The Meaning of Yale for the Class of 1969—One Man’s View

[Originally published on 26 May 2019; This is third in a series of re-published Essays from the 50th Reunion ClassBook.]

Why is it that the four years from our arrival at Yale early in September 1965, to our graduation on June 9, 1969, have proven so important to so many of us? Most of us will be seventy-two years old in 2019, the year of our fiftieth reunion. Those four years we spent in college constitute a mere one-eighteenth of our lives. Why so important? Why is it that today you can initiate a conversation with a classmate with whom you may not have spoken in a half-century, and it will be as easy to talk to him as it was when we were undergraduates together?

I.

One reason is the set of events that took place outside the college’s hallowed halls. These included preeminently the Vietnam War and the upheavals of 1968, especially the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr.

The Vietnam War escalated while we were in college. Unlike World War II, this was not a war about which one could feel proud. Unlike the Korean War, Vietnam seemed endless. There were no “fronts” as there were in previous wars. The definition of victory was unclear and therefore its achievement uncertain. One soldier (not a classmate) was particularly eloquent: “What am I doing here? We don’t take any land…We just mutilate bodies. What the fuck are we doing here?”

The Vietnam War escalated while we were in college. Unlike World War II, this was not a war about which one could feel proud. Unlike the Korean War, Vietnam seemed endless. There were no “fronts” as there were in previous wars. The definition of victory was unclear and therefore its achievement uncertain. One soldier (not a classmate) was particularly eloquent: “What am I doing here? We don’t take any land…We just mutilate bodies. What the fuck are we doing here?”

Nevertheless, the promise of victory was constantly reiterated and just as often not achieved. In a word, the war was a bloody, pointless mistake. It was a horror. Everyone knew this except the policymakers in Washington. And even when they figured out that the war could not be won, they did not go public with this conclusion. They kept feeding young Americans into its maw. Many of us felt that Muhammad Ali was right to resist. “I ain’t got nothing against them Vietcong,” he said.

What did the war mean to our class?

First and most obvious, Yale—“Mother Yale”—kept us safe. We all had student deferments. Yale kept us from killing and—let’s face it, more important to most of us—from being killed as long as we were pursuing a degree in good standing. Over 58,000 Americans were killed in Vietnam, a lot more wounded, and some are still living with PTSD. We were different. We got a four-year “hall pass.” Nevertheless, some of us did fight in Vietnam after graduation.

Second, the flipside of the coin was that if you left Yale, you ran the risk of winding up waist deep in the rice paddies. “Here today…Punji stuck tomorrow,” in the words of one of our classmates. The price of leaving Yale could be your life.

Third, the drumbeat of this first “living room war” with its napalm and body counts was with us constantly during those four years. It forced us to face some uncomfortable questions. Were we patriotic? If so, what were we doing in New Haven while less fortunate Americans were in Pleiku, Da Nang, Khe Sanh, or some other dreadful place? If we opposed the war, why weren’t we as vocal about it as our remarkable chaplain, William Sloane Coffin, was? Some of our professors led teach-ins. Harry Benda comes to mind in particular. Others marched in protests or campaigned for candidates who promised to end the war.

Fourth, the war meant our class stayed together through those four years. The war was the external pressure that united us. We all had to come to terms with it. We all had the war in common.

II.

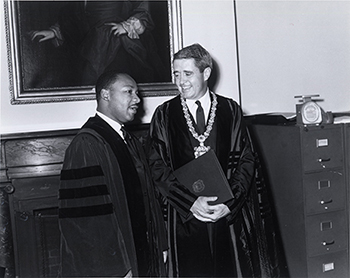

It was on April 4, 1967, that Martin Luther King, Jr., delivered one of the most courageous speeches any American ever did. The place was Riverside Church in Manhattan. The speech was titled “Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence.” King called the conflict what it was: a colonial war. He knew his public opposition to it would cost him support. But the war was evil, and he felt he had no choice but to oppose it publicly. Precisely one year to the day following that speech, King was murdered in Memphis, Tennessee. The most eloquent spokesman against the numberless injustices visited upon the black race in United States was dead. He was thirty-nine years old.

It was on April 4, 1967, that Martin Luther King, Jr., delivered one of the most courageous speeches any American ever did. The place was Riverside Church in Manhattan. The speech was titled “Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence.” King called the conflict what it was: a colonial war. He knew his public opposition to it would cost him support. But the war was evil, and he felt he had no choice but to oppose it publicly. Precisely one year to the day following that speech, King was murdered in Memphis, Tennessee. The most eloquent spokesman against the numberless injustices visited upon the black race in United States was dead. He was thirty-nine years old.

