Douglas P. Woodlock – 50th Reunion Essay

Douglas P. Woodlock

1 Courthouse Way, Suite 4110

1 Courthouse Way, Suite 4110

Boston, Massachusetts 02210

d_woodlock@mad.uscourts.gov

617-748-9293

Spouse(s): Patricia Powers Woodlock (1969)

Child(ren): Pamela Egleston (1976), Benjamin Woodlock, (1979)

Grandchild(ren): Anne Egleston,

Education: Yale, BA 1969; Georgetown, JD 1975

Career: US District Judge (Boston), 1986–present; Private law practice, Goodwin, Procter & Hoar (Boston), 1983–1986 and 1976–1979; Assistant US Attorney (Boston), 1979–1983; Staff, Securities and Exchange Commission (Washington, DC), 1973–1975; Newspaper reporter, Chicago Sun–Times (Chicago and Washington, DC), 1969–1973

Avocations: Architecture, Reading, Travel, Skiing

College: Ezra Stiles

Twenty-five years ago, I reported that I had found in the summer of 1969 “a permanent compass when I married Patty Powers, who had been throughout college (and remains today) the still point in my turning world.” The first quarter century thereafter, I concluded, had “largely been a process of working out the details.” Nothing in my personal trajectory during the subsequent quarter century has disturbed that conclusion.

However, resuming a report of personal details, which I recited at length in my submission for the “Twenty-Fifth Reunion Class Book,” seems less significant as something for me now to offer classmates. Rather, what fundamentally concerns me at this point is the sense that our shared national trajectory from the end of the ’60s, a period that Richard Rovere accurately characterized as a “slum of a decade,” has returned us 50 years later to the same place.

Rovere described that place as one of “steadily declining civility and mounting instability” where separate camps “think in slogans and communicate in invective.” Alexander Bickel, who presided in the dining hall as a Fellow of Ezra Stiles during my residence there, worried then we were in danger of becoming a society which might “succumb to or be seized by a dictatorship of the self-righteous” which he thought was “inevitably the conclusion to which disenchanted and embittered simplifiers and moralizers must come.”

Napoleon is said to have observed that “to understand the man you have to know what was happening in the world when he was 20.” What was happening around us when we were 20 seems to be happening again now. The underlying fissures in our diverse society have again broken open with volcanic force fueled by class conflict and accelerated by the continued challenges of racial struggle. The disenchanted and embittered have sought to cast every distinction as one of moral failure or unfulfilled obligation and have made what could be common ground a no man’s land.

As difficult as this return to an openly riven society has been, I don’t believe it necessarily represents the conclusion Alexander Bickel feared. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s husband was wont to say that the true symbol of the United States is not the bald eagle but the pendulum. I am reasonably hopeful the current swing of the pendulum back to where it was when we graduated will be countered in the not too distant future by movement in the opposite direction. That recalibration, I hope, will be facilitated by resurgence of what Judge Learned Hand called the “Spirit of Moderation”: “the temper which does not press a partisan advantage to its bitter end, which can understand and will respect the other side, which feels a unity between all citizens… which recognizes their common fate and their common aspirations.”

I am acutely aware that I speak from a position of what is now disparagingly called privilege. With more than a measure of good fortune, since graduation I have benefited from a half century of stability in a comfortable and rewarding domestic and vocational life. I share a marriage that becomes more meaningful every day and is further enriched by our children and their spouses and a grandchild who seem well and happily launched. I can continue in a stimulating job that I am able to hold as long as I choose, whose purpose demands of me daily to do what I can to secure societal civility.

Of course, I was particularly privileged to have been 20 at Yale, where in addition to being buffeted by the larger turbulent world around me, I was introduced to habits of personal reflection that have caused me to return again and again to study of classics in literature to which I was rigorously introduced. It was then I first began to grapple meaningfully with T.S. Eliot’s “Four Quartets,” from which I drew my earlier and enduring description of Patty as “the still point in my turning world” and which reminds me at this stage in my life that

Old men ought to be explorers

Here and there does not matter

We must be still and still moving

Into another intensity…

In my end is my beginning.

Douglas Woodlock

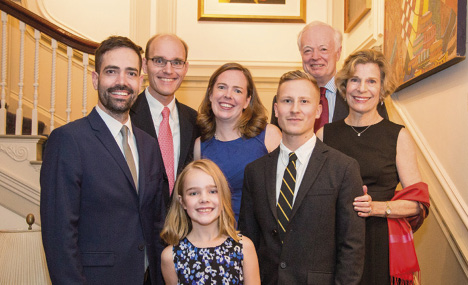

Woodlock Family

If the above is blank, no 50th reunion essay was submitted.