Survey 7: Religion and Spirituality

For Whom, for country, and for Yale?

For Whom, for country, and for Yale?

Religion and spirituality in the Class of 1969

“The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom.”

—Proverbs 9:10

“Urim and thummim.”

—Yale seal (Hebrew script meaning either “lights and perfections” or “curses and blessings” depending on translation, see Exodus 28:30)

“Acquire the Holy Spirit, and a thousand around you will be saved.”

—St Seraphim of Sarov

“Il faut imaginer Sisyphe heureux.”

—Camus (“One must imagine Sisyphus as happy.”)

In a way, this essay reflects a journey of discovery. Over the four years during which it progressed from glint in my eye to finished work, I myself progressed, I suppose, from total ignorance to relative ignorance. The topic of that ignorance: the religious views of our class.

If I thought about the subject at all from 1965 to 1969, I probably assumed our class represented a reasonable cross-section of American beliefs, or at least educated American beliefs. So, it was with great surprise that, at our 45th reunion, I learned that among a group of classmates I thought I knew pretty well, I was the only one who believed in God. Their reaction, in fact, seemed to say, “Well of course not—who does?” When I told them that I do, and in fact have a stronger faith than I had back then, they seemed to regard it as an eccentricity—a harmless one, to be sure, like the fact that I kept wearing a coat and tie even after the coat-and-tie rule was rescinded, but an eccentricity nonetheless.

That encounter spawned a casual offer to write this article for this Classbook, which was accepted with an alacrity that should have warned me I’d bitten off more than I might want to chew. I began sporadic researches into sociological trends, and when we created the class survey instrument in 2017, I inserted questions about religion and an invitation to submit stories. The results of the Survey and conversations with selected classmates—quotes from which are scattered throughout this essay—confirmed my 2014 encounter, but with a great deal more nuance than “Who does?” Spiritually speaking, the Class of ’69 has traveled a different road from the country as a whole—or perhaps a similar road at an accelerated pace.

