Class History (1969)

(This originally appeared in the 1969 Yale Banner, p. 294)

Many years ago we lived through what was the best of years, what was the worst of years. It was a year of constant activity; it was a year of dreamlike sojourn in a quadrangle housing three centuries of tradition and not an iota of experience. It was freshman year, a time to discover what Yale was about.

It was supposed to be about education. But you went to an introductory lecture given by a professor who had not talked to an undergraduate for fourteen years and was not about to start now. He mumbled so superbly that you fell asleep and woke knowing it was not just education.

It was supposed to be about tradition. You went to the President’s house and tried to soak up all the history you could find. But while Kingman looked Yale, you and your classmates definitely did not. For weeks even Albertus Magnus girls asked if you were visiting from Lawrenceville.

Some said Yale was supposed to be a time for experimentation. But in those days there was more long hair in your hometown high school orchestra, than in your class. It would be another year before the love generation captured the heart of Mother Yale.

Eventually you stopped worrying about what Yale was and got down to work. You stopped the sink on the fifth floor and flooded the entryway. You watched the first football loss to a Connecticut team in 90 years. You bumped into John Morton Blum in Yale Station and did not understand why everyone in Des Moines was not stunned when you reported your brush with celebrity.

Brash but soon humble you tried to slip into the University life. You found yourself a corner in the community and began the metamorphosis into a Yalie —and the year began to roll by.

Fall was marked immediately by the library’s discovery that Christopher Columbus was an imposter. On Leif Ericson Day, which happened to come just before Columbus Day, Librarian James Tanis revealed a map which proved the Santa Maria had arrived in the New World a few years too late. There are a great many Americans of Italian descent and they were none of them overwhelmed by Yale’s map. The director of one Italian historical society spoke for his countrymen: “Anyone can make a map,” he said. “How do you know these guys (at Yale) know what they are talking about? I’ve never heard of any of them.” And a member of the Knights of Columbus turned to ad hominem: “Up at Yale,” he said, “ they’re too radical and too drunk and I know.”

You, the freshman, were beginning to discover that he might be right. Yale was rather radical and from time to time rather drunk. But up at Yale even these qualities were present always in moderation. More than 2000 Yalies did sign a full-page ad in the Times protesting the Vietnam War. And another 50 refounded an SDS chapter. But, on the other hand, another 1,000 students rallied to protest civil disobedience as a form of war protest.

Vietnam remained a muddled issue for many months. Staughton Lynd went to Hanoi, returned, had passport problems, did a great deal of speaking, but could convince only some that he was right. The university had alumni problems, the students did a great deal of listening, a few hundred marched for peace in Washington, one fasted in Pierson. But still it was not until the end of the year that in your class the majority finally decided we had no business in Vietnam.

Freshman year offered less serious lessons as well. For instance, you learned that everyone at Yale had to be photographed in the nude. Then you learned that everyone important in the world had been photographed in the nude because they were all, apparently Yalies. In New York, at any rate, it was clear that only Yalies were allowed to be elected Mayor. And if New Haven’s Dick Lee, also running again, was not a graduate, he had at least worked for the University.

You learned too that nude or clothed it was difficult to get a date. Perhaps you turned to Operation Match and had a computer fix you up. One freshman was given the names of ten boys. “I may be desperate but this is ridiculous,” he said.

Eventually you and he passed out of desperation, through the ridiculous, and into what at Yale passed for the sublime. The managing editor of the News defeated the female managing editor of the Crimson in jacks: it was silly but was really sublime enough to be cool. You caught on to this cool quickly. If you didn’t have a date to see the Ronnettes at the Prom, you went to New York, maybe to look for a certain hotel clock under which some girls were supposed to be. Or if you had nothing to do one spring day you were sharp enough to casually lounge on your windowsill long enough for the cameras to immortalize you in “To Be A Man.”

