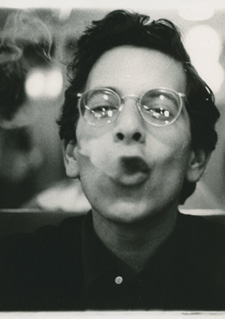

Paul Allen Rosenberg – 50th Reunion Essay

Paul Allen Rosenberg

14 Standish Street, PO Box 610229

14 Standish Street, PO Box 610229

Newton, Massachusetts 02461

paul.rosenberg@childrens.harvard.edu

617-905-7057

Spouse(s): Harriet Claire Moss, 1981

Education: Albert Einstein College of Medicine MD, 1978; PhD, 1979

Career: Residency in neurology, 1979-1982 (Longwood Area Neurological Training Program); staff physician in the Department of Neurology, Boston Children’s Hospital, 1986 to present, now Senior Associate in Neurology; Associate Professor of Neurology, Harvard Medical School

Avocations: running, fitness, swimming in the Caribbean, music, theatre, literature

College: Trumbull

Early in my freshman year, enjoying my courses but feeling something was missing, I wrote a letter to Edward Adelberg, a molecular biologist at Yale, with an idea for a project I had been thinking about for years. I was deeply intrigued by bacterial transformation, discovered by Oswald Avery, which I had read about in Scientific American. Remarkably, one strain of bacteria could be transformed into another using purified DNA—implicating DNA as the genetic material of cells. My idea was that maybe malignancy in animal cells was a trait that could be similarly transferred. After about six weeks I received a letter from Dr. Adelberg, from Paris, on stationary of the Pasteur Institute. He apologized for the delay and explained that he was on sabbatical. He was very gracious, thanked me for the inquiry, expressed interest in the project, but went on to say that to pursue it I needed to learn “everything there was to learn about cancer, molecular biology, and microbiology.” At the time I took this advice as discouraging—how could I possibly do this?—but now I realize what he said was essentially correct. Perhaps I wasn’t ready to immerse myself so completely in science, because so much else was interesting to me, and I had a lot to learn. I majored in history, the arts, and letters, strongly influenced by my freshman advisor, Bill Redpath. I found in HAL a committed faculty and a small band of students who were both brilliant and congenial with whom to study western culture.

I applied to medical schools a year after graduation. Applying to a combined MD/PhD program at one school involved just checking a box, which I did almost on a whim. At the interview, I talked about the transformation project and was able to tap into the enthusiasm for the project that originally motivated me. The two interviewers seemed to respond and I was accepted into the combined program. There, I rediscovered the part of myself that was deeply interested in science. I ultimately became a neurologist and neuroscientist, and, miraculously, continue to receive NIH funding for my lab. It turns out the trajectory of studying literature in college followed by neurobiology is not so rare. In my case this path highlights a number of lessons: 1) the importance of readiness; 2) the need to overcome self-defeatist views to rise to challenges; 3) the great impact a mentor or potential mentor can have on a young person; and 4) that our mentors pose challenges to us not to defeat but to elevate.

My lasting memories of Yale include those of certain great teachers, especially Earl Ramsey, who taught my English 25 seminar, in which the discussion often came back to love and desire, and, a favorite word of his, concupiscence. When I was 20 and a sophomore I met the person I have loved and lived with most of my life, Harriet Moss. We remain together now 51 years after first meeting.

If the above is blank, no 50th reunion essay was submitted.