Spin Training Shouldn’t Be Optional

Editor’s Note from Harry Forsdick: There are moments in each of our lives where we have learned a lesson we will never forget. Sometimes these lessons get recorded in a form that can benefit others — whether it be a book, a photograph, a magazine article, or a radio interview.

Steve Bemis had one such incident in his life when he was learning to fly a small plane. Steve writes:

Gentlemen – I saw the invitation to submit published articles for the reunion and the website. I thought little of this, since my sole published effort is trivial compared to that of many in the class.

Recent stories of big planes going nose up and being instructed by their computers to dive jogged my memory, however, since my one article was about spin training – a spin being what can happen after a plane’s nose gets too high, the wing stalls and the plane stops flying.

If one is lucky and has control of the plane, and has enough altitude, what then follows when the nose points down, is a dive. In my case, with no computer telling me to dive, something clicked from the voluminous reading I’d done in learning to fly. I pushed the stick forward (after desperately pulling it into my stomach), and got the sweetest kick in the pants as the wings started flying again.

What follows the stall and recovery from the spin is a dive – again assuming control of the plane and enough altitude – and after entering the dive, you need altitude and recovery from the dive. Both. Really need.

This is not rocket science. It seemed crazy to me then that no pilots other than CFI (certified flight instructor) were required to have spin training. It was explained to me at the time that he training itself was deemed too dangerous. My understanding (I no longer fly) is that the CFI and aerobatic pilots are still the only pilots who get spin training. Otherwise, it’s still optional.

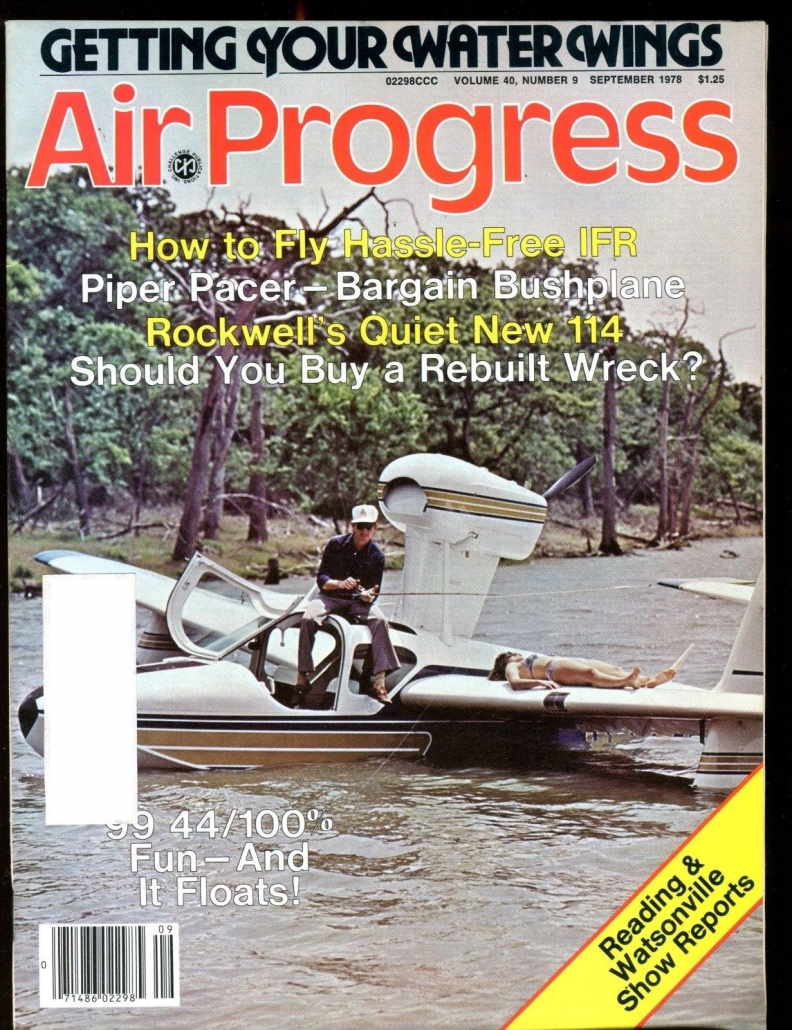

I experienced my first spin when I was learning to fly back in early 1978, and I wrote the attached article which appeared in the September, 1978 issue of Air Progress magazine, Vol.40, No. 9.

I was taking independent flying lessons. Got my license and flew a bit more, but had a few more experiences (totally following the rules) which convinced me that the publicity about the safety of general aviation was skewed, and that my young family needed me to find a safer hobby.

– Steve

———

Here is Steve’s article from the September 1978 issue of Air Progress magazine, Vol.40, No. 9

Spin Training

Spin Training

It Shouldn’t Be Optional

A word in favor of required spin training from one of the lucky ones.

by Stephen T. Bemis

Editor’s Note: This article was written before the publication of Budd Davisson’s excellent piece on spin training (June 1978). Steve Bemis got into an inadvertent spin before receiving any formal spin training; If he’d panicked, or if he’d been flying some thing less forgiving than a 150, this article might well never have been written. It’s a sobering lesson and reinforces our contention that pre-solo spin instruction should be a mandatory part of every pilot’s training.