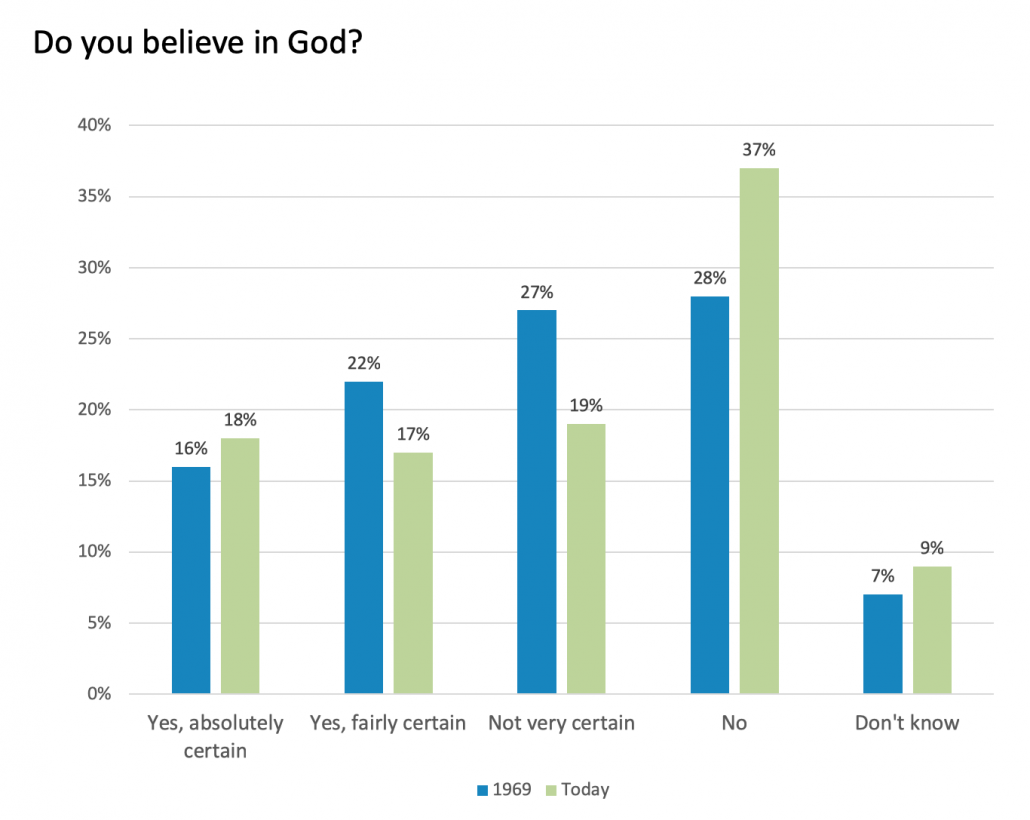

Looking at the numbers

Let’s start with my original question: “Do you believe in God?” Thirty-seven percent of us say flatly “No,” compared to only 9 percent of a national sample done by the Pew Research Center. The General Social Survey (GSS), the national longstanding longitudinal measurement of US social attitudes funded by the National Science Foundation, shows a still lower number. That can depend on how you ask the question—for instance, 8 percent of Pew respondents calling themselves “atheists” still say they believe in some kind of God. Lest you immediately assume it’s just that belief is only for uneducated people, the GSS found only 5 percent of college grads say “No”—a result that’s stayed remarkably stable since 1988. Levels and expressions of belief have decreased a lot over the decades, of course, but our class was and is a pretty skeptical bunch, as shown in the then-and-now summary of our beliefs in Figure 1.

Based on recollections of belief as reported in the class survey, then-and-now comparisons show a slight uptick in “absolutely certain” belief, but overall the trend is toward less faith rather than more. When you examine where the gains and losses came from (“cross-tabs,” for those who remember your stat courses), most of the movement is in the middle. We had relatively few dramatic stories of totally lost faith, or of Road to Damascus experiences (see Acts 9 if that reference is obscure to you). Of those “absolutely certain” of God’s existence in 1969, 86 percent still are, and atheists are just as true to their (dis)belief: 89 percent of 1969 atheists still are. Agnostics (“not sure”) are also pretty steadfast in their indecisiveness (79 percent). It’s those who recall being lukewarm in 1969 (“fairly certain” or “not very certain”) who largely have chilled further. Those categories are two to three times more likely to report less faith than more faith, compared to 50 years ago. And since those two categories made up 49 percent of the class, their loss of faith accounts for the overall change. “Belief in an afterlife” shows similar trends.

While the absolute numbers are out of line with the country, directionally they actually follow a national trend: polarization. Research published by scholars at Harvard and Indiana University in 2017 drilled down into the apparent “secularization” trend reported by many surveys and concluded, in fact, that “…only moderate religion has declined and that the intensity of American religion is persistent and exceptional” compared to other countries in the world. Just as our class is more divided than it was in 1969, so is the rest of the country. And among us there are more fervent believers than there were, as some of the quotes called out in this article will indicate.

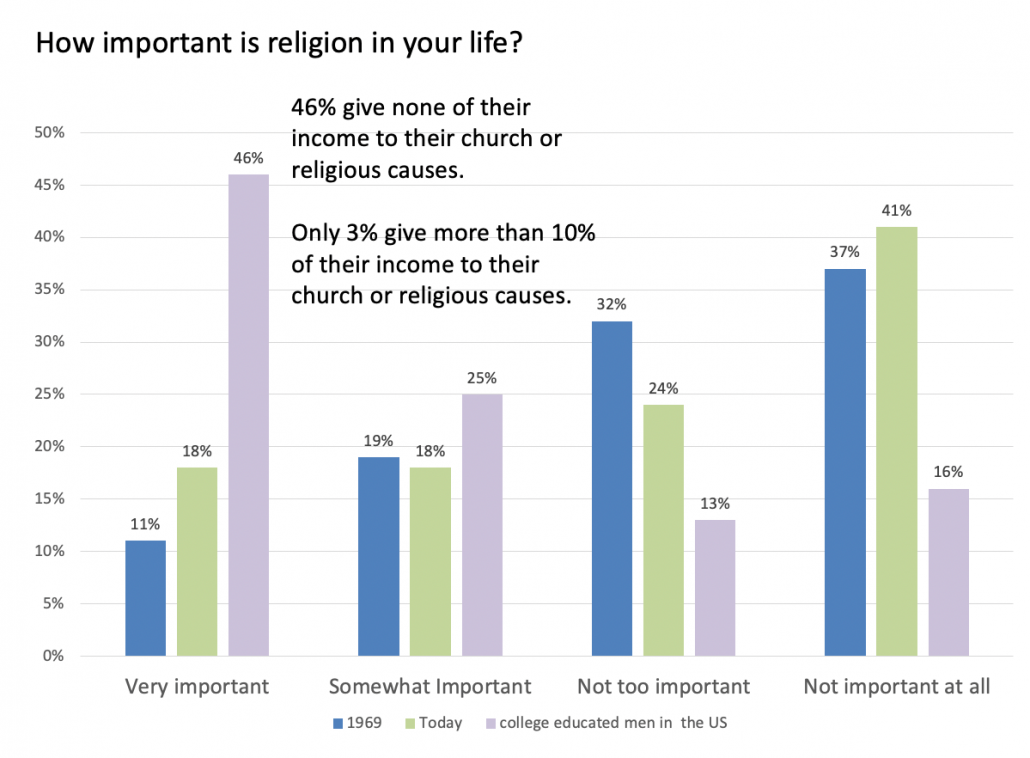

When the question is “importance of religion,” the pattern is slightly different, as Figure 2 shows. “Very important” responses increased about 80 percent from 1969, albeit from a low level; “not important” increased much less. And the middle-of-the-road people are more evenly divided, with those who would have said “not too important” in 1969 as likely to have gone up the scale since then as to have gone down. Again, lest we think it’s just a matter of education, the third bar in the chart compares us to all 65-75 year old college educated men in the U.S., according to Pew. Religion is very or somewhat important to more than 70 percent of that peer group, compared to only 36 percent of us ’69ers today. And we’re twice as likely to say “not important at all.”