As you acquired the trappings of Yaleness, the issues that would dominate your four years began to come into focus. In the spring coeducation was well-discussed, though not a single freshman could know yet that he was in the last Yale class never to go to school with women. Distributionals were abolished— though many freshmen did not realize they would spend their senior year still trying to escape Astro or Forestry or Latin. Nine upperclassmen won permission to move into New Haven slums. No one realized then that the same slums would be the scene of riot in little more than a year. And in May there was the draft deferment test—the test would eventually mean nothing but the draft would in the end mean somewhat more.

But these issues were in the future. Freshman year they and you only had time to find a foothold in the Yale community. And by spring, when you had secured your place, you had realized what Yale was about. It was about practically everything. And the whole panoply—the ridiculous and the sublime, the simple and the difficult, the ambiguous and the straightforward—all the elements were in your grasp and you had become a real Yale man. Then the trees blossomed, bands appeared on the cross-campus, you passed your finals, and you went home.

You returned to become a sophomore, which is a word derived from the Greek meaning both wise and foolish. There were to be many foolish things done by you that year but the wisest was taking Margaret Mead’s course. Miss Mead attracted the largest and, judging by the grades, the hardest working class of any teacher in the college. Fortunate it was, too, that her views on scholastic endeavor coincided with yours: no reading, no notetaking, and fair grading.

It was not easy of course for Miss Mead to match your standards, for you had developed a clear concept of what it meant to go to Yale. You were after all in a college; you had changed your major twice; you had the grading system psyched out; you were experienced in both watching football and taking road trips. You had, in short, staked out your own fiefdom in the feudal universe of Yale.

It was not an easy process for there were always many new elements to incorporate in your incipient world view. There were, for instance, countless varieties of the cinematic experience to view. The Lawrence featured an analytical probing along Joycean lines into the conscious and subconscious female life —they called it “I, A Woman.” And at 100 Art Gallery there were certain Japanese films which accidentally attracted a mob of 1000 due to some lurid sensationalist Yale Daily News publicity.

But such lapses of taste were part of the sophomore experience. And so too were other lapses, such as the Rutgers game and a blocked punt with another New Jersey team. Some would be discouraged and abandon the cause. A political science professor named Deutsch followed the team up to Harvard and decided to stay with the winner. Back home, Prexy’s put away their educated hamburger and closed down. Gene Rostow put away his education for a while too and went to the State Department.

Others dropped out in different fashions. Kingman Brewster was advocating a year off between high school and college. But as Michael Kahn explained, as various panels and forums discussed, and as the New Haven Police Department eventually discovered, there were ways to take time off without bothering to leave at all.

Dropping out could have become more popular but for constant reminders that the world outside was quite a hassle. The ominous extent of the war effort, for instance, was well indicated when Special Assistant to the President Sam Chauncey was called up for a physical. “First Deutsch and now this,” President Brewster said when he learned the squash star was in excellent condition.

You knew times were bad when they had to call William Buckley up to debate Bill Coffin. But Yale’s greatest actor was upstaged by another graduate: Paul Mellon pulled a grandstand play and gave Chapel Street an art gallery, to the not unmixed delight of local merchants.

Then over Christmas came promise of an even grander gift: Vassar. We all spent the spring in delirious rapture at the prospect of things to come. The Grand Refusal was not to come until the fall. Meanwhile students felt they owed the university and the world something in return. The News consequently advocated the legalization of marijuana. And Congressional candidate Bob Cook’s sociology class placated the registrar’s office by voting themselves 100s for the course. Other students cinched their belts and demanded four courses instead of five. The bursary boys humbly threatened to strike and then finally allowed themselves to accept a raise. By the end of the spring even the faculty had started a self-strengthening movement. They voted to ask for the abolition of 2-S deferments.

The question of the war and the draft grew more and more important during the year. A Day of Inquiry into the subject in May primarily showed how enormous was university opposition to Lyndon Johnson’s policies. And the next year that opposition would only grow larger and more violent.

