Andres Serrano: Beyond The Pale

Andres Serrano: Beyond The Pale

Andres Serrano interviewed by Robert Horvitz

‘America & Trump’ opened at the Groningen Forum in the Netherlands on 23 March and will remain on view until 5 November 2024. This YUGE exhibition brings together three projects by Andres Serrano: 30+ large-format photo-portraits of Americans from all walks of life, The Game: All Things Trump (2019)- more than a thousand Trump-related artifacts, souvenirs, memorabilia, merchandise and campaign materials that Serrano bought at auction or hoovered-up through eBay, and, “Insurrection” – Serrano’s 75-minute compilation of historical film footage, on-site smartphone recordings and TV news clips about the assault on the US Capitol on 6 January 2021.

The show is attracting a lot of attention, not least because of the new Dutch government’s Trump-ward lurch and Serrano’s photo of a scowling Trump on posters all over the city, often defaced with a Hitler moustache added by a local graffiti artist. Memories of Serrano’s controversial 1997 show at the Groninger Museum (“A History of Sex”) have been revived by this new provocation, which follows a much praised retrospective at DOX last summer in Prague, where this interview was recorded on 10 June 2023.

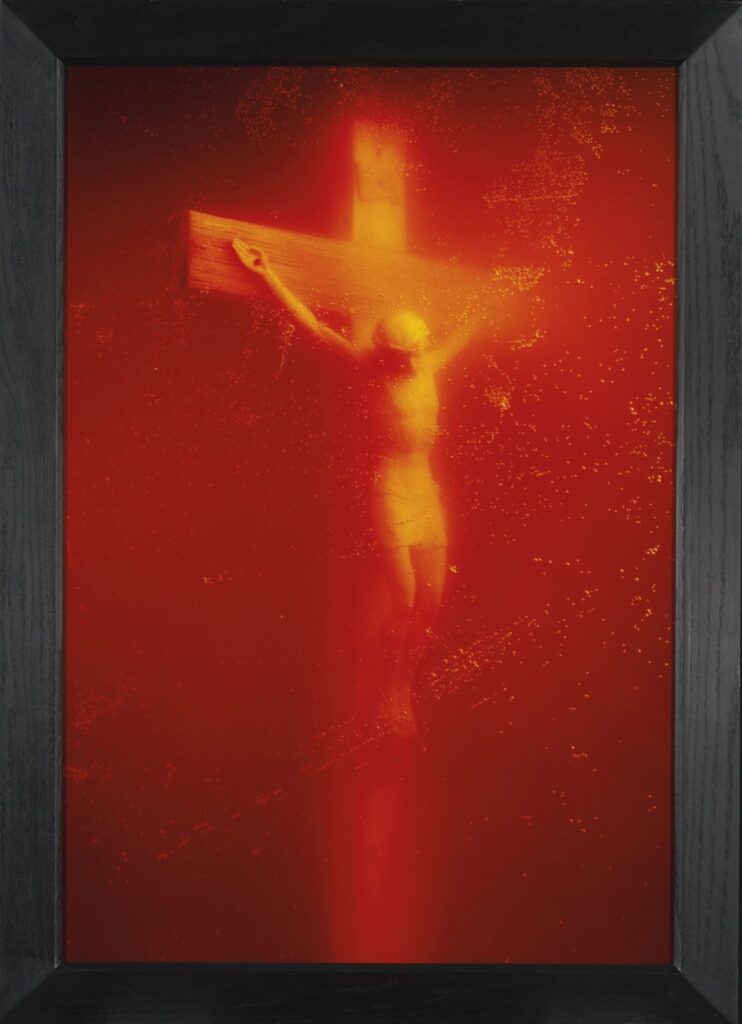

Robert Horvitz: Like most people, I first heard of you in connection with Immersions: Piss Christ (1987). That piece didn’t come out of nowhere. There must have been a path leading to it. Could you say something about how you got to Piss Christ?