Here as in belief in God, we’re also at variance with our Baby Boomer generation as a whole. Boomers are four times more likely than we are to believe in God “absolutely” (69 percent vs 18 percent) and religion is very important to three times as many (59 percent vs 18 percent) according to the Pew Religious Landscape survey from 2014. We were out of step in 1969 and we still are.

Who gained, who lost?

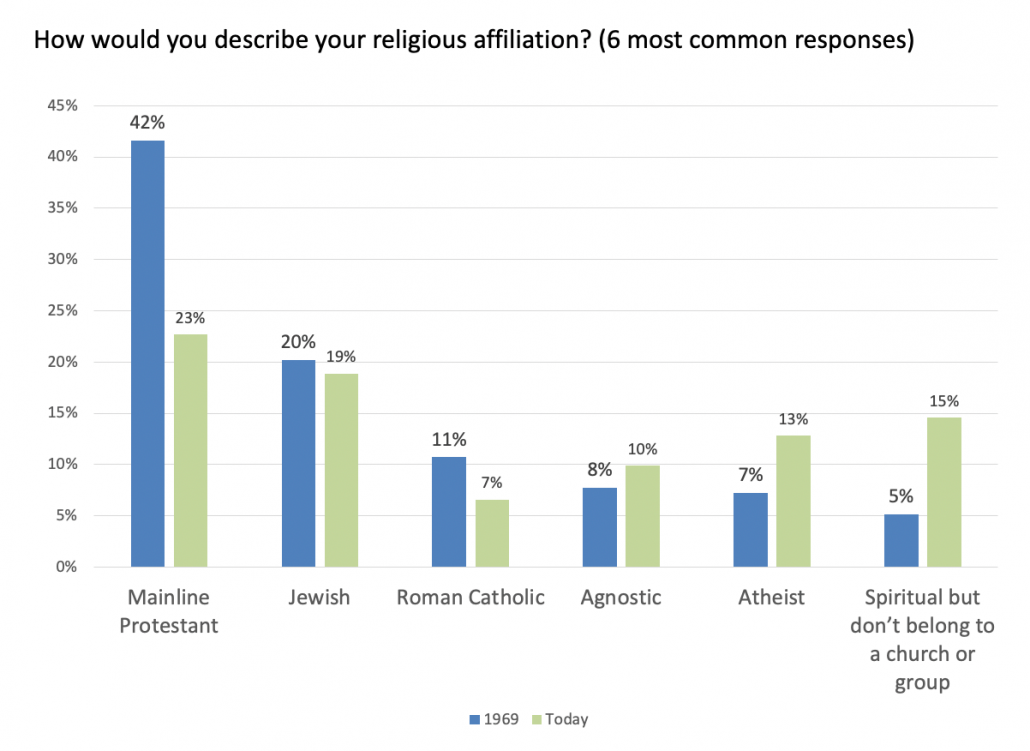

Faith, of course, is not a single linear function. Even those of us who believed in 1969 came to Yale professing many faiths. To simplify the class survey, we didn’t provide as many choices as the more in-depth instruments like the GSS. Instead, we offered what I thought would be the main categories, like “Roman Catholic,” “Jewish,” “mainline Protestant, “evangelical or fundamentalist,” and so forth. We did allow respondents to choose “other” and specify other religions, but few did. Figure 3 shows the breakdown of the six most common responses, 1969 and now.

In 1969, compared to the general population (GSS 1972, first year it was done), we were somewhat less Christian (about 55 percent total vs about 64 percent nationally), ten times more Jewish (20 percent vs 2 percent), and a lot more atheist and agnostic (about 15 percent vs only 5 percent on the GSS). Since then, about 40 percent of the Class of ’69 changed affiliations in one way or another. Taken as a whole, atheists, agnostics, and “spiritual but don’t belong to a faith or group” increased to more than a third of the class.

The biggest overall change in our class, which doesn’t show as starkly on the chart but is revealed by cross-tabs, was among Christians: 43 percent no longer identify as Christian of any kind. The GSS shows a reduction in professing Christians too, but much smaller. Between the ’70s and 2016, Christians nationwide went from 89 percent of respondents to 73 percent, implying a decline perhaps a third as big as ours. Even leaving aside those who still belong to a church but don’t believe its doctrines, which I’ll deal with later, that’s a big difference in self-perception of faith.