Riots broke out around the nation. New Haven was no exception. It was impossible not to hear the sirens of police cars zooming past the co-op toward Dixwell Avenue. It was a nightmare come true.

If you were taking History 42B, the history of the modern Soviet Union, your instructor was Professor Firuz Kazemzadeh, a Russian-born son of a Persian diplomat in Moscow. Professor Kazemzadeh was an expert on Iranian-Russian relations, and for a time he was the master of Davenport College. He was also a leading figure in the Baha’i faith.

The day after the assassination, Professor Kazemzadeh put aside his notes for the scheduled class. He talked about King and all he meant. It was clear from his touching, heartfelt remarks that King’s murder was a tragedy for the nation and for the world. One knew, although he did not say it, that Professor Kazemzadeh experienced King’s assassination as a personal loss. A lot of education took place that day.

On April 26, 2017, Professor Kazemzadeh wrote, “In spite of my advanced age, I clearly remember the day after the assassination of Martin Luther King…[but] I have not given up my conviction that in spite of all setbacks, humanity is progressing towards the abolition of racial and nationalistic prejudices.” Three weeks after he wrote these words, Professor Kazemzadeh died. He was ninety-two.

Do we have the courage to share Professor Kazemzadeh’s optimism? Courage and faith are what it will take because of the state of the world today.

Martin Luther King, Jr., was irreplaceable. His murder stole from us a true leader. “Leadership” is a word often used, but the phenomenon is all too rarely encountered. King’s death cast a pall over 1968, which turned out to be a very strange year indeed.

Just a week before King’s murder, on March 31, President Lyndon Johnson delivered a televised address to the nation. Somehow, a lot of us knew that something big was up because we watched the speech on television. Johnson concluded with the altogether startling declaration that “I shall not seek, and I will not accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your President.” Johnson was fifty-nine years old when he gave that speech. He looked like a man in his eighties. That evening, you could not place a call to Washington from New Haven. The lines were overloaded.

The true reason behind Johnson’s decision will never be known. We do know that Senator Eugene J. McCarthy of Minnesota had decided to challenge him for the Democratic Party nomination in 1968. On March 12, New Hampshire held its primary. McCarthy, aided by a cadre of college students some of whom doubtless were our classmates, received 42 percent of the popular vote. Johnson won the popular vote with 49 percent, but McCarthy’s showing was unexpectedly strong, illustrating the unpopularity of the war and of Johnson personally.

Four days after this contest, Robert Kennedy took the opportunity to enter the race. He realized that Johnson was vulnerable.

To recount all the twists and turns of politics in 1968 would take a book. It is probably true, however, that no year in living memory saw college campuses so politicized.

On June 4, Robert Kennedy was assassinated. That left the nation with two presidential candidates, Richard Nixon and Hubert Humphrey. Neither man was truly anti-war. Neither had a grain of charisma. Both were retreads.

Nixon’s nomination was secure. Humphrey was formally nominated at the convention of the Democratic Party in Chicago in late August. That convention was literally a riot. Many college students, including members of our class, were there. It was an inauspicious prelude to our final year in college.

The election itself was an anticlimax. However, the results were more significant than most of us imagined they would be. There was more killing in Southeast Asia after we graduated than while we were at Yale. The pity, one might say the tragedy, of the flat conclusion of Johnson’s Presidency was the blotting out of the magnificent domestic legislative achievements he engineered in 1964 and 1965. Chief among these were the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act. This legislation constituted giant steps toward doing something about the institutional racism in the nation. Indeed, these two acts are still resisted today by American racists.

III.

III.

