for incidents of “mass hysteria.” The outbreaks are a favorite topic of the popular press, but they are poorly understood. A cluster of strange illnesses that appear to have an organic basis are shown, after further scrutiny, to be a psychosomatic fabrication by a close-knit group of people. Most of the time this finding neither assuages the patients nor resolves the controversy.

Suzanne O’Sullivan, a neurologist who works in London, has written a useful and entertaining account of MPI. The Sleeping Beauties: And Other Stories of Mystery Illness is her third book of medical brainteasers, and I’m not being snide in deeming it a great beach-read. Born and raised in Dublin, O’Sullivan has the vaunted Irish command of storytelling. Her book can be picked up and put down without losing your place, your sunscreen, or the drift of her argument.

O’Sullivan insists that MPIs are not fabrications in the sense of being made up or faked. They are both frightening and real, she says, even if they don’t make sense to conventional doctoring. The reason they don’t make sense is that modern medicine permits no middle ground between objectively measurable disease and the psychological projections that some of her colleagues dismiss as “time-wasters.” “That the body is the mouthpiece of the mind seems self-evident to me,” she states in her preface, “but I have the sense that not everybody feels the connection between bodily changes and the contents of their thoughts as vividly as I do.” “Every medical problem,” she continues, “is a combination of the biological, the psychological and the social. It is only the weighting of each that changes.” And with that, she’s off to investigate recent MPI incidents in Sweden, Kazakhstan, Texas, Colombia, and other far-flung places.

More often than not the patients she encounters are impressionable girls, a skew O’Sullivan explains with only partial success. Her title story is about scores of young girls in Sweden who, starting in 2015, took to their beds, closed their eyes, and became inert for weeks and months on end. For want of a better name, the puzzled doctors called their illness “resignation syndrome.” We meet 10-year-old Nola,

[h]er hands […] folded across her stomach. She looked serene, like the princess who had eaten the poisoned apple. The only certain sign of illness was a nasograstric feeding tube threaded through her nose, secured to her cheek with tape. The only sign of life, the gentle up and down of her chest.

The child submits to basic probes as limply and mutely as a corpse, but except for a wasting of her body the Swedish doctors can’t find anything wrong. Far from comatose, Nola has a heart rate over 90 and her teeth are clenched. What could be going on inside her head? O’Sullivan enters the girl’s home suspecting a psychosomatic illness, and a few pages later (spoiler alert) reveals that the sleeping beauties all happen to be children of Middle Eastern refugees seeking asylum. Due to a hardening political climate in Sweden, the families are facing deportation. Whether or not the children recognize their motives is beside the point — their physical reactions are extravagant, dangerous, and beyond their control. Still, the key to the mystery having been provided, the narrative in this lead chapter is somewhat anticlimactic. Better and more bizarre stories follow.

Suzanne O’Sullivan has gained a solid reputation in the United Kingdom and Ireland as a doctor and writer. Having seen patients at neurology clinics for more than two decades, she found that one in four who believed they had epilepsy really do not, and that, overall, one in three people with neurological complaints suffer from a psychosomatic disorder of one kind or another. Her uncovering of “pseudoseizures” prompted her first book, It’s All in Your Head: True Stories of Imaginary Illness (2015). She got into a sticky wicket for including a chapter on chronic fatigue syndrome, sometimes known as myalgic encephalomyelitis. CFS/ME patients strongly disputed a psychological basis for their symptoms, and they pushed back against the book. When it came out in the United States, an equivocating question mark was added to the title: Is It All in Your Head?

O’Sullivan’s second effort, Brainstorm (2018), steered back into the safe harbor of organic neurology, while inverting the medical premise. This time the case studies were of patients who seemed batty on examination when in fact they manifested the rare or unique signs of epilepsy. Truly it was their neurological seizures that made them act strangely. With Brainstorm, critics anointed O’Sullivan as the successor to the British American neurologist Oliver Sacks. Sacks, author of the The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, died in 2015. He set a high bar in popular medical writing, producing a dozen books that danced charmingly along the mind-body interface.

In Sleeping Beauties, O’Sullivan establishes her own mind-body purview. “Our brains are so clever, we don’t even know what they are up to,” she notes dryly. She opposes freighted terms like hysteria and even psychosomatic or psychogenic because labeling has been used to undermine patients who are in pain and to derogate female patients in particular. Her preferred term for the individual case is “functional neurological disorder,” or FND, which comprises both the quantifiable body (“neurological”) and the elusive mind (a “functional” disorder can’t be explained organically). Another term O’Sullivan likes is “dissociation,” which she defines as “a disconnection between memory, perception, and identity […] without brain disease.” In dissociation, the rational mind does not discern what the body is up to, even as the irrational mind operates like a malign puppeteer jerking the body’s strings. A mass psychogenic illness consists of FNDs writ large.

For the most part, O’Sullivan’s jargon goes down smoothly. To make things easier, she constructs each chapter with the same format. Arriving on the scene, the jet-lagged O’Sullivan meets a patient or two and presents the initial details of the “mystery illness.” In the few instances where she doesn’t travel in person, she summarizes the initial press accounts, which are either inaccurate or unhelpful. Then she gives background, emphasizing the cultures in which the illnesses have broken out. For example, the sick people in Kazakhstan come from two towns that were uprooted after the collapse of the Soviet Union. In rural Colombia, where schoolgirls have been fainting and difficult to revive, the villagers are upset about the government’s vaccination program for human papillomavirus (HPV). After providing clues that point us away from what the local doctors think, O’Sullivan dives into the patients again. She offers her own, much more persuasive explanation for what has happened to them. Almost always the patients are starting to recover, the emergency in retreat. As she heads to the airport, O’Sullivan wraps up each case with a rather dutiful summary of the lessons learned, just as your own doctor will summarize what they have told you about your health at the end of your visit.