Andres Serrano: In 1965, when I was 15, I dropped out of high school. Two years later I went to the Brooklyn Museum Art School where I studied painting and sculpture. After two years of school I wanted to continue being an artist, but I couldn’t really paint the way I wanted to and I didn’t have a studio for making objects. But I lived with a girl named Millie Ehrlich, and she had a camera. So I started taking pictures with Millie’s camera. I did it as an art practice, not as a photographer. I never was interested in the actual process of photography. I never went into a darkroom. My technical knowledge of photography is rudimentary. I’ve had the same camera, a Mamiya RB 67, for 30 years. I’m not one of those guys that are interested in the equipment and invests a lot of time getting to know everything about the zone system, lighting, and all that. I’m just using photography as a tool, as a means to an end. I’ve always said I learned everything I know from Marcel Duchamp, who taught me that anything could be a work of art, including a photograph. So that’s why I call my work ‘pieces’. I never call them photographs.

But you clearly can get the shot you want

I have assistants. I shoot on film, not digital, so it’s a lot of Polaroids that I have to take beforehand. Last January I did an assignment for the New York Times Magazine, photographing fighting cocks. Roosters. I had to get the assignment done. I had to get the shot, so I didn’t have time to take Polaroids. So for the first time, I did digital work. My assistant is a digital guy. We rented equipment so that I could take the picture we saw on the screen of the small monitor. That made sense because I couldn’t fuck around taking Polaroids, waiting for the birds. They’re not like human beings where they sit still and you take a Polaroid to check the light. You can’t tell the bird don’t move, stay in that position for two minutes.

In the Nomads (1990) and the Infamous (2019) series, it’s clear that you picked the people. But Andy Warhol, for example, made a lot of money doing commissioned portraits. Do you accept commissions for portraits? Isn’t that like a magazine assignment?

I don’t consider editorial work the same as commercial work. I would do commercial work–I could use the money–but I rarely get asked. Once in a while, some charity asks me to donate a portrait for a benefit where someone bids, and then the money goes to the charity, not to me. Usually it’s been like 25 grand. I’d love to do commercial work–if it’s the right work–but I don’t get asked. And I’m happy with that. I’m happy to just do my own work. I’ve always said I’m not a photographer, I’m a conceptual artist with a camera. But getting back to Piss Christ, that saga really begins with Marcia Tucker and Bill Olander. She was director of The New Museum in Manhattan, and he was one of the curators there. They loved my work, even though I was unknown. Unbeknownst to me, Marcia nominated me for the national Awards In The Visual Arts. This was a competition based at SECCA, the South-Eastern Center for Contemporary Art in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. They asked each curator or judge to nominate five people. And so I get a phone call in 1988 telling me that I won this award for individual arts for New York City. I couldn’t believe it. I’m completely unknown and I get this award. The award was based on ten slides that I submitted, and Piss Christ was one of them. In addition to the $15,000 prize money, there was an exhibition that would travel with each of the artists. And because I had submitted Piss Christ as one of the slides, I gave that as one of the works for the exhibition. Piss Christ didn’t get any attention until the show got to the Virginia Museum. During the show a local newspaper published a short Letter to the Editor. I had been asked to do a walkthrough and talk about my works there. The man that wrote the letter was in the walkthrough group and he wrote to the editor protesting Piss Christ, saying that the National Endowment for the Arts gave money for this horrible picture.

It was a photo, not an actual bottle?

Right. Piss Christ is always just a photograph. You’re not the first person to think that it was originally a sculpture. But no. There was never any object presented as the work. And also it was not a jar, it was a tank full of urine. Anyhow, this Letter to the Editor caught the attention of the Reverend Donald Wildman, who was head of the American Family Association, a very right-wing religious Christian organisation, and he sent out 178,000 letters to his people asking them to write to Congress to protest the use of taxpayer money in this way. So, in April of 1989, I see for the first time in the New York Post, ‘Big Storm over Piss Christ‘. Congress, Senators started to get angry letters about this photograph that they heard was sponsored by the NEA which paid $15,000 to create it. Not true. The Rockefeller Foundation and the Equitable Life Assurance had given two-thirds of the budget for the exhibition and the SECCA award so really, just $5,000 of the money given to me came from the NEA. But because of all of this hoopla, in May 1989, I start getting denounced in Congress by Jesse Helms and Alfonse D’Amato. I have a clipping from the Congressional Record where D’Amato rips up the exhibition catalogue. He says, “If these art world crazies can get away with this, there’s no telling where they’ll go.” After he does this, then Jesse Helms pops in and says something which has always been one of my favourite quotes: “Andres Serrano is not an artist. He’s a jerk who’s taunting the American people.” Now, I’m completely unknown as an artist. I’m lucky I got this award. And the idea of me standing in front of the American people taunting them, it emboldened me. It really made me feel good that I had so much power that I could do this and take the heat. I started to get death threats, but you know what? I felt like I can take the heat so I’ll stay in the kitchen. And I’ve been in the kitchen ever since.