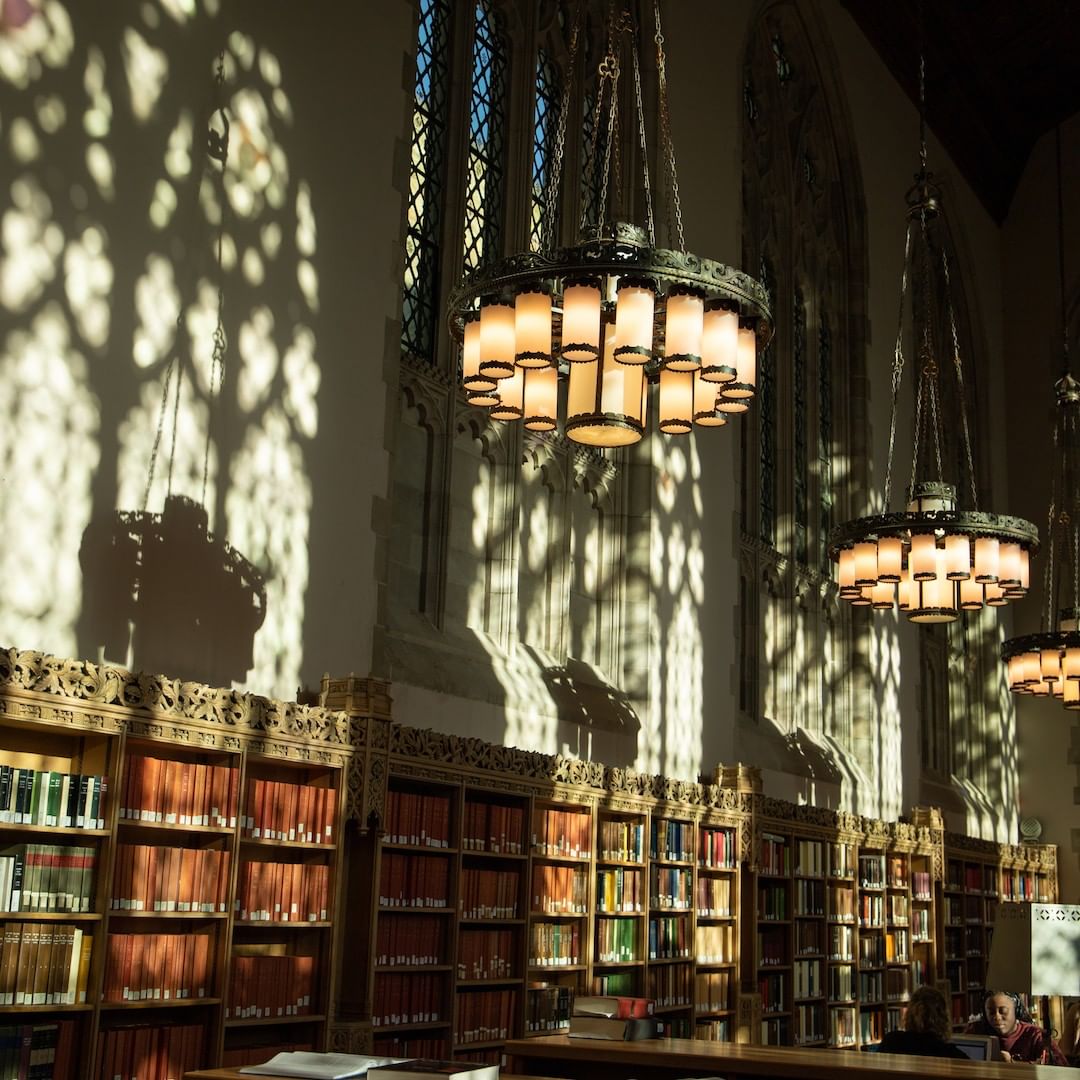

Such was the tumultuous world outside. Inside Yale, fundamental changes were a-foot during our bright college years, changes which would forever change the college.

To be sure, there was continuity with the past as well. For example…

Yale was a four-year experience with very little transferring in or out. It was an on-campus experience. Few people lived off- campus during those four years, and few were married prior to graduation. Indeed, there was not much transferring from one college to another. The result was that we spent a lot of time with our classmates. Some of us formed bonds that have endured for half a century.

Those four years were marked, as they must also have been for many an “old blue” who preceded us, by a search for companionship. In one way, that search was more easily satisfied than it has ever been since we left. Any time of the day or night, you could knock on any door and get into an interesting conversation.

No one had to be bored at Yale when we were there. Nor hungry. If you needed a great burger, the Yankee Doodle was a stone’s throw away.

Female companionship on the other hand—that was a different story.

We chose Yale full in the knowledge that it was not co-educational. Now this seems ridiculous; but at the time, it did not seem strange at all. Many elite eastern colleges did not admit women. Many of our classmates had attended all-male private schools, so the idea of single-sex education was not novel.

And if, prior to selecting Yale, a prospective student asked about the absence of women, the response was reassuring. Girls were easy to meet. They’d visit Yale to get their MRS degrees, and Yale men were a valuable commodity. As the song goes: “Though we have had our chances for overnight romances with the Harvard and the Dartmouth male. And though we’ve had a bunch in tow from Princeton Junction, we’re saving ourselves for Yale.”

Suspicions should have been raised when we found on our doorsteps freshman year a questionnaire prepared by “Operation Match,” the first computer dating service in the United States. You answered the questions, submitted the form, and received a list of girls with whom to get in touch. At least that is how it was supposed to work. Your faithful author tried it. I got the names of nine women and one man in return. The man—he literally live next door to me in Vanderbilt Hall—had checked the wrong box for his own gender.