But that was the next year. If draft protest was to increase, marijuana use was already up to at least 25 percent of students, according to several polls. Some students were even switching to banana peels for their

mystic pipes. Also up after 4 million sales was the price of Yankee Doodle burgers—from a quarter to 30 cents. And going down, as the year came to a close, were Winchester and North Sheffield Halls. Rumors that Vince Scully would not let the bulldozers pass proved false. By the fall only a few bricks were left of noble, dusty, and drafty Winchester.

Sophomore year obviously was full of rises and falls. Junior year was an intensification of the same, until by the middle of the year you realized that, despite the fluctuations, you were at the locus of all University activities.

News Sports Editor Phil Hersh commenced ’67-’68 with the announcement that it was to be THE year for Yale sports. Whereupon the starting quarterback fractured his wrist, the coat and tie rule was abolished, SDS was refounded, Phi Gam folded, and Erich Segal left to write “Yellow Submarine.” Although Hersh would eventually be right, it was clearly to be THE year for a great many other activities.

The most important of these, the war protest, gained strength rapidly. In October several hundred students gathered to stand in vigil while Lady Bird Johnson ate a Political Union dinner inside Commons. Others joined the Oct. 21 march on the Pentagon. And later 300 students would announce they wouldn’t go into the army.

It was good that there were easier things to do that fall. For instance—allowing the faculty to drop numerical grading. It was a relief to forget those numbers. And it was a delight to remember others. For instance one weekend the number was 56-15 and later a significant number was 29-7. Even going to New Jersey was worth bringing back that number. Especially since we certainly needed an ego booster—only two days after the Princeton win Vassar announced she wouldn’t go either. We were left, apparently, to be entertained only by our sad, few graduate students, our many sad mixers, a phantom foot nibbler in the stacks, and stories about a hot iron brand in one of the more physical fraternities.

It might have been depressing but for a great afternoon in the Bowl. The Cambridge team was more than adequate. But our Ohio Quarterback threw an incredible pass to an Ohio end and then an Ohio monster back recovered a fumble. 24-20 for the Ivy League Champions.

Then came winter and Hollywood sent us The Graduate, which psyched out many who thought they were viewing their autobiographies. Whereupon the faculty reduced the course load and our minds were further deranged. Looking for responsibility, commitment, and something to do now that we had no grades or courses, we found Gene McCarthy. Then we found Bobby Kennedy. And then we lost Lyndon Johnson. For a few days the future was ours. A gunshot in Memphis in April ended that illusion. And two months later, shots in Los Angeles would destroy still more dreams.

The world was a great deal with us that spring. Columbia revolted and that hardly surprised anyone. You either accepted it or put it out of your mind or both.

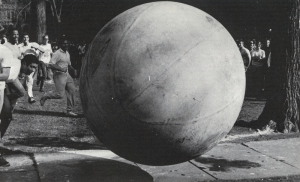

For a time it seemed that nothing could grip the college anymore. Even a university employee strike generated little student response. Finally, however, we found an issue petty enough to be popular: the Cross Campus controversy. We wanted to play football instead of study underground. We won and they lost. It was student power laced with strong doses of humor, triviality, and the exuberance that every spring brings to New Haven. We needed such an issue that spring and that year, because we were becoming very committed very quickly, and it was very tiring.

Hubert Humphrey, Richard Nixon, and August in

Chicago did not cure our anxieties, erase our weariness, or satisfy our need for involvement. But if ever there was a time to soothe such frustration it was senior year at Yale.

George Santayana, writing from his chair in the Harvard philosophy department at the turn of the century, described Yale in this fashion:

Yale has a religion. The solution of the greatest problems is not sought, it is regarded as already discovered . . . The essential object of the institution is still to educate rather than to instruct, to be a mother (therefore) of men rather than a school of doctors. In this Yale has been true to the English tradition, and is, in fact, to America what Oxford and Cambridge are to England, a place where the tradition of national character is maintained, together with a traditional learning. The Yale principle is the English principle and the only right one.