MPIs are difficult for medical professionals to grasp because each stems from unique cultural conditions. For O’Sullivan, context is more important than symptomatology. “Outbreaks of mass psychosomatic illness happen all over the world, multiple times per year,” she notes, “but they affect such unrelated communities that no one group gets the chance to learn from the other.” She pulls together a number of common elements. For one, the MPI contagion is usually sparked by an index case, a person whose flagrant physical symptoms are unwittingly copied by others, though not replicated exactly. She calls this “embodiment and predictive coding.” Two, the local physicians, who are mystified for a while, seize upon a cause, usually a toxic exposure or other external agent, and then double down when they are challenged. If news reporters descend, the community becomes defensive and rejects the charge of mass hysteria.

Havana syndrome, in which US and Canadian diplomatic personnel feared they had been attacked by a sonic weapon wielded by the Cuban government, provides an interesting and unusual case because it involved a medically sophisticated population. Symptoms, shared by men and women alike, include headaches, dizziness, memory problems, and hearing issues. A crucial factor, according to O’Sullivan, is that one of the American medical researchers on the scene had a military background, which led him to associate the health complaints in and around the US embassy with the traumatic brain injuries (TBI) that occurred in the blast zones of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. TBI itself was a slippery diagnostic entity, and at any rate was the wrong tack to take, she maintains. It was biologically implausible to attribute the symptoms in Havana to the impact of sound waves or microwaves. For one thing, such weapons would have burned the skin.

Commenting on a 2018 paper in the Journal of the American Medical Association, O’Sullivan writes, “Despite the paper’s emphatic conclusion pointing to a brain injury, none of the tests described in the JAMA paper actually proved that: the brain scans were all normal.” More likely, political pressures and stressful working conditions were to blame for Havana syndrome. “As is often heard said in medical circles, ‘When you hear hooves, think horses, not zebras.’ Functional disorders are common. Sonic weapons are not. How was an everyday diagnosis sidelined for one that many thought impossible?” That the Havana symptoms have since been reported at other American missions only strengthens O’Sullivan’s argument.

O’Sullivan could have profited from linking Havana syndrome with mysterious military illnesses that occurred even earlier than TBI, e.g., those affecting some of the troops who served in the 1991 Persian Gulf War. In the case of Gulf War syndrome, a subject I’ve excavated in considerable depth elsewhere, a different set of pressures fueled a similar suite of nonspecific ailments.

The children and teenagers in O’Sullivan’s accounts are unwitting; the adults feel shame and anger if tagged with a functional or psychogenic diagnosis. Here the professionals, who often are conflicted themselves, aren’t of much help. “Psychological illness, psychosomatic and functional symptoms are the least respected of medical problems,” asserts O’Sullivan. When dealing with shape-shifting symptoms, doctors don’t like to tell patients, “I don’t know.”

Especially in the West, doctors do a better job at creating new medical entities like attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or autism spectrum disorder (ASD) than they do in plumbing the old ones. “That is Western medicine’s culture-bound syndrome — we make sick people,” O’Sullivan says somberly. “We medicalize difference, even when no objective pathology is available to be found. […] Medical conditions in the Western formulation have a tendency to become chronic. They are labels that one can never completely shake.” I would go further and suggest that FND sufferers welcome and defend their biomedical labels, hoping that sooner or later the doctors will deliver an objective pathology, to be followed by a pill or some other relief from their long-running, elusive conditions. Chronic Lyme disease may belong in this category.

Methodical and careful, Suzanne O’Sullivan is quite a different cat from the late Oliver Sacks. He was a warm and flighty fellow whom I came to know briefly. I once assigned Sacks to write a magazine profile of a young man with Tourette’s syndrome. Before they got under way, I asked the two to meet with me in my office. Tourette’s is a neurodevelopmental condition that causes unwanted tics, coughs, twitches, yips, and occasional cursing. As writer and subject sat there, Sacks and the young man set each other off. Each emitted abrupt noises throughout the meeting. I might as well have asked the Tourette’s man to write a profile of the jumpy, zany, bespectacled doctor.

If I could put Sacks in the same room with O’Sullivan, I’d ask them to discuss the gender skew that characterizes functional neurological disorders. Though she mentions it often, O’Sullivan never digs into the fact that, across cultures, women and girls are much more likely than men or boys to evince dissociative symptoms. She comes near an explanation when she says, “There are many factors, but I am convinced that [women’s] voiceless position in society is one of them.” Denied an equal role in patriarchal communities, women and girls express distress and suffering through their bodies. Paging Dr. Freud: Does that make them hysterics?

As to the sleeping beauties in Sweden, O’Sullivan says, “The resignation-syndrome children […] are unconsciously playing out a sick role that has entered the folklore of their small community. And: “Resignation syndrome is a language that I haven’t yet learned to speak. It exists to allow the girls to tell their story.” Hearing all of this, Sacks might have perked up and mused about the girls’ heroic plasticity: children in a foreign land they cannot have understood were sacrificing their bodies in order to help their parents remain. Sacks might have propelled resignation syndrome into a higher orbit, converting an illness into an oddly shining gift. A nonfiction writer with scientific chops, he was willing to take risks. O’Sullivan has a different agenda, perhaps a more responsible one. Assuming that she keeps writing, she may yet produce wonderful literature.

¤