Class Notes – Mar/Apr 2020

Jim Grew writes: “I was inducted into the International Waterski & Wakeboard Hall of Fame this year, the International Governing Body of all Towed Water Sports recognized by the IOC to go along with my 2013 induction into the U.S. Water Ski & Wake Sports Hall of Fame, the national governing body recognized by the USOPC.” Related story.

Jim Grew writes: “I was inducted into the International Waterski & Wakeboard Hall of Fame this year, the International Governing Body of all Towed Water Sports recognized by the IOC to go along with my 2013 induction into the U.S. Water Ski & Wake Sports Hall of Fame, the national governing body recognized by the USOPC.” Related story.

Mike Schonbrun (mks@balfourcare.com): “Loved seeing everyone at the 50th. My appreciation for Yale gets stronger every year, and the three days in May cemented that feeling. While still rooted in Boulder, Colorado, my senior housing company Balfour, is expanding to the east- Georgetown in Washington DC and Brookline in Massachusetts. Would love to get reconnected to classmates in those areas.”

Howard Newman, co-founder of private equity firm Pine Brook, has received the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Oil & Gas Council for his contributions and innovations in energy investment. Related story.

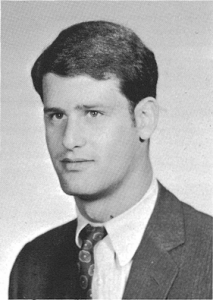

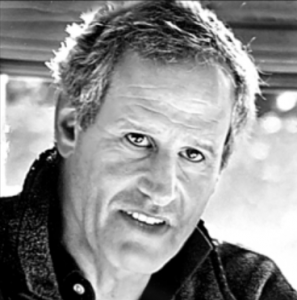

John P. Meyer passed away in December, 2019. His good friend Bill Newman has written the definitive memorial: “John was afflicted with frontal lobe dementia which shortened his life. He was married to JoFrances Meyer, a person of extraordinary kindness and compassion, who misses him deeply. He is survived by his three children, Jessica, Sebastian and Amelia, from his prior marriage to Joanna Anderson, and by his step-daughters Elizabeth and Jacqueline. JoFrances cared for John with all of her abundant heart and soul through his devastating illness.