The effect of Piss Christ as a photograph is so different from what I had imagined, thinking it was a sculpture. You must have realised the advantage of using photography, not just to get more copies, but to get a completely different reading than presenting a flask of urine with a plastic Christ in it.

Well, absolutely. And if the image was a painting, it would be different again. It wouldn’t have the same power. A red monochrome: if it’s a painting, big deal. But the fact that it’s a photograph of real blood, and when people know it, that makes a big difference. Even though I make it look like an abstract painting, it’s a real thing. A painting called ‘Piss Christ’ isn’t the same as a photograph because photos have more credibility.

That’s even more true of the photos looking down the barrel of a gun.

Exactly, and a loaded gun, too. In one of the pictures you can actually see the bullet in the chamber. When we were setting up, my assistant Blake Boyd told me to be careful because the gun is loaded. I said, “Great. I’ll shoot it that way.”

It’s such a powerful image. When you first see it, you think how much it’s like an abstraction. But then, when you realise what it is, it’s not abstract at all. It’s very real.

Maybe it’s also a metaphor for my work: that sometimes it can be dangerous, depending on who sees it and how they react. I had an exhibition in London of A History of Sex and five Neo-Nazis destroyed some of the pictures. They went into the exhibition with sledge-hammers and one of them filmed the action. They actually made a video of the whole thing, put heavy metal music to it with Nazi anti-degenerate art slogans at the end and posted it online. Piss Christ has been vandalised several times. Now it’s been taken out of one high school’s curriculum. Other schools could follow suit in a chain reaction: one complains then another gets the idea and complains. Showing Michelangelo’s statue of David got a teacher and a principal fired. That to me is absolutely unbelievable. Ignorant individuals should not have the power to censor everyone else, but apparently they do. That’s the real crime for me.

You see yourself as an outsider yet you’re also commercially successful. Is that a hard duality to maintain?

It all depends on where you are in life. For me, the notion of the struggling artist is very real. When you’re unknown, you make very little money and you need very little. When I was young, with $50 I could get props and do two or three pictures. Then, as you get older, you make more money but you have higher overhead. Now, you don’t need $200 a month, you need thousands. I’ve been fortunate, but at the same time, because I don’t have a New York gallery–I mean, I show with the Baldwin Gallery in Aspen [Colorado], but other than that, I’m not represented by any American gallery. And for a New York artist to not have a New York gallery, it’s difficult. Still I’ve been very, very lucky that I’ve been able to survive in this jungle. I was with the Paula Cooper Gallery from 1990 until 2008, and then I got mad at Paula about something very stupid. I got mad in such a way that it severed our relationship. And since then I haven’t had a New York gallery. For 5 years. Seven years ago I had a show with Jack Shainman, but it was a one-off. I was with Yvon Lambert for more than 20 years, until Yvon closed his galleries in Paris and in New York. The fact that I had Paula and Yvon gave me something. Without them I’m an outsider, speaking of the art market, so it’s difficult. I’ve been fortunate in still having museum shows all over the world, mainly outside the US, thanks to Nathalie Obadia. The last big show in America, my only real show, was the one that travelled in 1995. It started at the LA County Museum and went to the Virginia Museum and then the New Museum.

Is the Prague show your largest to date?