More disturbing and revealing for anyone who saw it was a fifty-seven-minute documentary commissioned by Yale itself entitled “To Be a Man.” The film was shot our freshman year, picked up by public television, and aired on sixty stations across the nation.

It is a poor excuse for a documentary (in my view, for what that may be worth) that manages to be both boring and terrifying at the same time. Most terrifying is the complete absence of women. There is merely one brief shot, twenty seconds long, of a woman. She is shown being filmed by a man, probably for a class assignment. We do not even see her face. She is a prop. That’s it for the opposite sex.

No women are seen in class, either as students (obviously) or as teachers, and no women are seen talking to a Yale man outside of class. Indeed, no woman is mentioned in the whole depressing documentary. If women were in fact saving themselves for Yale, they were very disciplined about it.

The complete absence of women is experienced not merely as an oversight or as a blank page. The film conveys the impression that women simply did not exist. They had disappeared into an Orwellian memory hole. The film is a lie, because the truth is that finding the right girl was one of the magnificent obsessions of many of us during our four years at Yale.

Mixer after dismal mixer, blind date after dismal blind date, the search was fruitless for many of us. But no matter how many the disappointments, the yearning did not disappear. If anything, it grew.

Yale gave us so much. A truly great education. The College, Kingman Brewster always said, was the center of the University. Think of spending next term taking courses taught by Robin Winks, Edmund S. Morgan, Robert Dahl, Vincent Scully, and Harry Benda. For most of my own professional life, 31 years, I was a member of the Harvard faculty. Please believe me when I say that no one would allege that the college is the center of the university there.

Yale gave us friends, a network, a great brand, and so much else. But it deprived us of the opportunity to interact with women as our intellectual equals. For too many of us, women were sex objects; and the only trait that really mattered was their looks.

The saddest tale we have to tell is that there were no women in our classes. The realization that their absence was an injustice to both genders and that Yale had to change came from us. Our classmates engineered co-ed week–-from November 4 to November 11, 1968. For all Yale gave to us, coeducation was a gift we gave to Yale.

Ours was the last class during which Yale was an all-male college. From 1701 through 1969, it was for men only. That changed forever the following year, and that change is greatly to be celebrated.

The classes after us surely have negotiated difficult issues of gender and gender-based relationships. But an all-male Yale they have been spared. Our class played a major role in persuading the university to transform itself. We each paid a price for the exclusion of women (not to mention for the matriculation of but a small number of minorities); but at least we helped the next class avoid the same experience.

For many of us, sexuality was mysterious; and our experience as undergraduates did little to dispel that mystery. Some of our classmates—and professors—yearned not for women but for other men. There was little if any open, serious discussion of homosexuality at Yale during our years. Most, not all, of us learned that some of our classmates and instructors were gay only after graduation. And sometimes we only learned after tragedy—AIDS in the 1980s—struck.

IV.

From 1965 to 1969, there were major changes in the grading system and in the course load at Yale.

When we arrived, we received numerical grades. Under 60 was failing. The average grade in our class for the first term freshman year was 79.

Numerical grades lasted through sophomore year but stopped there. They were replaced by a system with four categories: honors, high pass, pass, and fail.

The course load was also reduced. We took five courses per semester freshman year. We were only required to take four senior year.

These changes did not result from student pressure. We simply accepted them. To be sure, some of the courses were very demanding of one’s time. Most of the hard sciences, Chem 29 for example, were really difficult. You received a grade both for the course and for the lab.

Some of the courses in the humanities were time intensive as well. For example, English 24 (if memory serves), “The Epic and The Novel,” began the second term with the three chest crushing volumes: Don Quixote, The Brothers Karamazov, and Moby Dick. You covered those books, amounting to over 2,500 pages of reading, in six weeks. If you had four other courses with similar assignments you found yourself responsible for close to 2,100 pages of reading a week. So, trimming the course load from five to four may not have been unreasonable.

However, it can be argued that both the changes in the course load and the grading system were unfortunate. The fact that we survived two years with five courses a term means that we could well have survived the same load for another two years. And we would have taken four more terms of courses.

To be sure, there was no rule that you had to take four courses. You could have stayed with five for the last two years. But now that we are old, it is easy forget how competitive we were in those days. Many of us were headed for graduate education. If you wanted to get into the best school, you had to have the best record. Taking on extra work was not a clear avenue to that goal. Thus, many of us short-changed the classwork and spent our time elsewhere. In the five decades since, we have learned that the world of work demands a great deal more than college. For all the anxiety, it was an easier time.