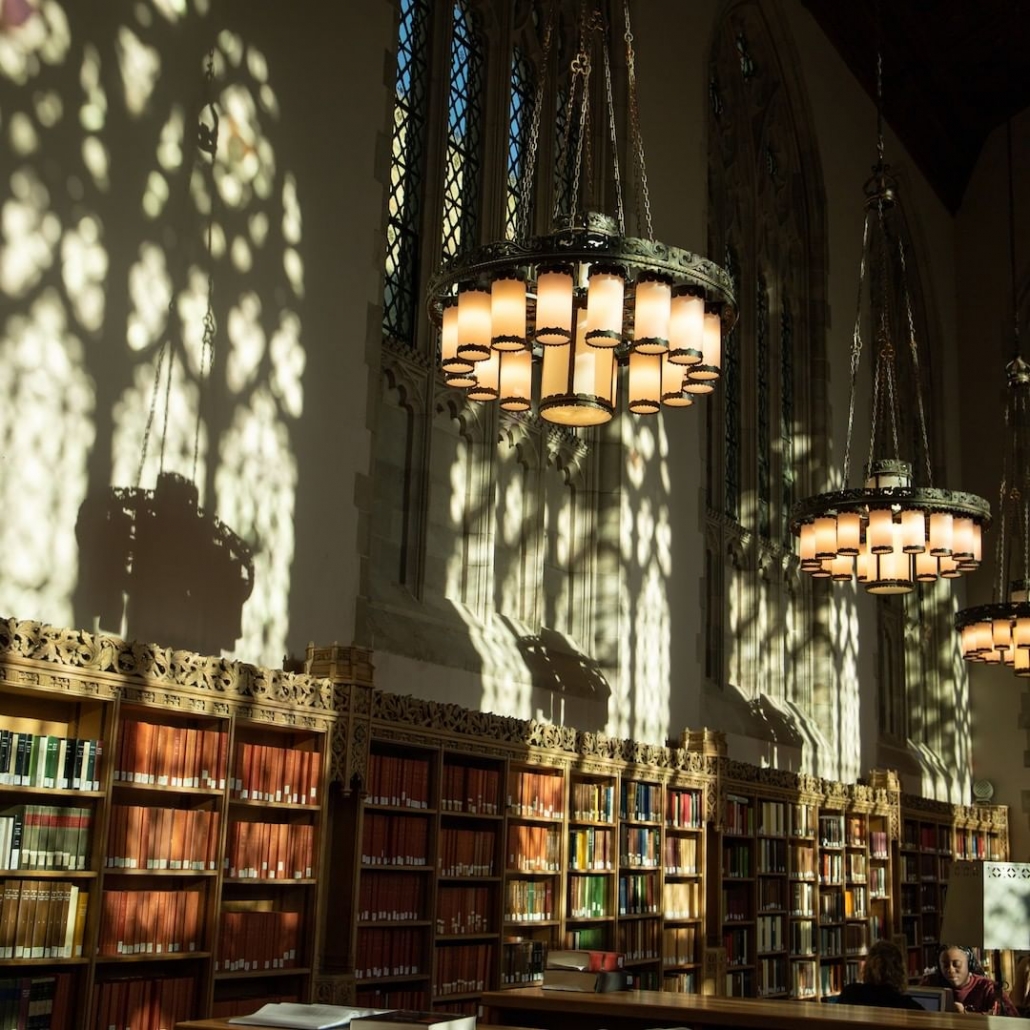

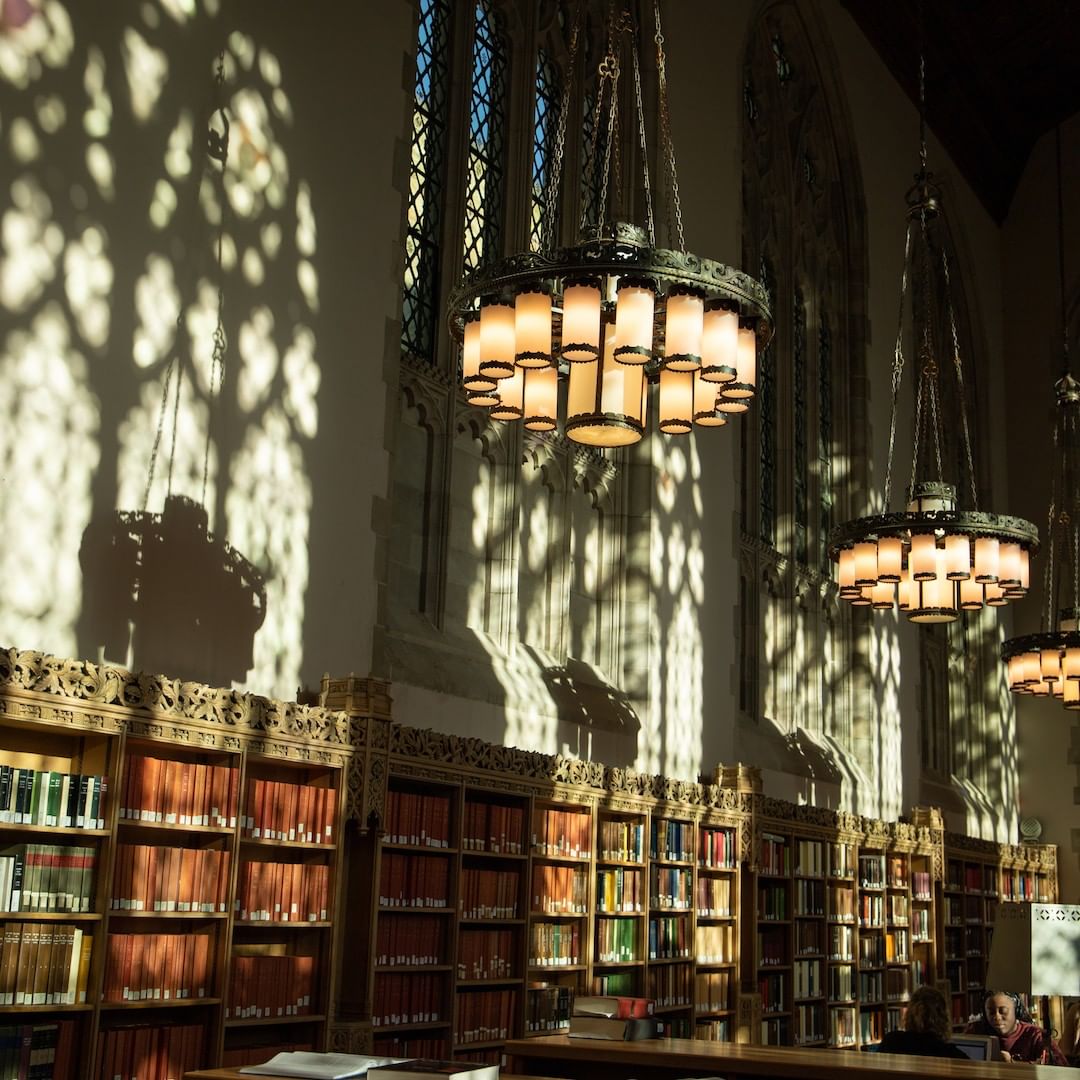

John and I met early on in our freshman year. By the end of that school year we had become close friends. We remained close both while at Yale and for decades afterward. There was no more gracious, noble and thoughtful classmate than John. We were fellow majors in History of Art. We took Vincent Scully’s HA10 together and were immediately hooked. He knew that he wanted to be an architect, so the major was almost a given for him. John came to it, almost by genetics. His mother was a sculptor and exhibited her works in prominent New York City galleries. She was one of the founders of the Whitney Museum of American Art. His father was a literary agent, employed by Viking Press. Art and books were nightly dinner table topics. John opened a door to life’s glowing possibilities to me. He also coached me through and introduced me to the inhabitants of the world through that door, with his beaming smile and his blazing eyes. His manners were impeccable, his soul irresistible.

History of art became our commons lens on the world. We traveled to Europe together in the Summer of 1968. In Paris, we ran around the streets dodging the police and their tear gas canisters when we decided to join the 1968 Revolution. We went to the singularly famous Abbey Church of Saint Denis to meet one of our History of Art professors and received a tour on our hands and knees of the basement crypt, replete with the skulls of those who had died over the last nine centuries. We met up later in Venice and together toured the churches, museums and canals, relating what we saw before us to the lantern slides that glowed back on the screens in Street Hall.

By our senior year, our common interests expanded to city planning. We took Alex Garvin’s city planning seminar together, which used New York City as its laboratory. As the winter of 1969 approached, however, we no longer could avoid the horribly painful question of how to confront the Vietnam draft. John read, and re-read Dangling Man, Saul Bellow’s apprentice novel set in 1944 about a man whose life has stalled while he waits to be inducted into the Army. He became depressed at the prospect of being sent to Vietnam and was convinced that he would die there. On graduating, he was able to join Vista and went off to serve on a Native American reservation in northern Nevada. He was happy there. After Vista, he attended the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation at Columbia. After graduation, he worked for a series of architecture firms until he set up his own, Meyer & Gifford Architects. He did a good deal of work for schools in the New York City area, including the Brearley School on the Upper East Side.

