The Beatles: Get Back—an Experience or a Memory?

It’s the holidays and once again I’m arguing with classmates and friends about the latest Beatles’ release! Plus ça change. This time, it’s about Peter Jackson’s sprawling but captivating, 8-hour miniseries on Disney+, documenting the Fab Fours’ creation of the Let It Be album, including the rooftop concert that would become their last.

Back in our school days, The Beatles seemed to dominate our Decembers, beginning in freshman year when Rubber Soul could be heard blasting out of every entryway on the Old Campus. “Isn’t it good, Norwegian Wood?” Two years later we had Magical Mystery Tour and in senior year we had The White Album. “Back in the USSR,” baby. No wonder I think of a snowy New Haven when I think of The Beatles.

This time there was a five-decade gap between the previous and the latest Beatles’ holiday release, but no matter. We Beatlephiles are a patient bunch. It was welcome news when Lord of the Rings director Peter Jackson volunteered to open the Beatles’ vault and comb through 55 hours of film and 120 hours of sound recordings from 18 days in January, 1969, as the band rehearsed for an album and live concert. Their hour-to-hour work and chatter—ruminating, gossiping, joking, teasing, venting—was all there for Jackson to happily cherry pick. The result is The Beatles: Get Back, a documentary now streaming on Disney+ (for a mere $8 a month).

A small portion of this audio and video appeared in the Let It Be film that was released in May, 1970. (51 years goes by pretty quickly, doesn’t it?) But that documentary was a sanitized 80 minutes. This one is an untidy 468 minutes, including hours of conversing, songwriting, arranging, jamming—plus the entire rooftop concert at Apple Corps headquarters that disrupted central London for 42 minutes.

Some less-than-fanatic viewers have complained that the doc could have used heavy editing. I’d have to agree, though when I found myself wanting to fast forward, the band at that moment would usually begin work on a song fragment that was instantly recognizable as another Beatles’ classic-in-the-making—e.g., “Get Back,” “Let It Be,” “Across the Universe,” “The Long and Winding Road.”

But the big surprise from this documentary, as you may have heard, is these boys were actually having fun together. They were not a miserable bunch of grumps, despite their own characterizations of this period later. Now some dissension did surface. George Harrison—having been marginalized by John Lennon and Paul McCartney for years but now feeling validated after playing with Dylan and The Band in Woodstock—chafes at Paul’s micromanagement of his playing. “I won’t play at all if you don’t want me to play.” He finally walks out on January 10. Later John tells Paul how they might deal with it. “I think if George doesn’t come back by Monday or Tuesday we ask Eric Clapton to play.”

But George’s departure is temporary and he returns with a more optimistic attitude. The Beatles move their rehearsals from the cold and cavernous Twickenham Film Studios to their new Apple Studios, which enhances their mood considerably. When old friend and keyboardist Billy Preston drops by at George’s invitation, they immediately put him to work for the remaining rehearsals. The band moves into an even higher gear as a five-piece unit.

Yet, to my ears, from the beginning of January the band was already playing better in the studio than they had in the past. (They had stopped touring almost two and a half years earlier.) Though Paul had long been a consummate musician, his bandmates—especially George, but also Ringo and John—were finally coming into their own as skilled players and were better able to enhance each other’s musical ideas. They were developing songs together (though in fits and starts) in ways they weren’t capable of previously. They were approaching a creative peak, according to some critics, that they eventually reached in the Abbey Road sessions in the months that followed.

Yet, to my ears, from the beginning of January the band was already playing better in the studio than they had in the past. (They had stopped touring almost two and a half years earlier.) Though Paul had long been a consummate musician, his bandmates—especially George, but also Ringo and John—were finally coming into their own as skilled players and were better able to enhance each other’s musical ideas. They were developing songs together (though in fits and starts) in ways they weren’t capable of previously. They were approaching a creative peak, according to some critics, that they eventually reached in the Abbey Road sessions in the months that followed.

The perception of the curmudgeonly Beatles in perpetual conflict before and during the Get Back sessions was created in part by the acrimonious breakup of the band 15 months later. That’s when they found themselves in times of trouble. The Let It Be album and documentary were released within a month of Paul suddenly announcing his departure from the band in April 1970. The depressing breakup narrative seemed to permeate that album and film, accompanied by discouraging statements by band members at the time. It wasn’t helped by John, George, and Ringo’s embrace of the unscrupulous Allen Klein as the Beatles’ new manager. Or by Klein asking producer Phil Spector to finish off the Let It Be album. Both moves served to alienate Paul—and in retrospect he was right to resist. (Klein was eventually sued by the remaining Beatles and Spector’s syrupy production of the Let It Be tracks was considered an artistic disaster by critics.) The band WAS a mess by spring 1970.

To make sense of the disconnect between the mostly joyful creativity on display in the Get Back documentary and the dismal recollections of it by The Beatles themselves, we can turn to Daniel Kahneman, Princeton’s acclaimed cognitive psychologist. Kahneman is famous for drawing a distinction between the experiencing self, who is aware of only the present moment, and the remembering self, whose memory of an event can be much different, based on an after-the-fact story constructed about it. Thus the Beatles can come across as actively engaged in their Get Back rehearsals, while over a year later, in the throes of their mutual divorce, they mostly remember the disputes.