The stories behind the numbers

So, let’s stop with the statistics for a moment. What have we learned that maybe I should have known already but didn’t?

- We were majority Christian, but then and now, a lot more Jewish than the country as a whole.

- We started out an unusually impious bunch, and have gotten more so a lot faster than the rest of the country.

- But regardless, many of us find importance in some form of “spirituality,” even if we reject the idea of “religion,” and maybe even reject the idea of God.

Before we delve further into those points, maybe this is where I should “declare competing interests” as they say in medical research, and summarize my own spiritual journey.

I was raised Unitarian, mostly because it was the only church my parents (secular Jew, lapsed Catholic) could agree on. Back then Unitarianism was summed up by our common joke that Unitarians pray “To whom it may concern.” At Yale I was just as immersed in studies, activities, and bull sessions as the rest of us. Religious observances were pretty much limited to taking unusually pious dates to church Sunday mornings. But I kept thinking—as clearly many of us did and do—“there must be something more.” After return to Chicago I started attending a little church near my apartment, where I met my future wife (like many of our classmates with similar arcs to their lives). I was baptized an evangelical Christian, we married, we set to raising an evangelical Christian family. Then about 20 years later we discovered the (Eastern) Orthodox church, which provides a 2000-year-old structure of belief, worship, and practice designed to make daily life sacramental. Our family was received into Orthodoxy at the start of the new millennium. Our elder daughter is married to an Orthodox priest. Church and family are the core of my life.

That big swing from a sort of institutional agnosticism to the most traditional of Christian faiths colored my assumption that many of us might have also made big spiritual journeys. As it happens, some did, some didn’t, and the types of journeys varied significantly.

The faithful Jews

Maybe the high percentage of Jews at Yale in the ’60s should have been obvious to someone named “Baum,” but my own Jewish heritage was at least a generation behind me. So I wasn’t involved in Hillel, for instance, though aware that it was quite an active group. But the fact is, Yale has long been one of the most Jewish universities in the country; #1 today at 27 percent (according to Hillel), though Harvard is a close second. (Nationally, Jews are 5 percent of the college population today.) By and large Jews are the most steadfast group. Crosstabs reveal that 85 percent of classmates who identified as Jews in 1969 still do.

Of course, being a Jew is not just about faith; it is about identity. Hillel’s national survey found that 80 percent of Jewish college students today say “Jewish” is a cultural group, vs 57 percent saying it’s a religious group (multiple responses were allowed). Fewer than a quarter of young Jewish college kids call themselves “religious.” In 1969, too, Yale Jews were somewhat less likely to be “absolutely” or “fairly” certain of the existence of God than the class as a whole (28 percent vs 35 percent), and it hasn’t changed much today. Being “Jewish” can survive some pretty fundamental changes in beliefs and practices, though, such as our Jewish classmate who identifies himself “spiritually Tantra Yoga.” And the Jewish identity is perhaps even less homogeneous than the Christian one: for example, the classmate who calls himself “very Reform but with strongly held views opposed to other ‘flavors’ [of Judaism].”

Still, Judaism as a whole seems to provide a tangible “something” to hold onto, even as much else in one’s life and beliefs is changing. Judaism has even gained a handful of Christian converts from our class in the past 50 years (no one has moved in the other direction). One left a Christian background that had lost its meaning for him and converted to his Jewish wife’s faith. They raised their kids Jewish and still attend services, but both of them today are more agnostic than believing. Judaism for them seems to supply a venue for considering things beyond what he calls our “finite experience.” He says he finds meaning in the “universe of life,” an essentially existentialist viewpoint like that of Holocaust survivor Victor Frankl, whose Man’s Search for Meaning has been significant to him.

Was it something in the water?

What about the 80 percent of Yale ’69 who weren’t and aren’t Jewish, who started out more skeptical than the nation and haved moved around the spectrum so much since? Clearly, the Class of ’69 never represented a typical cross-section of American society in our spiritual views, any more than did, or does, our financial profile, cultural background, or gender makeup. Is there something about the admission process that skewed us as a sample? Actually, gender (or “sex” as we used to call it) might account for some of it—the GSS indicates that men have always been about twice as likely as women to be unbelievers, though only slightly less likely to believe “absolutely.” Social class might account for some of it, too; self-identified members of the “upper class” skew toward lack of faith, though there’s no way of knowing how many of our class thought or think of themselves that way. But those two factors together are not nearly enough to explain the whole variance.