As for the change in the grading system, it was problematic. A continuum was transformed into a step function. High pass was meaningless, and few of us were failing courses by junior year; so, the new system amounted to two grades: honors and pass.

It is difficult indeed to provide a numerical grade for a course in the humanities and in most of the social sciences. What is the difference between a 78 and a 79 on an essay on T.S. Eliot’s “Gerontion”?

Though this is difficult, it is not impossible. Whoever got that 79 wrote a better paper than the recipient of the 78. More important, a college owes its students a genuine evaluation of their performance no matter how difficult it may be to arrive at one. Did the new system serve that purpose?

V.

Other changes were taking place as our class wended its way through its four years. The trend was clear. It was in the direction of rebellion against the rules and norms of old.

At first, we were compliant. Parietal hours meant that you were not supposed to have a girl in your room past midnight. By senior year, Davenport, for example, was known as the Davenport Hilton. Women spent whole weekends in our rooms, and it was quite unremarkable to see them at breakfast on Sunday morning.

When we got to Yale, we were required to have our posture evaluated. This was accomplished by taking photographs of us naked with slender rods taped to our bodies. Did anyone object to this humiliating ritual?

We had 39 hours of required gym. After we were cleared of incipient lordosis or kyphosis, we had to pass various tests. These included 60 sit-ups, eight pull-ups, a fence vault, broad jumping five-and-a-half feet and jumping 20 inches high. Can anyone conceive of requiring such a regimen senior year?

We were expected to wear coats and ties not only to classes but to meals freshman year. That did not last long either.

By far the biggest transformation was around self–medication. We migrated from alcohol to drugs.

The legal drinking age in Connecticut in 1965 was 21, but that did not prevent anyone from imbibing whenever we wanted. A senior could always be prevailed upon to buy a bottle for someone not of age. And our classmates who owned cars could and did make a business of taking orders, driving to New York State where the drinking age was 18, and returning with a car full of alcoholic beverages.

Some of us had smoked marijuana prior to coming to Yale. Marijuana, still illegal in Connecticut but legal in a number of other states now, came to Yale later than it did to some California schools, especially Berkeley. Sophomore year, it was still more absent than present. Junior year, things began to change, depending on which residential college you lived in. If you were in Trumbull, you probably were smoking marijuana and hashish and perhaps had moved on to mescaline and LSD. In Morse, much less likely.

By our last year at Yale, marijuana was all over the campus. You expected it at parties. Where it came from was not at all clear. Nor was it clear who paid for it.

What was clear was that getting stoned and getting drunk were different experiences. The cultures of the two were different. The iconic image of drinking was Humphrey Bogart’s Rick, sitting alone, getting drunk after encountering Ingrid Bergman’s Ilsa in “Casablanca.” Marijuana tended to be a social experience. You passed a joint around from friend to friend while listening to dreadful music and convincing yourself that it was profound. And you did not wake up the next morning with a hangover.

Marijuana heightened–or at least was perceived to heighten–the senses. Chief among these was taste. People who “toked up” regularly began to put on weight. Especially appealing, it was said, were foods that had different textures in a single bite. Ice cream sandwiches stocked out of vending machines across campus. And it became difficult to find fig newtons in food stores.

VI.

There was a good deal of division among us during our four years in college. Not everyone approved of the drug culture. Some of us were racists. One of our classmates had a “White Power” sign prominently displayed in his window so that everyone walking into his college saw it. Not everyone approved of the politics of William Sloane Coffin. A lot of us who opposed the Vietnam War also opposed those whose opposition was most vocal.

When Columbia blew up in 1968, many of us were appalled. Harvard students staged a “sit-in” at University Hall, one of the oldest buildings on the campus, on April 9, 1969. They were violently evicted by the Cambridge police the next day, provoking profound controversy within the university. (Yale was shut down after we graduated, in the spring of 1970.)

There was no such sit-in during our years at Yale. When a Harvard student came down to New Haven from Cambridge to rally support, he delivered a fiery speech standing at the corner of Woolsey Hall and Commons. After talking about Harvard, he said, “Now let’s talk about Yale.” The students there spontaneously broke into “Bulldog, Bulldog, Bow Wow Wow.” The door to Woodbridge Hall was conspicuously left open. There were rumors of a “baseball bat squad” composed of athletes that was prepared to evict any students sitting in at a Yale building, saving the New Haven police the necessity of doing so.

With all this division, there was one matter on which everyone seemed to agree. Everyone–interested in sports or not–was a fan of our football team.

Why?