No, the largest show I had was at the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Brussels, about 5 years ago. That gallery was huge. But the Prague show is one of the best. They got special lighting like I requested, nice warm lights, and they made every effort to light the work the way I thought it should be. Otto Urban, the curator, Leoš Válka [DOX’s founder] and Michaela [Šilpochová, DOX’s program manager], put together a fascinating selection in a very unusual way. The other day I had the former director of the Pompidou here and he said, “I’ve known your work and seen many of your shows, but this one made me look at your work in a different way.” Meaning there was an opportunity here to reinvent yourself and your image. That’s because of Otto and the other people involved in the show, the way they put it together. It’s one of the best, I think. I want curators from other countries, even America, to come see it, to get an idea of what a show could look like.

So it was their selection of works, not yours?

Yeah, it was their selection, based on what we could get. We couldn’t get a Piss Christ but we got the NFT. I wasn’t involved in the selection as much as Irina [Movmyga, Andres’ wife] was. She followed the thread of emails more than I did. A lot of what they got came from the a/political organisation in London. They’ve helped me tremendously. They own the big Torture pictures. Also, Nathalie Obadia has a lot of my work in storage. And some pieces came from New York. I have a lot of work in storage, from Paula and from other places, because there were times when I had so many shows going at the same time that we had to produce more images, and then they get back to me if they haven’t been sold. So the Prague show is like a “greatest hits” exhibition.

How did this show come about?

Irina Movmyga: Otto contacted us through our website, 6 years ago. At the time he was working as a curator at the Czech National Gallery. When he left the National Gallery, he still had the idea to make a Serrano exhibition. Then he started working at DOX and it happened.

AS: When he started working with us, we talked with other people who had lots of works. He had a selection of things that he wanted and it was just a matter of finding them.

IM: Three different places loaned works: the Obadia gallery in Paris, a/political in London, and the whole “Infamous” exhibition–35 pieces from Fotografiska.

AS: They produced the “Infamous” show. They have museums in New York City, in Stockholm and Tallinn. In New York they pulled the “Black Man Lynching” picture and several other images at the last minute. I was surprised because they paid for the printing and it cost several thousand dollars to produce each piece. But in Stockholm they showed all of them. Because the show existed and they didn’t know what to do with it after it closed, I thought “Infamous” should go to Prague and Otto was happy to get it.

