Dennis Drogseth (SY) Interviews Architect of Yale’s New Colleges

Dennis Drogseth (SY ’69) recently interviewed Melissa DelVecchio (Yale, M.Arch 1998), the partner in the architectural firm that designed Yale’s two newest residential colleges.

He sought, and got, an inside look into some of the personal and professional challenges in creating two new colleges. The last time that happened was Eero Saarinen’s Morse and Stiles colleges in 1961.

Drogseth, a technical analyst and author, is not an architect, but he admits he inherited a love for it from his architect-grandfather, Eistein Olaf Drogseth, a Norweigan immigrant at the turn of the 20th century.

Watch a slideshow of the new colleges

Start Slideshow

The interview was arranged and published by the Yale Club of New Hampshire. Preparing for the interview, Drogseth read up on the new colleges (see The New Residential Colleges at Yale: A Conversation Across Time) and checked out DelVecchio’s impressive resume.

Drogseth concluded “If you think that the past is always mere prologue, it’s time to think again. Yale’s new Benjamin Franklin and Pauli Murray Residential Colleges were inspired by both a strong sense of history and an equally strong awareness of the present.”

Here is the interview, as published:

Interview with Melissa DelVecchio, Project Design Partner with Robert Stern Architects

Partner, Robert A.M. Stern Architects

Melissa DelVecchio played a leading role in the planning and design of Yale’s new Benjamin Franklin and Pauli Murray Residential Colleges. Ms. DelVecchio has also led architectural projects as geographically far-reaching as the Schwarzman College at Tsinghua University in Beijing, and a crowd-sourcing effort to digitally recreate Sir John Soane’s Bank of England. Domestically, she has managed many projects, with a focus on those associated with university campuses.

Ms. DelVecchio received her Bachelor of Architecture degree from the University of Notre Dame, and her Master of Architecture degree from Yale.

You got your M. Arch at Yale—do you have any standout memories you’d like to share?

When I think about my time in graduate school relative to my subsequent work on the colleges, two stories come to mind. My first employer, Scott Merrill, whose office is in Florida, was a Yale School of Architecture alumnus. And when I was accepted at Yale while working in his office, he was very excited. He encouraged me to immerse myself in the architecture of the Yale campus, especially the colleges designed by James Gamble Rogers. And with that in mind, he arranged a gift for me — a meal plan to eat lunch or dinner at each of the residential colleges. He provided me with a set of very special, handwritten cards allowing for one meal at each college, to ensure I would visit every one. It was a very sweet and special gift.

The other thing that came to mind was an assignment from my studio professor Thomas Beeby, who had been the School’s Dean earlier. Beeby assigned a studio project that was the subject of a major competition that was then under way for a new student center at the Illinois Institute of Technology, which Rem Koolhaas later won. Looking back I see now that my student design foreshadowed in some ways the work we did for the Benjamin Franklin and Pauli Murray residential colleges.

The beauty of Mies’s design for the IIT campus was that it was a loose arrangement of buildings originally built in a very dense urban context—but as the neighborhood declined, that dense urban context had been demolished. There was no longer any “there” there. My response was to fill the entire two-block site adjacent to the campus, breaking up the student center program and combining it with housing, essentially proposing two residential colleges to create urban density. As it turned out Rem Koolhaas’s competition-winning scheme, although very different, had a similar approach, filling up the block to extend the neighborhood.

Could you describe your role as project design partner in the Ben Franklin and Pauli Murray Colleges more specifically—how did you work with Robert Stern and the broader team?

The process [at Robert A.M. Stern Architects] is very collaborative and team-oriented. It’s a little bit like school, where you work on your own studio project, and then review your work with your professor. Here, we develop ideas that go through an iterative review process with Robert Stern. This process applies to all aspects of a project—site planning, building massing, design of individual rooms, etc. I worked with the 30-person team to develop and organize the materials we should present to Bob Stern in this iterative process. Over the nine years we worked on the project, more than 140 employees worked on the Benjamin Franklin and Pauli Murray residential colleges.

What led you to decide to move to ‘Collegiate Gothic’ in the style of Branford and Saybrook colleges, for example?

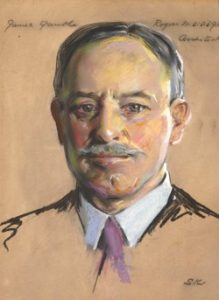

Yale had already made a decision that these colleges should be traditional. Either Georgian or Gothic. Bob Stern felt that Gothic was the better link given its history at Yale and his admiration for the work of James Gamble Rogers, who designed Branford and Saybrook, as well as other buildings at Yale, early in the last century. Gothic was also the predominant style of the buildings on Science Hill.

The overarching reason for choosing Collegiate Gothic was that the site was considered to be far away from the main campus. As such it just didn’t feel like a part of Yale. And in fact, the setting by the cemetery and surrounding buildings made it feel further away than it was. To a large degree our intention in choosing Collegiate Gothic was to collapse the impression of distance.

Part of the job was, to “channel” James Gamble Rogers, as I understand it. What came through the most in that experience?

As we reviewed Rogers’ work, we continued to see things that I hadn’t seen before. In a sense he continued to teach us all throughout the design process. At each level of design, we delved into what he was thinking and doing in his work. In terms of building massing, we learned that his buildings, though they seem infinitely varied, had very simple, rational plans behind them. When analyzing details later, we noticed that Rogers was very strategic in his deployment and variation of details within a courtyard or across a facade. We also looked at his original drawings and discovered that Rogers didn’t have to draw nearly as many drawings as we did. Modern architects have to do a lot more fleshing out. We also have to accommodate a lot of functional capabilities that weren’t available a hundred years ago.

What was the biggest challenge you encountered in the project?

I think the biggest challenge for us was trying to adapt to using Revit 3-D building information modeling software. The software was designed to work best on repetitive, vertical buildings without the variety in Benjamin Franklin and Pauli Murray residential colleges. But we found the support we needed to make it work for us. We also supplemented it with Digital Project, which is more accommodating to Gothic design.

You’ve had a long track record of achievements along with several significant international experiences. How did the Yale project stand out for you personally?

On a very personal level, not only did I go to school at Yale, but I grew up about 15 minutes away in Stratford. The architecture at Yale was my first exposure as a child to urbanism, and to great architecture and fine buildings. I would ask my parents to drive me to New Haven to explore these buildings. It meant a lot to me to be able to add something so substantial to the urban environment that inspired me as I grew up.

On a somewhat less personal note, it was significant to be able to write a book—a chance to document how much scholarly work went into the project, to look in depth at both the people and the process.