There was something Homeric about that team. The team’s equivalent of Homer was Gary Trudeau. Everyone followed “Bull Tales.” Everyone enjoyed it. When Trudeau, a year behind us, asked Reed Hundt, Executive Editor of the Yale Daily News, if the paper would print his cartoons, he said, “They’re all right. We publish pretty much anything.” “Bull Tales” premiered on September 30, 1968.

The team was a joy to watch. Game after game, there was an aesthetic pleasure seeing them in action. And these great stars, who made the front page of Section 5 of the New York Times Sunday after Sunday, were both our heroes and our friends.

The first two years we were at Yale, the football story was pretty grim. Three and six in 1965. Four and five in 1966. Fifth in the Ivy League both times. Shut out by Harvard both years.

In 1967, the team, after an inauspicious beginning (a 26 to 14 loss to Holy Cross), won every other game and by fantastic scores. The only close call was the 24 to 20 victory over Harvard. 68,315 people saw that game in the Yale Bowl. It was Yale’s first Ivy League championship since the undefeated, untied team of 1960.

Yale and Harvard were both undefeated and untied when they met before 40,280 spectators at Soldiers Field in Boston, just over the Charles River from Harvard’s main campus. It was the first time these two teams had faced each other undefeated and untied since 1909. A college coach many years ago said that a tie game was about as exciting as kissing your sister. He was wrong.

Yale led the whole game, until the final 42 seconds. Harvard scored 16 points in those seconds. The Harvard Crimson’s justifiable headline was “Harvard Beats Yale 29– 29.” It hurt.

But since this essay is supposed to be about “meaning,” is there any meaning to be found in what at the time was experienced as a wallop to the solar plexus? Outside the stadium, people were collecting funds for Biafra, part of Nigeria which was trying to secede and become an independent nation. Almost two million Biafran civilians died in this attempt. And we were unhappy about a football game?

Perhaps we were foolish. But we had witnessed something that seemed both inevitable and unjust. All the standard sports clichés-–“It isn’t over till it’s over”–apply.

But somehow that game was difficult to decode. We saw that endings are not always happy . . . that life can play dirty tricks, that endings can be cruel. A tie. What does one make of that? Despite everything, most of us were proud to be Yale students. We thought the future was ours to grasp. Then we saw our beloved team lose a tie game. Nothing good is guaranteed.

Decades after that game was played, I found myself talking about it with one of the team’s outstanding players. He was on the field during those final, wretched 42 seconds. I remarked that the outcome was so terribly unfair. Yale was clearly the better team.

His response captured the meaning of that day as well as anyone has: “The better team is the team that wins on game day. That’s why they play the game.”

VII.

June 9, 1969. Graduation. Or commencement as it is called. And commencement is a better word. We were merely at the starting gate. September, 1965, to June, 1969, was before the beginning. We learned a lot and grew a lot. But the truth is we didn’t know anything.

That day was a great day. Just enough pageantry to connect us with our predecessors. But not too much to be phony. We had a chance to tip our mortarboards to Kingman Brewster, perhaps Yale’s greatest president. And we listened to some of our classmates give a couple of genuinely outstanding addresses.

Some of us had a pretty good idea of what we wanted to do. Many of us were undecided. Some of us had met the women who would be our life partners. Many of us had not.

The fissures in the class were quite present on that day. One of our classmates, addressing not only us but our parents, said of the war that “Face is expendable. Lives are not.” One of our classmates in the audience said, “That’s not true.” Was it? Is it?

We were launched upon the earth to spread light and truth. Did we? At orientation in September, 1965, Kingman Brewster told us in Woolsey Hall that Yale graduates a thousand leaders. Did it? Have we fulfilled our destiny?

Now we are old and face the sunset. If our four years at Yale were really before the beginning, are we now, at 72 years of age, after the end?

Tennyson, in “Ulysses,” wrote:

Old age hath yet his honour and his toil;

Death closes all: but something ere the end,

Some work of noble note, may yet be done,

Not unbecoming men that strove with Gods.

To be at Yale with all of you was the privilege of a lifetime.

Each of us remembers those years through the lens of our

own lives. We were searching for meaning. That search

never ends.

(The following are responses to this essay from Tom Guterbock and Bob Sussman)

Richard,

Thank you for sharing your powerful essay on the meaning of our Yale experience and allowing me to comment. There’s much that I like about what you’ve written, but some things hit me wrong. I think there are some important things about our experience as a class that you haven’t fully captured.