By analogy: Is it possible that we remember our undergraduate years at Yale as less glowing—or more glowing—than we actually experienced them at the time?

There were many other surprises that jumped out at me from the documentary, a few of which I can highlight here.

- No Selfishness. There was a total absence of “this is MY song” in how they rehearsed or jammed. John and Paul often traded lead vocals on each other’s tunes. Hearing Paul riffing on the vocal of John’s “Strawberry Fields Forever” (which John sang on their 1967 single) was wonderfully unexpected. Or watching John helping Paul with the lyrics on “Two of Us.” John and Paul had often written songs together “eyeball to eyeball” in years prior, but it was refreshing to see them fully engaged in it again—even with the distractions of an ever-present Yoko or a video crew buzzing around them. Also, there was John helping George (in “Something”), George helping Ringo (in “Octopus’s Garden”), and even roadie Mal Evans helping Paul (in “The Long & Winding Road”). At times if you didn’t know how the finished product would turn out you couldn’t have guessed whether a song was John’s or Paul’s. There was none of the rancorous competitiveness between them that was in evidence after the band’s breakup.

- Uncertain Future Plans. The Beatles appeared indecisive about all plans for the future. Would their rehearsals lead to a live concert, a documentary film, a TV special—in addition to a new album? Would the live concert be in the Sahara Desert, in a Roman amphitheater, or on board the QE2 ocean liner? They all agreed they had lost their rudder after the death of manager, Brian Epstein (always referred to as “Mr. Epstein”), who had guided them from the beginning of 1962 through the summer of 1967. The fact that each band member had veto power over any decision didn’t help matters.

- No leader. This points to the leadership vacuum within the band. In the early days John Lennon was the undisputed guy in charge. But by January 1969 he was becoming notably passive—and uncharacteristically non-abrasive—possibly due to the domestic tranquility he was experiencing with bride-to-be, Yoko Ono. (Or maybe he was just high a lot.) Yet Paul, who was later accused by John of trying to run the show, was ambivalent about playing boss. He told George at one point, “I always hear myself annoying you…I’m scared of being the boss.

Yoko Accepted. By 1969 the band members seemed ok that Yoko had become a permanent appendage to John. When John/Yoko were absent at one point, Paul stuck up for her: “She’s great, she really is all right…and he’s not going to split with her just for our sakes.” Speaking words of wisdom, he said it would be funny if historians in 50 years said, “They broke up because Yoko sat on an amp.”

Yoko Accepted. By 1969 the band members seemed ok that Yoko had become a permanent appendage to John. When John/Yoko were absent at one point, Paul stuck up for her: “She’s great, she really is all right…and he’s not going to split with her just for our sakes.” Speaking words of wisdom, he said it would be funny if historians in 50 years said, “They broke up because Yoko sat on an amp.”- No freebies! It was amusing to hear the Beatles lament that despite their name they couldn’t get free musical gear or discounted rates. George complained that the band couldn’t even get a free guitar amplifier from Fender.

- Allen Klein. John raves to George and later to Beatles’ engineer Glyn Johns about his first meeting with Allen Klein, who would eventually become the new manager of the band. “Incredible guy,” John gushes. Glyn offers a much less rosy assessment of Klein, but it fell on deaf ears. Anyone knowing the havoc Klein would wreak on the remaining career of The Beatles has to cringe at these scenes. (Rolling Stone would ominously report that the moment John meets Klein, “The Titanic has just grazed the iceberg.”)

- London Bobbies and the Rooftop Concert. The scenes of the rooftop concert and the police’s patient response to the noise complaints were more detailed and entertaining than in the Let It Be movie. It was fun to witness how diplomatic and deferential the London Metropolitan Police were, even when annoyed about the disturbance. As one young constable told the doorman at Apple, “I don’t mind the noise…personally…but we’ve had about 30 complaints.” The bobbies were successfully detained downstairs in the Apple offices for much of the 42-minute concert. (I can personally attest that this level of understanding and cordiality by law enforcement would not have happened in that period of history in, say, Los Angeles!) As a side note, there were reports of many toilets flushing throughout the Apple building when the police arrived.

- And, in the end, we may have finally found the secret sauce of Beatle success: John and Paul’s two-part vocal harmony. It was omnipresent in their jamming and rehearsing throughout the movie—not always pitch-perfect but uncannily well blended (which can hide many imperfections). If Paul yawned out loud, John would harmonize it. After all, they had been singing together since 1957. 12 years is a lifetime in rock & roll.

Now I know what you’re thinking. “Don’t leave me standing here. There must be more footage to come!” Well, there was a widely reported rumor that Peter Jackson is working on an 18-hour “director’s cut” of Get Back. But, alas, it was based on an article from a satirical site.