Was it something in the Yale experience itself? One view is that our intellectual training encouraged a skeptical spirit that informed our lives. “At Mother Yale’s bosom I learned to question authority and look for the Good Stuff,” one of our classmates recounts, going on to say: “I moved from ‘If it feels good, do it’ to ‘Still waters run deep’ and found it in the practice of [transcendental meditation].” Once off the Old Campus and no longer bombarded by the bells of Battell Chapel, we found it easy to plunge into a completely secular, not to say hedonistic, lifestyle. One of our Jewish classmates says that of all the Jews he knew at Yale, only one was observant after freshman year. A classmate who was raised Lutheran, married a reform Jew, attended the United Church of Christ for much of his life, then recently earned a divinity degree from a Lutheran seminary recalls: “Yale was a bit of a dry spell.” Though he admits: “Having volunteered for the Marines freshman year left me something of a pariah in campus religious circles.”

How much of it was the ’60s?

Which raises the question: Did Vietnam (and the other social upheavals of the ’60s and ‘70s) affect our religious views? On the face of it one might think so. Perhaps the most visible Christian during our days at Yale, chaplain William Sloane Coffin, in some ways personifies the thought trends that shaped our generation. Though he himself was of course not a baby boomer, he was like us in a lot of other ways: child of privilege, heir of the establishment. He served in the CIA during the Korean War. Like most of us, he was deeply affected by Vietnam, which colored his views and his public persona at Yale. For 10 years after he left Yale he served as senior pastor at the prominent Riverside Church in New York City, whose combination of affluence and social activism mirrors Coffin’s background. Then he left the active ministry to pursue political and social causes.

Yet one of our classmates who knew Coffin both during and after the Yale years found him a deeply committed Christian with a depth of insight into the Gospel that led that classmate himself to the ministry some years later. Coffin delivered powerful Christian witness even to the end of his life. In an interview two years before he died, he said:

When we see Christ empowering the poor, scorning the powerful, healing the world’s hurts, we are seeing transparently the power of God at work. God is not too hard to believe in. God is too good to believe in, we being such strangers to such goodness. The love of God is to me absolutely overwhelming.

This is a dramatic contrast to many of the comments from 1969 unbelievers that rationality or evil in the world have erased God from their perception of the universe. Even on the afterlife, Coffin remained steadfast: “I believe our lives run from God, in God, to God again. And that’s enough.” Had he taken the 1969 class survey, that suggests “absolutely certain” to me. So Vietnam, while it may have helped drive William Sloane Coffin toward the political left, did not drive him away from Christianity and belief. We don’t need to automatically assume it had that effect on us.

The political upheavals of the ’60s, in fact, may have impacted individuals depending on what they brought with them. Two of our classmates came to similar deep faith from opposite reactions to the war. One reports: “…the writing of an application [for] conscientious [objector status]…[led to] an integral vision of non-violence that has continued to inform my life and professional participation in the Episcopal Church.” On the other (right) hand: “Yale opened to me new ways of thinking, which proved essential as I’ve tried to live a life of faith while…serving actively in the combat aviation arm of the Navy—participating in the lethal applications of national policy…while still championing the religious impetus of mercy, service, and peace.”