The most important thing is that, while our class attended Yale during a time of turmoil and massive change, we were (as I see it) more on the trailing edge of the Old Yale than we were on the cutting edge of the new. It was the class of ’70 that really rebelled. We DID all dutifully go for our posture pictures and body building. We DID wear our coats and ties to meals (it was after our departure, I believe, that the dress code for meals was lifted.) The class of ’70 just said “hell no” to the pictures. And the ties. A key memory for me was attending a huge meeting, including students and faculty, at Ingalls Rink to debate whether ROTC should be discontinued at Yale. (Probably in ’68, I’m not sure when.) A vote was taken, and the outcome was a tie (900+ vs 900+ against, I think)—an absolute, dead tie of a vote, which forestalled further pursuit of that proposal. Take a good look at our yearbook, how we dressed and wore our hair: there were precious few of us who looked like hippies. We had bought into the idea of Yale as “mother of men” and to many in our class it didn’t seem wise, or in our interest, to tear down every tradition. Yes, a few of us went on to the teacher corps or the peace corps or to lives of activism, but most of us went into the traditional fields of the elite (law, medicine, education, engineering, finance, business).

Your essay plays up the efforts of some of us to change things and respond to the protest and countercultural movements of the time, and in places you do acknowledge the diversity of viewpoints and experience. But I was put off, personally, by your strong criticism of the Vietnam War at the top of the essay. Setting aside the issue of how your view might differ from mine, then or now, I would urge you to take a look at the results of our class survey. We were divided. Here’s what our classmates report about how they presently view the war: 6 percent think it could have been won but we lost the political will to win it, five percent say it was not immoral, but we fought the war the wrong way, 39 percent say it was a mistake but NOT immoral.

So, only about half of us (47 percent) currently agree with your view that it was both immoral and a mistake. But look at what we recall thinking about the war in 1969: back then three percent saw it as a “noble cause,” ten percent just thought it was fought the wrong way (neither immoral nor a mistake), 45 percent saw it a mistake but not immoral, and only 39 percent say they saw it as immoral at that time. That is, about 60 percent, back then, rejected the view of the war as being immoral.

The survey also reveals that about 25 percent of the class did go on to serve in the military, one way or another: three percent were drafted and served, 14 percent volunteered for active duty, and another 7 percent (myself included) joined the National Guard or reserves.

I’m not trying to argue that the class as a whole was conservative. But most of us were liberal in a fairly cautious way, and the real radicals among us were viewed as, well, real radicals, out of the mainstream. Here’s our characterization of our overall politics then:

Liberal vs. Conservative (1969)

| Frequency | Valid Percent | ||

| Valid | 1 Extremely liberal | 106 | 18.6 |

| 2 Liberal | 191 | 33.5 | |

| 3 Slightly liberal | 85 | 14.9 | |

| 4 Moderate | 84 | 14.7 | |

| 5 Slightly conservative | 41 | 7.2 | |

| 6 Conservative | 61 | 10.7 | |

| 7 Extremely conservative | 3 | 0.5 | |

| Total | 571 | 100.0 | |

Liberals are in the majority, but 48 percent are in the categories from “slightly liberal” to “extremely conservative.”

Going back to the essay: I think your vivid description of the wrenching events of our time is beautifully done, but you’re missing an opportunity to highlight the tension that existed between the calls for change coming from all around us and the loyalties so many of us instinctively felt to the ways of Old Yale. You get at this a little bit with the anecdote about the reception of the Harvard radical, but overall the essay reads as if most of us were committed to the change agenda of the left and to the lifestyle of the counterculture. Yes, I was one of the guys smoking dope in Silliman after the summer of ’67, I did volunteer briefly for Gene McCarthy in ’68, and some of my buddies at WYBC were into LSD and who knows what… but, overall, it’s not the Yale I remember. I would have wanted your essay to give voice to your views and experience while also making this tension more vivid. We were on the edge, and a lot of us acted as though we were afraid of falling off. And very few of us were “alienated”—we loved Yale and were brimming with pride to be there. Look at this result from the survey; 84 percent were mostly or very positive about Yale back in the day:

General Opinion about Yale (1969)

| Frequency | Valid Percent | ||

| Valid | 1 Very negative | 2 | 0.3 |

| 2 Mostly negative | 5 | 0.9 | |

| 3 Somewhat negative | 21 | 3.6 | |

| 4 Neutral | 14 | 2.4 | |

| 5 Somewhat positive | 50 | 8.6 | |

| 6 Mostly positive | 229 | 39.3 | |

| 7 Very positive | 261 | 44.8 | |

| Total | 582 | 100.0 | |

(BTW, the class is a lot less positive about Yale now than it was then. But that’s off topic.)