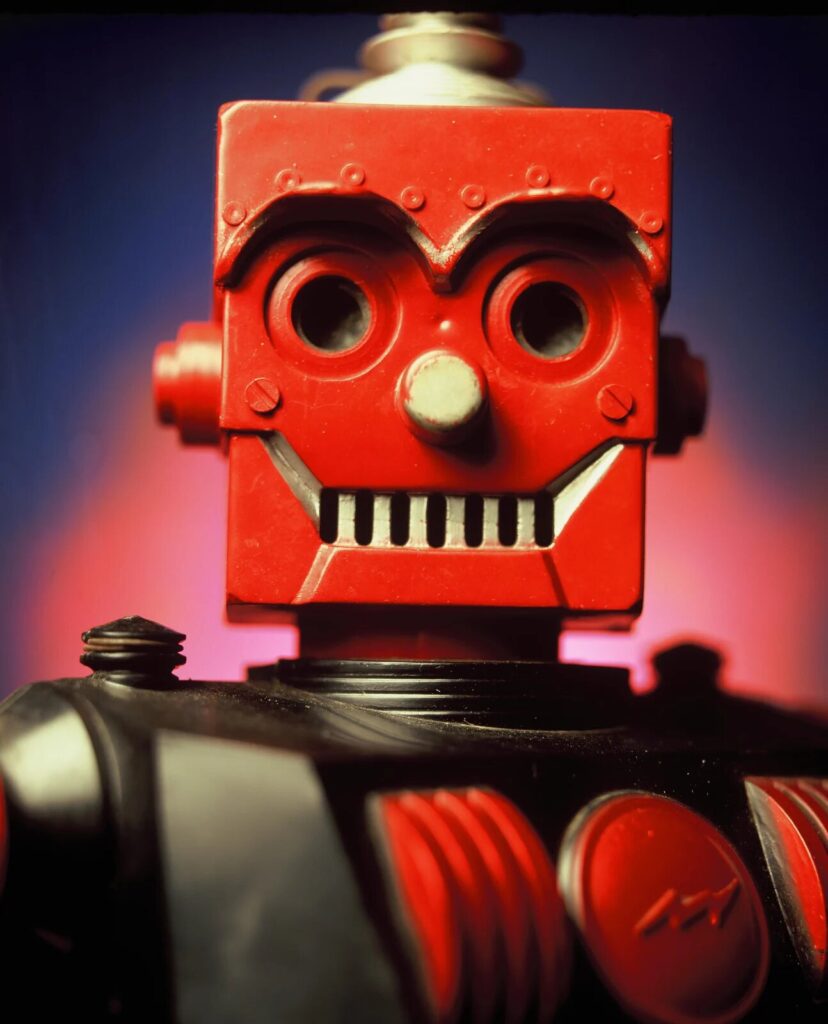

A lot of the work in the Prague show seems to be from the 1980s, but The Robots (2022) series is from last year. The show isn’t organised chronologically, so it isn’t obvious how your work evolved. Can you explain how it’s changed over time?

