Staughton Lynd Dies at 92

from NYTimes

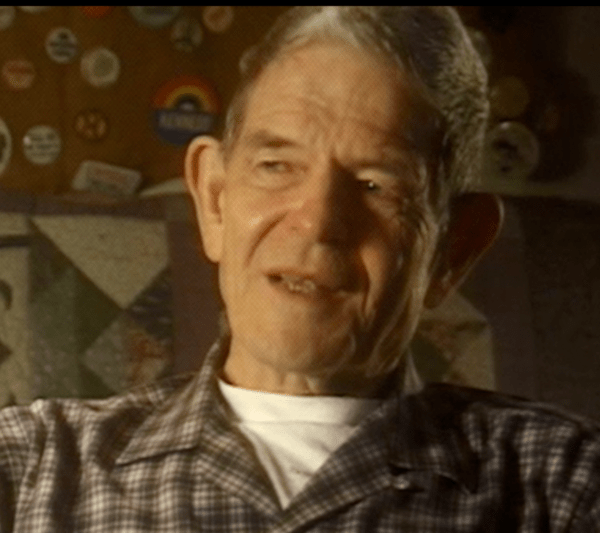

Staughton Lynd, Historian and Activist Turned Labor Lawyer, Dies at 92

After being blacklisted from academia for his antiwar activity, he became an organizer among steel workers in the industrial Midwest.

Staughton Lynd, a historian and lawyer who over a long and varied career organized schools for Black children in Mississippi, led antiwar protests in Washington and fought for labor rights in the industrial Midwest, died on Thursday in the town of Warren, in northeast Ohio. He was 92.

His wife and frequent collaborator, Alice Lynd, said his death, at a hospital, was caused by multiple organ failure.

Mr. Lynd was one of the last of a generation of radical academics — including his friend and colleague Howard Zinn — who in the 1960s overthrew their predecessors’ obsession with detached, objective scholarship in favor of political engagement.

Many of his colleagues stayed within the bounds of academia, but Mr. Lynd burst beyond them. As a young professor at Spelman College in Atlanta, he led students in marches against nuclear weapons. In 1964 he was one of the main organizers behind Freedom Summer, which brought Northern college students to Mississippi to teach and organize in Black communities.

When the Vietnam War was still relatively new and most Americans still supported it, he organized antiwar protests in Washington. He was among the first of about 350 people arrested during one demonstration — though not before neo-Nazis, staging a counter protest, dumped paint on him and two other marchers, David Dellinger and Bob Moses. A photo of the three bespattered men appeared in Life magazine.

Image

In 1965 Mr. Lynd joined another radical historian, Herbert Aptheker, and a founder of Students for a Democratic Society, Tom Hayden, on a trip to North Vietnam. There they met with Communist leaders and made global headlines, but also numerous enemies back home. The trip effectively ended Mr. Lynd’s career at Yale, where he had moved just a year before.

Mr. Lynd was not a communist, though he was often mistaken for one. Instead he made his own way on the left, drawing equal inspiration from Marxism, American abolitionism and Quaker pacifism — a diversity that helped explain his involvement with so many different movements.

“Staughton was very unusual,” Gar Alperovitz, a historian who wrote several books with Mr. Lynd, said in a phone interview. “He walked a path that was his own. And when it intersected with the activist groups on the progressive left, he would be involved. But he was a very moral political figure rather than a tactical one.”

In age he fell between the Old Left, which cut its teeth in the 1930s and ’40s, and the New, which was coming up in the ’60s. There was no question where his loyalty lay: He reveled in the impassioned spontaneity he encountered as a professor on college campuses, and students flocked to him in turn.

At Yale they would cram into his office or gather on his living room floor to hear him take on all comers, staking positions to the left even of outspoken liberals like the Yale chaplain William Sloane Coffin, a frequent verbal sparring partner.

Even as he developed a following as an agitator, he built a reputation as a pathbreaking historian. His best-known book, “The Intellectual Origins of American Radicalism” (1968), opened new ground by identifying members of the Revolutionary War generation who embraced abolition and equality, and it won praise even from establishment historians.

“Of all the New Left historians, only Staughton Lynd appears able to combine the techniques of historical scholarship with the commitment to social reform,” David Herbert Donald wrote in a 1968 review in Commentary.

But his academic star soon fizzled out. By the end of the 1960s, his outspoken activism had drawn the attention of the F.B.I. and gotten him blacklisted from higher education, even from small urban colleges in Chicago, where he and his family had moved in 1968.

Image

He pivoted, involving himself in labor organizing among the factories that lined the southern shores of Lake Michigan. He received a law degree from the University of Chicago in 1976, after which he and his wife moved to Youngstown, Ohio, where workers, union leaders and owners were fighting over the impending closure of the city’s steel mills.

To the frustration of both the union bosses and the mill owners, he sided with the rank and file, writing a handbook for workers trying to navigate the legal system. In the early 1980s he helped lead a high-profile effort to turn the mills over to a worker-owned cooperative. Though the effort failed, it brought him renewed acclaim on the left.