After soloing in the middle of the winter I had accumulated a couple hours of solo touch and go practice. Weather was a major factor in my training schedule, and it seemed like every weekend found our local airport in strong crosswinds across its one runway 18/ 36. Consequently dual time built up, and my instructor had managed to cover night and tower work as well as two cross countries with me. With about 25 hours total under my belt, and preparatory to the solo cross-country regimen, he wanted me to get some more local solo practice. We planned to work on some actual spins just before I was to set out alone cross-country, and we discussed spin recovery briefly. My mentor told me not to try to spin solo, and had no trouble getting me to agree to wait. I had heard and read about spins and had absolutely no desire to introduce myself to the maneuver.

Thus it was on a bright Saturday morning in March that I was up in a venerable (or, if you prefer, a plus- 2000 hour 1974) Cessna 150 trainer practicing stalls, slow flight, and other exercises. In the stall practice I became aware that the stall warning horn had stopped working. This didn’t seem to be a real problem for stalls. However in slow flight I had learned to try to keep that horn just squawking. So as I flew in a full-flap, slow flight configuration, I was preoccupied trying to hear something from the stall warning horn, thinking perhaps it was simply weak rather than broken completely. From what l remember next, I must have entered a level, mushing stall. As I was trying to keep everything level, suddenly all I could see was the ground, straight down, passing rapidly before my startled eyes from right to left in a gentle arc.

It clicked in my head that I was in a spin, and that somewhere in my instructor’s comments, in the many flying manuals, books and magazines which I had devoured in the past months – somewhere, there was a standard set of procedures to get me out of it. In my stomach, however, some muscles contracted and hauled the stick back into my lap, and I tried to maneuver with aileron to stop the spin. To my consternation, things did not improve. Panic did not set in, since the stall routine had started at about 3000 feet AGL, and so I had room to recover — if I could figure out what to do. I also thought about the 40 degrees of flaps which were hanging out; however, it didn’t seem like the right time to divert any attention to bringing them in.

As I completed what must have been one or one and a half rotations I became more concerned. Gradually (time seemed to move slowly in some ways) I reasoned that my stomach was not helping me do the right things. In a move which is best described as very hopeful (if not desperate), I straightened the wheel and pushed my arms out. The resulting solid thump of lift was one of the finest feelings I’ve ever had. As airspeed built up I had the presence of mind to reach over and push the flap switch up. Speed did not get over 130 mph in the recovery and my resulting altitude was about 2000 feet AGL. After a yell or two of relief, I proceeded back to the home field, straight and level, and made one of the sweetest crosswind landings I can remember.

As I completed what must have been one or one and a half rotations I became more concerned. Gradually (time seemed to move slowly in some ways) I reasoned that my stomach was not helping me do the right things. In a move which is best described as very hopeful (if not desperate), I straightened the wheel and pushed my arms out. The resulting solid thump of lift was one of the finest feelings I’ve ever had. As airspeed built up I had the presence of mind to reach over and push the flap switch up. Speed did not get over 130 mph in the recovery and my resulting altitude was about 2000 feet AGL. After a yell or two of relief, I proceeded back to the home field, straight and level, and made one of the sweetest crosswind landings I can remember.

As a student pilot, it seems incredible to me that spin training is not required. Simply instilling respect for and prevention of spins (read that fear of spins) in students, and then certifying them to fly with others with no actual spin training can, and apparently often does, have fatal consequences. Mere description of spin recovery is like the classic “steer into the skid” advice given student drivers. Steering into a skid in a car or effecting a spin recovery in a plane makes little sense in the abstract. It must be practiced.

It goes without saying that my good luck with a forgiving 150 probably would not have been as good in a “non-spinnable” Grumman or similar plane. Obviously, I erred in the practice maneuver by concentrating too much on peripheral matters and not flying the airplane. I do feel that it won’t be the last time I make some kind of an error in a plane, however, and I’m sure many students also make similar errors solo as well as dual.

If I look at my experience pessimistically, I would have been a statistic if I’d failed my impromptu “lesson.” In this respect I don’t blame my instructor; unlike many, he fully intended to teach me spins. His cautioning me about them and our brief discussion of recoveries probably helped me get my head together as I watched the rotating landscape.

On the optimistic side, I’ve concluded that the unexpected way I learned about spins was better than any contrived practicing because spins most often happen this way. And the recovery technique is, needless to say, etched deeply in my mind. Even contrived practice is better than none, however, especially since no matter how you get into the spin, the recovery remains all-important and it can be practiced.

In a way it’s a relief having had an unexpected spin (and survived). As my instructor and I reviewed my Saturday lesson, he summarized that a stall /spin “is just about the worst thing that an airplane can do to you.” If this is true, I can take a second wind now and proceed with some confidence that, at this point in my training, I have some idea what the worst can be like.

Steve commented on the Ethiopian Air crash and his comment was picked by the Editors as a “NY Times Pick” — see https://nyti.ms/2YQNpCV#permid=31403698