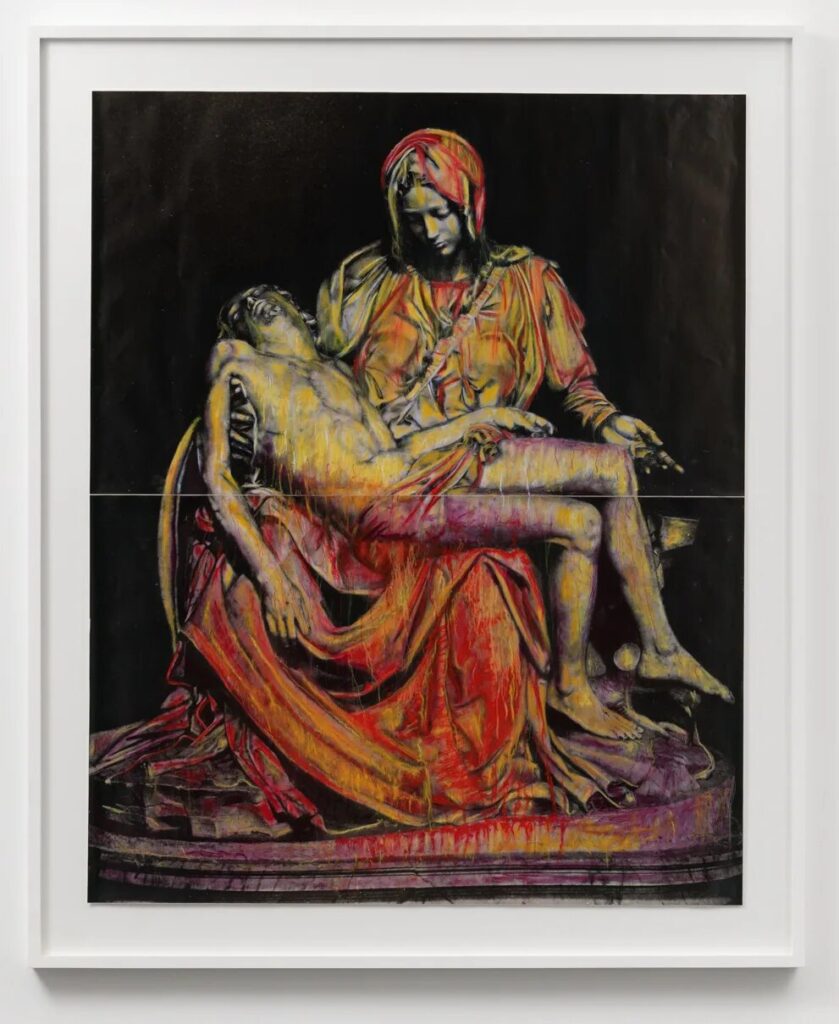

AS: Everything is mixed together in the show, and that, to me, is the way it should be. I like that all the series aren’t in chronological order. They’re all coming from the same place, from the same artist. Even though they’re from different periods, you can play with them any way you want, and it’s more interesting to juxtapose them in unexpected ways. But there’s also a room on the first floor, when you first come in, that has my newest work. More than 30 years ago, I decided to limit my art practice to photography. But last year, I got a book of black and white photographs of Michelangelo’s sculptures. Because the pictures weren’t in colour, I took oil pastels and just started playing with them in a very spontaneous way, drawing on the photos, just having fun. It’s something that I had never done before. I hadn’t used my hands to make a picture since I was a student, and I had never had fun making art like that. So I’ve been doing that a lot in recent months. I’ve been making some huge Michelangelo pieces, drawing on really big photos of the Pieta. And each time it’s a completely different Pieta even though they all start from the same image. Not many people know about this work yet but a few collectors who have seen some of the pictures, they want them. Nathalie Obadia, my gallery in Paris, is going to show them in September. So I’ve been playing with new forms of creation and expression, and it’s fun.

The pastels on the Michelangelos remind me of the Chapman brothers scribbling on a set of Goya’s Disasters of War (1810-20) prints.

It’s not the same. The photos of Michelangelo’s sculptures aren’t the original works of art. They’re black and white photographs so there’s no colour in them. I’m just adding colour on top. I’m not destroying what’s there, I’m inspired by the pictures to turn them into something else, to give them a more contemporary expression while still keeping Michelangelo. I respect what the Chapman brothers did. I like their work, but I can see why some people got upset. I have some conceptual pieces at home and one is a black and white photograph by Man Ray in an old picture frame. The piece I made from it is called Shattered Glass: Portrait of Andree Wildenstein by Man Ray (original 1935). I framed it with the kind of glass that if you hit it with a hammer, it will shatter but won’t come apart. And so I put the shattered glass in front of the picture. You can still see the picture, but it’s become something else. The Man Ray isn’t damaged, in contrast to what the Chapman brothers did to the Goyas. I love those guys but I could never do what they did to Goya, or to any other artist’s work. I’m not that crazy.

Some of your pieces use found objects or historical photos. That leads me to ask, have you curated exhibitions of other people’s artwork?

No, not at all. I would be interested in doing something like that but no one has ever asked.

Christie’s produced a short video about you and your home, which looks almost like a curated exhibition of antique furniture, sculpture and unique objects. On the soundtrack you say that you don’t distinguish your home environment from your artwork. And the collection called The Game: All Things Trump (2018-19) was an installation…

Yeah. It’s in storage. It cost me about $200,000 to produce. Donald Trump should take it to Mar-a-Lago, for himself. It’s a museum to him.

Have you made other pieces that are walk-in collections?

No, but a lot of my money has gone into my home and the things I collect. As a collector, I appreciate other people’s collections. I go and see people’s collections that are very different from mine. I like the fact that people collect with passion and love. It doesn’t have to be what I collect, but sometimes it is. Collecting leads to unexpected places, even to people like Jeffrey Epstein, for instance. I’ve known him for 25 years. I never went to any of his parties. I only had meetings with him.

My Jeffrey Epstein story began in 1995 when a friend, Stuart Pivar, who is a Renaissance/Medieval collector–he was one of the founders, along with Andy Warhol, of the New York Academy of Art–Stuart ran into me on the street and because he knew that I had started collecting works of art, paintings and furniture from the same periods that he had been collecting for decades, he said, “Listen, there’s a guy who just got the Charlie Dent collection.” Charlie Dent was a pilot who became very rich and started this huge collection of Renaissance and mediaeval furniture, works of art and sculptures. He said, you should check it out. He’s up the street in this warehouse. So I go there and I see a bunch of collectors that came for the latest Charlie Dent shipment. Every week, this dealer, Mark, would get a shipment of new pieces from the Charlie Dent estate. And so I saw the pieces but I didn’t really pay attention because there were too many people there. The next day I woke up and I remembered two statues that were there, of the Virgin Mary and Saint John, 16th century wood carvings by a German sculptor. And so I made up my mind that I’m going to buy those statues. I went back to see Mark and one of the statues is missing. Only the Saint John is there. And I say, “Mark, what happened to the Virgin Mary? You didn’t break up the pair, did you?” And he said, “I sold her to a collector by the name of Jeffrey Epstein.” I was horrified. I had lost half the pair. But I felt like one is better than none, so I bought the Saint John immediately.