By senior year we all came to believe, in our particular ways, in the Yale religion. We had gone into our individual activities, studied our separate subjects, and emerged into the final year with the feeling that the community subsumed, if not transcended, our personal worlds. Before and after being jocks, or Newsies, or Whiffs, or frat men, we were Yale men. We had faith in this: it was our lux and our veritas. And in the fall at least the football game was where we celebrated this strange religious belief, this mystic and inevitable bonding forged between us and the Mother of Men. We had, of course, the team of teams. Twenty-nine seniors led it from victory to victory, each greater than the one before.

So much strength filled the Bowl, in fact, that it overflowed to inspire the onlookers. One senior, exhilarated after a victory, took it in his own hands to do the impossible, to eliminate the much-maligned but time-honored road trip. He called his effort Coeducation Week. Then to top that he staged in his college a miniature Columbia over the female housing issue. When the papers were reshuffled and the announcements reannounced it was really true that the Mother was to have more than Men to raise in the future.

But if Avi Soifer spent a lot of time worrying about girls, that did not mean others were not engaged in more serious endeavor. Many spent a few days in the streets with the Living Theater. Others transferred their radical act to Long Island and helped elect Al Lowenstein to Congress. And still others concentrated on law boards, OCS exams, the Abe Fortas Film Festival, and other senior year diversions.

But everyone together followed the team. One grand day was November 16 when a Princeton eleven was demolished. Unforgettable was November 22 when a News squad crushed a Harvard Crimson contingent on the G.E. College Bowl. And finally came November 23 at Cambridge. Of that it can only be said that no self-respecting religion can subsist on lux and veritas alone; it must include the bizarre, the fated, and the tragic as well. Our understanding of the Yale religion comprehended these qualities well after that afternoon in Cambridge.

Our pride was immediately resurrected of course when we learned that President Brewster had been named Secretary of State. “First 29-29 and now this,” Sam Chauncey mumbled. Then we learned Brewster was not Secretary of State. If Nixon did not want our President, did this mean we were, as had been charged all fall, merely a football factory and not the source of the nation’s leaders? The possibility loomed more real when the pros drafted three ex-Varsity players.

But the university corrected its image immediately by dropping ROTC from its credit ratings. A blizzard of mail from alumni protesting our newly radicalized image was followed by a blizzard of snow from the sky, and we slipped into a winter’s nap of senior complacency, random speculation about a non-football draft, and countless hours of rumination about how fine it had been to be at Yale and how much worse off everyone else was.

And wasn’t that the truth? Sarah Lawrence and a small New Jersey men’s school copied our coed week. Trinity, Vassar and the same small New Jersey school were desperately planning for coeducation while Inky Clark was already checking our incoming coeds. And even Harvard was trying to catch up. They wanted to get closer to Radcliffe, though no one knows exactly why.

Like Old Blues we scoffed at the laggard institutions and like Old Blues we beamed at our swim team’s victory over Stanford and our hockey team’s win over Harvard. Like Old Blues we slipped through the spring and it was over.

Santayana said he saw at Yale a “fullhearted wholeness, (an) apparently perfect adjustment between man and his environment, (a) buoyant faith in one’s divine mission to be rich and happy. No wonder,” he said, “that all America loves Yale, where American traditions are vigorous, American instincts are unchecked, and young men are trained and made eager for the keen struggles of American life.”

That was 70 years ago. It is no longer certain that everyone here is perfectly adjusted, or buoyantly eager to be rich and happy, or even completely willing to be loved by America. But nonetheless Santayana’s observation still holds true. For some reason everyone loves Yale. We may have thought four years ago that we would be different. But we were wrong. Bring in the cliches and bring out the handkerchiefs; criticize what you will but admit it’s true that in senior year.

The saddest tale we have to tell

Is when we bid old Yale farewell

Fol de rol de rol rol rol.

REED HUNDT