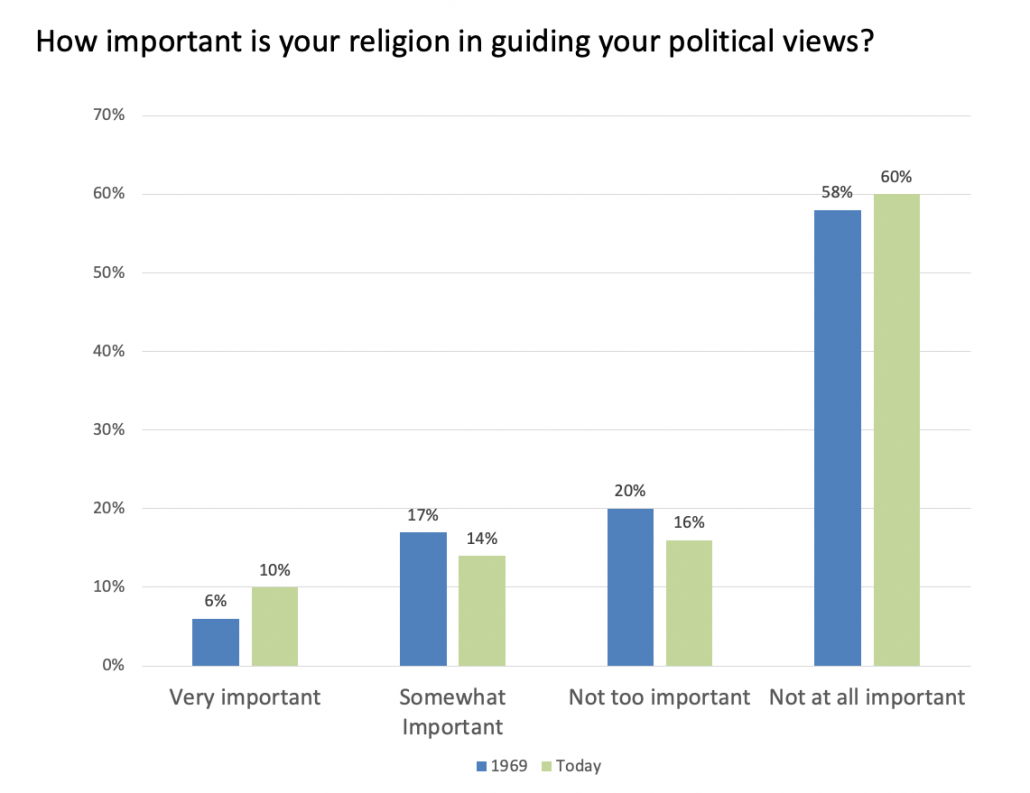

The class survey did not directly ask our class whether politics drove their spiritual views, but it did ask if religion drives politics. Mostly we think not: Figure 4 shows close to two-thirds of us denying that religion plays any part in their political views. Yet one has to wonder how much that’s a matter of definition. Probably few if any of us vote a particular way because the Pope or Billy Graham say so. Yet how can one’s outlook on eternal matters be unconnected with attitudes toward temporal ones? Classmates who say religion is “very important” in guiding their political views are a small minority, but doubled since 1969, mirroring the percent increase of those who find religion very important in their lives. And several of my interviews with men whose spiritual commitment has increased unhesitatingly said that this growth fueled changes in their politics. One of these men, whose day job is professionally observing and writing about political trends, says he sees this happening throughout his own religious group and others across the nation. One wonders if the influence is just not seen as such by those who don’t define their spiritual beliefs as “religious” but act as if there were a connection anyway.

A matter of definition—like everything?

A great deal of the change in our class, and in the nation in general, comes down to the definition of “religion.” Its use to mean a specific system of faith is relatively recent (13th-14th century). Cicero traced the Latin root word “religio” to “relegere” or “read again,” though he also defined it as “cultus deorum,” the proper performance of rites in veneration of the gods. Later writers connect it with “religare” (to bind tightly), others with “religiens,” the opposite of “negligiens.” These interpretations, much as they differ in details, have in common a sense of something objective or normative to be observed or performed—something outside oneself. That doesn’t necessarily imply insistence on “one true faith.” Imperial Rome happily accepted dozens of religions, so long as worshippers honored the emperor and paid their taxes; the various sects co-existed more or less comfortably. (The oddball sect called Christians were about the only people who had a problem with that.)

An increasing number of our class, and of the American people in general, seem to regard specified beliefs or creeds as irrelevant. One such articulates his belief thus: “The path to God consists of loving your neighbor as yourself. Any religion that teaches this doctrine…is [a] valid path to God…” Another: “The concept of what we call ‘God’ as a reality we can experience directly but never know completely (at least in this life). The experience is, I believe, universal, but is translated differently in each religious tradition, by each founder or prophet.” This may be a prevalent attitude even in churches espousing a highly traditional creed. One of our classmates ended an experiment attending the Episcopal church when he told fellow churchgoers he couldn’t honestly accept the Nicene Creed, only to have the Episcopalians respond, “Do you think we believe that stuff?”

Maintaining membership in a denomination while taking a relaxed attitude toward the denomination’s doctrines is at least in line with American religious tradition. Religion has always been regarded in the U.S. as a personal matter. The “establishment” clause in the 1st Amendment puts it up front: there shall be no government-sponsored religion and the government won’t interfere with anyone’s practice of faith. The unspoken corollary is that religion can exist in the public square without a direct effect on it. The three churches on the New Haven Green could be a metaphor: three different brands of Christianity, each with a slightly different set of beliefs, equally prominent in a shared public space but divorced from everyday life and government. Pretty revolutionary concept in 1787, given the tradition of state religion that was almost universal throughout Europe (including England) and much of the rest of the world. Even the French Revolution, with its superficial ideological similarities to ours, was far from faith-neutral; a driving Revolutionary principle was the eradication of religion and replacement with a sort of “religion of the state” (strikingly similar to the Bolshevik Revolution 150 years later).

“Spiritual but not religious”

It’s a small step from “religion is a personal matter” to “religion is what each person makes of it.” At its extreme, the emphasis on individuality produces the growing stance of “spiritual but not religious” (I’ll abbreviate that “SNR”—don’t try to sound it out). SNR has grown more than any other self-description, representing 15 percent of our current beliefs. Nationally SNR is a rapidly growing category, too. In fact, this is the one self-description where we’re pretty much in line with the country. The most recent Pew study shows “spiritual but not religious” responses in 2017 had gone up eight points in five years, to 27 percent. If you back out roughly 60 percent of that number who still identify with a particular faith (our Survey excluded those) you’re at about our level. College grads in the Pew study are slightly more likely to be SNRs, so you could even say we’re lagging a bit.