A year later, I went to Santa Fe for the first SITE Santa Fe exhibition, because I was in it, and I ran into David Ross. He comes up to me and says, “Listen, I told Jeffrey Epstein to go see your show, ‘The Morgue,’ at the Paula Cooper Gallery. And Epstein says, “Why? I don’t want to sell the Madonna.” He had obviously heard that I wanted the Madonna and he thought that’s why David Ross told him to go see my show. I didn’t actually meet Jeffrey until several years later, in 2001. He came to the house and asked me if I needed any money or any support of any kind. I said no, no. We discussed the Virgin, the statue, and he said maybe I’ll think about selling it. Over the years, I had several more meetings with him and then 2006 hit. Jeffrey gets arrested. All this stuff comes out and I’m shocked. This is not the guy I thought I knew. I never saw him with young girls. I never saw any hanky-panky. Yes, I saw girls in their 20s, good looking girls, probably Ukrainian, working for him. I assumed they were assistants or secretaries, whatever. But that’s all I saw. I didn’t know anything about his personal business.

No trips on the private jet to the private island for a private massage.

No trips, no dinners, no parties, only meetings with Irina and me at his big house on 71st street. My last meeting with Jeffrey was in 2016 or 2017 to talk about The Game: All Things Trump, this huge installation that I made with Trump memorabilia. I was looking for space to show it and since he was friends with Abby Rosen and other developers, I thought maybe he could help me find a pop-up space. Nothing came from that meeting, but a few days later, Jeffrey emails me, “Hi, Andres…” That was unusual. He never called me by name and he never used capital letters. It was always lowercase letters. Anyway, the email says, “Hi, Andres. I’m moving things around from house to house. I seem to recall that you want the Virgin. That’s OK with me –for a trade.”

For one of your works?

Yeah. Next day, the Virgin appears at my house, 23 years after I first saw it and 23 years after I tried to get it.

The pair was reunited.

Yeah! Then a week later, Jeffrey emails me. He says: “I want my portrait for the Madonna.” That’s what he decided. And so a few months later, he came to be photographed for his portrait. Three months later, Jeffrey was arrested, and a month after that he was found dead in his cell. That’s how my Jeffrey Epstein portrait came about. When he died, I was in the middle of putting the “Infamous” show together and there was nobody more infamous at that moment than Jeffrey Epstein, so I put him in the show. It was luck. By the way, when we leave Prague, we’re going to Italy.

For a show or just as tourists?

No, we’re hanging out in Italy because I have to be in Rome on the 23rd of June. June 23rd is the 50th anniversary of the inauguration of the Vatican Collection. Fifty years ago, the Pope at that time met with artists and people in the cultural world to introduce the Collection. Now, on the 50th anniversary, the current pope will meet with certain artists and different people. I’ve been invited to meet with the Pope in the Sistine Chapel. I hope I get face time with him. I don’t know how many people will be in a private audience with the Pope, or how close I’ll get to him, but just to be invited! Three days ago, I got a Google alert that a high school in California removed Piss Christ from its curriculum because a bunch of parents complained. In contrast, the Pope has invited me. They’re not stupid: they know exactly who I am. And the fact that I’ve been invited–that is a big deal.

It sure is, and very smart.

Absolutely.

Because I think the public has this image of you as a bad boy and anti-Christian. One of the things I wanted to tell you is that before I saw the Prague show, I only knew that your work was provocative. Scandalous. Now that I’ve seen the show, I know that’s not the half of it. What really knocks me out about your work, and it isn’t talked about enough, is the respect you show for your subjects.

I’m glad you see that.

The combination of reverence and provocation is seamless. It’s like Goya. You are the Goya of this era. I really believe that.

I treat everyone and everything that I portray with reverence. I want viewers to find beauty in my subjects.

All images courtesy of Andres Serrano.

After writing feature articles for Artforum in the 1970s, Robert Horvitz joined Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth publications in 1977 as art editor of their magazines before relocating to Prague in 1991. He has exhibited his drawings at museums and galleries in Europe and the US, including MoMA in New York and Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art.