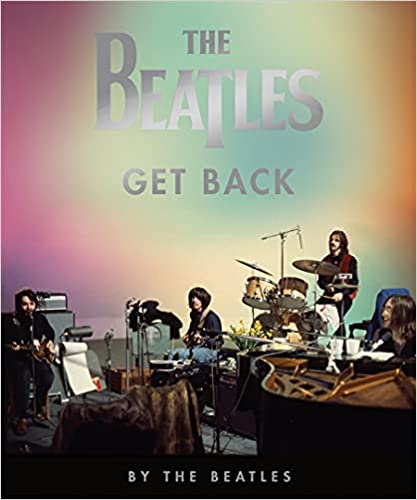

One last thing to mention: Apple Corps released in October an impressive coffee table book—also entitled The Beatles: Get Back—to accompany the film. It includes nearly 500 glossy pix of the rehearsals and rooftop concert (thanks to the photography of Ethan Russell and Paul’s wife-to-be, Linda Eastman) plus transcriptions of more-juicy intra-band dialogue. Though I recommend it, you might need a roadie to carry it around. (It’s 4.37 pounds, 240 pages, and $36, so it’s not for the fair-weather Fab fan.)

If you watched the doc, read the book, or refused to do either, feel free to weigh in with a Comment below!

Watched the series and despite some slow spots, it was beautifully edited and the group’s openness to each others’ contributions was palpable. Preston’s keyboarding really glued the group in ways I’d never appreciated, especially on Get Back. Ringo’s mugging for the camera was no surprise, but his cat-bird-seat vantage at the drum-set and steady gaze conveyed a thoughtful personality that challenged my preconceptions.

At the risk of being drummed out of the class (you know: tar, feathers, rail), I have to admit that I still don’t get it. Your hopeless luddite (then and now), JP

I’m almost through episode 2. My wife has given up because of the tedium. I have never seen so many close-ups of faces dragging on cigarettes, and yet the teeth of the Fab Four seem remarkably white, in those days before stars bleached their teeth. Brief flashes of brilliance, yes, from very talented musicians (all four, incl. the remarkably placid and accepting Ringo). Fun when they cover the songs and intonations of other groups, e.g., the Drifters or the Everly Brothers. Even at this late stage, they obviously like each other, more so than the first movie indicated. Yoko, please, get a life.

OK. If you’re wary, just start with Episode 3, the best by far.

A truly excellent article by someone who fully understands music. Well done!

John—

Thanks. I really enjoyed reading it

—David Lawrence

Thanks so much for this, John. And if you only have four minutes, try Walk Off the Earth’s Beatles Medley:

https://www.google.com/search?q=walk+off+the+earth+beatles+medley&oq=walk+off+&aqs=chrome.0.69i59j69i57j35i39j46i20i263i433i512j0i512j46i512l2j0i512j46i512j46i67.3186j0j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8

I LOVE Walk Off The Earth, my favorite modern band. Great medley. Thanks.

Thanks for introducing me to Walk Off the Earth. I just loved the medley. I hadn’t realized just how hard wired many of those Beatles songs were into my brain.

I admit to being the owner of one of those Rubber Souls. It was the first Beatles album I owned, a gift from my floor mates in Farnam Hall. I’ve been a confirmed fan ever since. In my five-decade musical career, I have played in orchestras, bands, musicals, studios, and contemporary ensembles. My first love has always been chamber music, and Jackson’s documentary, in my view, is a beautiful expression of the creative dynamics that result in great chamber music. Three cheers for live music- no click tracks.

Great stuff, John. Thanks. Cooperation versus competition in music fascinates me especially in jams. I graduated from the Beatles to the Band with a huge dose of chamber music senior year. My amateur’s ear was amazed at our time of music.

How did you see The Band or the Dead and their music? The all owed much to Dylan and the Beatles, of course.

Lots to comment on, Jonathan! It seems to me the embrace of both cooperation and competition is at the heart of success in most human endeavors, especially music, and especially with The Beatles. Lennon and McCartney recognized early on that each was a talented songwriter but they needed to work together to be “bigger than Elvis.” So they agreed that whoever wrote a song, it would be credited to John Lennon and Paul McCartney. They would both share equally in the earnings of any of their songs, removing any financial divisiveness. http://businesslessonsfromrock.com/notes/2016/03/cooperative-competition-another-business-lesson-from-the-beatles

The Band and The Grateful Dead are two excellent examples of individual talent and collective artistry. My band, The Morning, after leaving Yale in 1968, opened for the Dead multiple times in NY and LA—even living with them briefly—and saw that “jam phenomenon” up close. Same dynamic with The Band, though Robby Robertson claimed exclusive ownership of many of their songs, which later alienated him from other band members, especially Levon Helm. https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2020/aug/30/were-the-bands-songs-written-as-collaborations/ I was doing some session drumming at Richard Alderson’s studio in NYC in the summer of 67 after Alderson had worked as Dylan’s live recording engineer on the 1966 tour, backed by most of The Band. At night I slept in the back room of the studio amid The Band’s equipment, on a Fender Bassman cabinet with Bob Dylan’s name stenciled on the back of it. The closest I ever came to greatness.