Being SNR is highly subjective, of course. “Spiritual” feelings can mean many things; recent neuroscience research at Yale found the same areas of the brain light up on fMRI scans during religious experiences, feelings of oneness in nature, and feeling “absence of self” during sporting events! But substituting introspection for neuroscience, one of our classmates defines it this way: “Spiritual but not religious…comes down to finding in oneself the Eternal Life that lives in everything, and experiencing that the Eternal Life that lives in oneself is the same.”

God Who?

Then there are the out-and-out atheists. “A simple faith, but a great comfort,” to quote science-fiction author Lois McMaster Bujold. Self-defined atheists have doubled since 1969, though they represent only about a third of those who say they don’t believe in God (which also includes agnostics and “others”). The “true unbelievers,” to misquote Eric Hoffer, defend their unfaith quite vigorously. One such describes his journey from mainline Protestant:

…at Yale my religious practice ebbed almost immediately…I finally “came out” at about age 50…an avowed atheist. Science, fact, reason, were at the core of my education and of my belief system. I rejected religious faith, miracles, and dogma (religious or otherwise) of all kinds…I look at myself in the mirror and say, ‘I don’t know exactly how it all began–yet, and that’s OK.’ I answer Pascal’s Wager with [Sam] Harris’ sarcastic rejoinder. What if I believed there was a diamond the size of a refrigerator in my backyard? What if this belief gave my life meaning?…I would be certifiable!

The metaphor is, of course, a snarky takeoff on Blaise Pascal’s famous “Wager” about the existence of God. Pascal posited in his Pensees that (to oversimplify), although we cannot know whether God exists, we should live as if He does, because if we believe and He does not exist, we have lost nothing, but if we don’t and He does, we have lost everything. The actual text is a lot more complex than that, starting with the fact that it’s as much about decision theory as anything else—Pascal was, after all, a great mathematician as well as a theologian. And as an exercise assuming that God’s existence is a matter for using probabilities to assign values to outcomes, the Wager really doesn’t apply to atheists or anyone else who thinks he already knows whether God exists or not.

However, Harris’ atheistic apologetic does energetically articulate where a lot of our classmates have wound up. Science, materialism, modern thought, and not inconsiderably their Yale experience, all pull them into the feeling that if there is anything more to life it’s unknowable at best and just not something to spend time and resources on, unless occasionally to meditate or contemplate the unknowable. And they’re all right with that—at least they think they are.

Looking back, looking ahead

The point about the “refrigerator-sized diamond”—or God—giving life meaning raises a final question about what one might call the utility of belief. Are believers more or less happy than unbelievers? The last section of our class survey asked about satisfaction with our lives and our outlook on the future. Results of the two questions are summarized below.

| How satisfied are you with the way your life has turned out? | How do you feel about your future? | ||

| Very satisfied. | 39% | The best is yet to be. | 10% |

| Pretty contented. | 42% | Still some things to do and accomplish. | 69% |

| Wish I could do some things over again. | 18% | It’ll be OK but don’t expect much new. | 14% |

| I think I messed up. | 1% | What do you expect? I’m a septuagenarian. | 7% |

Figure 5: Satisfaction with life and feelings about future [percentages rounded]

Overall, we’re a pretty cocky bunch (at least, those of us who made it this far). Over 80 percent think life has turned out pretty well. A similar percentage is optimistic about the future, albeit a more qualified optimism. Against that background, do crosstabs indicate that believers are any more content than doubters? With regard to the past, no. Comparing “absolutely certain” and “fairly certain” responders with “not very” and “no,” five times as many in each of the two groups pick the two most positive choices on the satisfaction question as pick the negative choices.

When it comes to the future it’s a different story. Unbelievers today are only half as likely as believers to say, “The best is yet to be” or “Still some things to do and accomplish.” Does faith generate confidence, or does confidence generate faith? Whatever the flow of causality, very few of either group throw up their hands and say, “What do you expect? I’m a septuagenarian.”

We all stand, on this golden anniversary of our graduation, peering into the future while reflecting on the past. That’s true through the outlook of any discipline, whether history, sociology, science, or what have you. But seen through the lens of religion and spirituality, “the future” can mean eternity. So, this is either the most meaningless topic in the world—or the most meaningful in the universe.

It is easy to look at today’s trends in the US and abroad and see us on the cutting edge—everyone is changing faith, losing faith, redefining spirituality, but we did it first and have done it more. In this view, generations that follow may look back on the Class of ’69 and call us prophets (albeit prophets whose words “are written on the subway walls”). Our class was at the tipping point of change: admissions criteria, grading, activism, co-education. Naturally we also led the movement to abandon outworn creeds.