When I received word of John’s passing, I walked over to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In the contemporary art section, in the rear of the first floor of the museum, well past the interior rooms filled with 16th and 17th Century furniture, are the foremost examples of 20th Century American Art, starting with the years when American art exploded into view. Hanging in the midst, flanked by other masterpieces on either side, was the gray and beige painting of a water plant’s massive system of pipes and towers created by the American precisionist artist Charles Sheeler in 1945. I recalled that Sheeler’s painting was the subject of John’s senior thesis, read by Professor Jules Prown. John camped here, before this very work of art, next to where I was standing, for hours in 1969 as he thought and re-thought what to write in his thesis. He admired the straight lines, the shadings, the architecture-drawing like quality of the finished work. He reveled in the composition and clarity of the picture. He was writing his notes in his notebook with that amazing, clear handwriting of his, with crisp lines and hard angles, capturing what he was seeing in words so that he could inform the rest of us. This was his place in his museum in his city and for at least a few minutes more we reverently stood together, very close. A guy could not be more fortunate than to have John Meyer as a friend.”

When I received word of John’s passing, I walked over to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In the contemporary art section, in the rear of the first floor of the museum, well past the interior rooms filled with 16th and 17th Century furniture, are the foremost examples of 20th Century American Art, starting with the years when American art exploded into view. Hanging in the midst, flanked by other masterpieces on either side, was the gray and beige painting of a water plant’s massive system of pipes and towers created by the American precisionist artist Charles Sheeler in 1945. I recalled that Sheeler’s painting was the subject of John’s senior thesis, read by Professor Jules Prown. John camped here, before this very work of art, next to where I was standing, for hours in 1969 as he thought and re-thought what to write in his thesis. He admired the straight lines, the shadings, the architecture-drawing like quality of the finished work. He reveled in the composition and clarity of the picture. He was writing his notes in his notebook with that amazing, clear handwriting of his, with crisp lines and hard angles, capturing what he was seeing in words so that he could inform the rest of us. This was his place in his museum in his city and for at least a few minutes more we reverently stood together, very close. A guy could not be more fortunate than to have John Meyer as a friend.”

“All beauty and art evoke harmonies that transport us to a place where, for only seconds, time stops and we are one with the world. It is the best life has to offer.”

—André Aciman