He did much of his later work alongside his wife. She wrote several books with him and, after getting her own law degree, joined him as a partner. They officially retired in 1996 but continued taking pro bono cases, this time with a focus on the death penalty and prison reform.

“Whether in his pathbreaking historical work on the roots of American radicalism, his active participation in campaigns for civil rights, his crucial role in steps toward democratization of the economy, Staughton Lynd was always in the forefront of struggle, a model of integrity, courage, and farsighted understanding of what must be done if there is to be a livable world,” the linguist and left-wing scholar Noam Chomsky wrote in an email.

Staughton Craig Lynd was born on Nov. 22, 1929, the same year that his parents, the sociologists Robert and Helen Lynd, published their book “Middletown,” based on their research in Muncie, Ind. It was one of the first books to offer a comprehensive study of an American community, and it established them as two of the country’s best-known academics.

The Lynds lived in New York City — Robert Lynd taught at Columbia, while Helen Lynd taught at Sarah Lawrence College — but Staughton was born in a hospital in Philadelphia because his mother preferred the doctors there.

He grew up among the New York intellectual set, attending the Ethical Culture School and the Fieldston School, and entered Harvard in 1946.

He studied social relations, a popular but now defunct major. In his free time he dabbled in radical politics, joining the Communist Party-aligned John Reed Club and briefly participating in two Trotskyist organizations on campus.

During the 1950 summer school session he met Alice Niles, a student at Radcliffe. They married the next year.

After graduating in 1951, he spent time studying urban planning before being drafted into the Army in 1953. As a conscientious objector, he was given a noncombat role, despite the continuing Korean War.

A year later, though, he received a dishonorable discharge after Army investigators dug up his Communist affiliations in college; they also highlighted his mother’s career as a “modern” professional woman.

He and others with similar disqualifications appealed, and the Supreme Court eventually ordered the Army to give them honorable discharges instead. The change in status allowed Mr. Lynd to take advantage of the G.I. Bill, which he used to pay for graduate school.

But first, he and Alice spent three years living on a Quaker commune in northern Georgia. They then spent six months in a similar community in New Jersey, where he first met Mr. Dellinger, a like-minded pacifist who brought him on as an editor at his magazine, Liberation.

The Lynds finally returned to New York City, where Mr. Lynd worked for a tenants’ rights organization on the Lower East Side and pursued a history doctorate at Columbia.

He received his degree, with a dissertation on New York State during the Revolutionary War, in 1962. By then he and Alice were already in Atlanta, where he got a job teaching at Spelman (and where Mrs. Lynd babysat the children of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., a neighbor).

Among his colleagues was Mr. Zinn, who would be fired for his activism in 1963, and among his students was Alice Walker, who would go on to write “The Color Purple.”

Mr. Lynd became actively involved with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and grew particularly close to one of its leaders, Bob Moses, a similarly cerebral activist. In 1964 Mr. Lynd was chosen to oversee the educational component of Freedom Summer, instituting curriculums and training teachers for the many schools that were to open across Mississippi.

He was in Oxford, Ohio, where organizers gathered before heading to Mississippi, when he first heard about the kidnapping and murder of the civil rights workers James Chaney, Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman.

“I’ll never forget Mickey Schwerner’s wife, Rita, pacing one of the rooms all night long, waiting for word of some kind,” he wrote in The Bill of Rights Journal in 1988.

That fall Mr. Lynd joined the Yale history department, though by then he was spending more and more of his time as an activist.

In June 1965 he joined another antiwar protester in a lonely demonstration outside the Pentagon. Almost immediately, dozens of military police officers had surrounded them.

“What in the cotton-picking world do you think you’re doing?” he recalled one of them asking.

He straightened himself up, looked at the officer, and replied: “You don’t understand. We’re the first of thousands.”

His trip later that year to North Vietnam, and a 1966 trip to London, where he blasted American foreign policy on the BBC, persuaded the State Department to revoke his passport.

Image

In 1968 the Lynds moved again, to Chicago, where Mr. Lynd was eager to get involved with the labor movement. He taught briefly at two local schools, Roosevelt University and Columbia College, and applied unsuccessfully to others. But he failed to find a permanent contract — the result, he insisted, of a concerted effort to blacklist him from teaching.

He then worked briefly for the social activist Saul Alinsky’s Industrial Areas Foundation, and he and Alice Lynd wrote an oral history of Chicago labor, “Rank and File: Personal Histories by Working-Class Organizers” (1973).

Mr. Lynd wrote more than 20 more books and extended pamphlets, mostly about labor organizing and prison reform. An exception was “Stepping Stones: Memoir of a Life Together” (2009), written with his wife.

A year later, an interviewer for Harvard Magazine asked him why, after such a long career, he was still so active.

“At age 16 and 17, I wanted to find a way to change the world,” he said. “Just as I do at age 79.”

Clay Risen is an obituaries reporter for The Times. Previously, he was a senior editor on the Politics desk and a deputy op-ed editor on the Opinion desk. He is the author, most recently, of “Bourbon: The Story of Kentucky Whiskey.” @risenc