But I wonder. Of course, as an Orthodox Christian I am biased, believing in a God who invented history, inserted Himself physically into history, and will come to abolish history in His own good time. But also as an (admittedly amateur) student of history and geopolitics, I’m aware of other times throughout history—some of them pretty recent—when faith seemed to hit rock bottom only to rebound. The restoration of the church after the French Revolution comes to mind, as do the “Great Awakenings” in this country (at least three, one for each century there’s been an “America”). And more recently, the ultimate defeat of institutionalized atheism in the Soviet Union and the return of entire nations to traditional worship (in Russia, since 1991, three new churches have been built per day, for the most part by the people, not the government).

Might future class historians identify as harbingers of the future not the 37 percent of us who declare “There is no God” but the 18 percent who say, “Definitely there is”? Might they say: “That was the low point, from which the Fourth Great Awakening was born?” Might they take these words from one of our non-theistic classmates—“Rationality alone does not suffice to tell you how to live. There is something bigger that calls us to something beyond.”—and add “That something bigger turned out to be, simply, God?”

To the atheists among the Class of ‘69, here’s a twist on Pascal’s Wager for you. If you’re right, we’ll never know the answer to those questions. If I’m right, maybe I’ll get the chance to say: “I told you so.”

Mike Baum (’69 TD) majored in English and Glee Club, then spent a checkered career in management and consulting, the last 25 years of which have been mostly with organizations serving pre-K-12 education. Along the way he has written on a number of topics, including some contributions to Touchstone: A Journal of Mere Christianity. He and his wife of 40+ years have three grown children and worship at St. George Orthodox Christian Church in Spring Valley, Illinois. Mike wishes to thank those who contributed to this essay through interviews, emailed comments, or just putting up with him as he researched and wrote it.

Great work, Mike!

Very interesting and thoughtful essay.

Geoff

Mike:

Many thanks for putting together this fascinating essay. Hope to pursue the exchange at our reunion.

Rusty Park

When people ask me if i believe in God, I always answer “depends on what you mean by “believe” and what you mean by “God”. There are many answers to this question.” I gave a drash (sermon) recently with some of the alternatives and my personal definitions.

don lewis

Thank you. Very informative essay, with a nice touch in relating the personal and the sociological.

First rate job, Mike… intellectually stimulating and strangely moving, actually. Maybe I’ll note here that my wife & I are Jewish sabbath-observers, and if other classmates share our practices, I hope we can get together for Shabbat meals. Last time (at the 45th) we shared Shabbat with Joe Lieberman, ’64 (who was there for his 50th).

Clearly, you proved more than up to the challenge of digesting, synthesizing, analyzing and — most importantly, explaining — our classmates’ responses to the survey. Thank you for taking on that task.

Michael, your review of this topic was comprehensive, well written, and totally fascinating. Excellent work! Having been a physician on the front lines of patient care for 46 years (not counting my four years at Yale Med School), my faith in God has grown stronger and has profoundly influenced how I have cared for so many here in rural eastern North Carolina. Without that faith, I really do not know how I could have dealt with all that I have seen over these years. Whereas many of my peers have burned out of medical practice long ago, having the deep seated belief that I was doing God’s work not only sustained me in practice but also a practice conducted with great optimism and with gratitude every day that I had the opportunity to help others in this way.

Thanks, Michael. I think that we sang together in Freshmen Glee, and at the time I gave little thought to the last names/religious affiliation of my classmates. I always identified and was proud of my Jewishness; after Yale, I answered a still small voice within to explore who I am as a Jew and where I come from, a relationship that is as compelling as ever. I look forward to reconnecting with all you mates–classmates, that is–at the Reunion.

L’hitraot–until Reunion time!

Mike,

Thank you for the careful planning and many, many hours you have put in to study our responses and our lives with such equanimity and thoughtfulness—and for taking all the disparate colors you saw to paint the rich and rocky spiritual landscape of our class, whether or not we see life over the horizon.

I look forward to talking about all this (and lighter subjects too) with you and Ruth at the Reunion…and after.

Mike, excellent essay on our class and religion. You actually led me to an interest in this topic as I read the essay. I’m one of the SNRs (spiritual, not religious). I explored a good bit in the human potential movement some years ago (EST, Actualizations, Living Love, Esalen) and I continue to have an interest in the occult area of spirituality (Edgar Cayce, et al). I found that there is a passion in spirituality as well as a meditative peace. What SNR lacks is a community of interest.. at least for me. In that regard, I long for the comfortable community I experienced growing up in the Presbyterian church. So Yale is really #1 in Jewish proportion of the student body? That’s just so interesting. I’ve come to greatly admire the Jewish culture acceptance and practice of peaceful but honest argument, a practice I find very lacking elsewhere. I look forward to seeing you at the Reunion. Herb