Another aspect of our time at Yale should also be highlighted: the amazing strength and vitality of the student organizations. I believe that was very much a product of our all-male composition. The OCD, WYBC, the Banner: these were all run like fraternities. You had to heel for eight weeks to get in, you got a tie, there were elaborate traditions in each of these, some of them intentionally degrading to the heelers. You can argue that this was all sublimated sexual energy because of the total absence of women on weekdays; or just a result of us having more time because we couldn’t socialize with women; and you can see the negatives in the systems of selection and exclusion that were part of that ethos. (Not to ignore the sexism and homophobia baked in.) But it was amazing to me, when I left Yale for U of Chicago, to see the cynicism, casual loyalties and disorganization of the student extra-curriculars there. I truly believe that extra-curriculars at Yale were stronger than at most places, and very probably stronger before coeducation than after. You touch on this by talking about individuals talking with one another in dorm rooms after hours… but the life in the organizations was vital and valuable, too. The absence of adult supervision in these organizations was also notable. They were student-run and mostly self-financed. A lot of them, like the student laundry, made money by preying on gullible freshmen. I doubt that situation would be tolerated today.

Obviously, this is your essay and you can say what you want. I didn’t know you at Yale, but reading your essay it sounds like maybe you weren’t that fond of organizational life and that you were more on the left than I ever was. In my view, to depict how it really was, one would need to highlight how torn we were as a class between our loyalty to a bastion of tradition along with our deep involvement in so many organizations that thrived so vigorously on an all-male, heterosexual ethos (on the one hand) and our sympathy for the powerful movements of change outside (on the other). Our class opened some of the gates of future change, but it was really the classes that followed us who stormed through those openings. Perhaps one way to capture that story would have been to differentiate more clearly between your own experience and the collective experience (or just diversity of experience) that is partly reflected in the survey results.

In closing, let me again express my appreciation for sharing with us, so powerfully, your take on what Yale meant and why it meant so much. In a private response to these comments, you shared with me a wonderful metaphor. You wrote to me: “Among the most important issues you raise is ‘trailing edge’ versus ‘cutting edge.’ Perhaps there is a middle term. Hinge or pivot.” I think that’s an inspired image that would work for you, for me, and for so many in the Class of ’69. As mostly-proud members of Yale’s last all-male class, coming of age as we did in those turbulent years, we experienced a crucial pivot point in our own lives and in the life of that great institution as well.

All the best,

Tom Guterbock, SM ’69

——————-

Richard,

You’ve taken on a difficult challenge and I applaud you. There’s an infinite amount to say about our four years at Yale and how they influenced the rest of our lives. Your draft is a good start. You provide a vivid overview of the historic events that marked our time at Yale—few alumni can say that their college years were as eventful and dramatic. However, much as we were witnesses to these events, there was a separate personal dimension to our Yale experience that is more important, if more difficult to capture. It involves the struggle to find ourselves as the ground was shifting beneath us because established values (and indeed the very meaning of a Yale education) were under attack after a long period of stability on campus and in American life. We arrived at Yale in 1965 at the end of two decades of conformity, national self-confidence, and upward mobility that followed World War II. We came from different backgrounds but the Eastern WASP culture dominated and it instilled an image of ourselves as fledgling members of the establishment being groomed for conventional success in law, business, academia, government and so on. Four years later, these smug expectations were in tatters and many of us were fundamentally unsure of what Yale was teaching us, how we would use it in our own lives and where we would land in a confusing and unsettled world. Obviously, this wasn’t true of everybody—many of our classmates knew exactly where they were going—but a striking characteristic of our class was the sense of self-doubt and accompanying willingness to venture off the beaten track in search of a more “authentic’ reality, be it the counterculture, eastern religion, rock music, drugs, radical politics, communal living etc.

The intriguing and difficult question is whether the personal upheavals we experienced in unsettled times were the normal and temporary if unusually intense growing pains of young adulthood or a more lasting transformation of values and life mission. An argument can be made for the former—after a few turbulent years, most of our classmates returned to the conventional trajectory of Yale graduates, leading orderly lives, pursuing the expected professions and succeeding by traditional standards, as several generations of Yale graduates had before us. Perhaps we were better people because of our college experiences in the ’60s but I wonder whether that is the case. As you observe in your piece, we managed to combine high-mindedness and selfishness by protesting the Vietnam war while avoiding the personal hardship of serving in the military. Even as rebels and critics of the establishment, we were elitist to the core, using our connections and knowledge of the system to protect our skins while working class whites and blacks bore the brunt of the war. Today, our personal views may be somewhat to the left but not dramatically so and I suspect that our class members are heavily represented in the top 1 percent. We may care about income inequality, racism, and the environment but (again with exceptions) we haven’t made personal sacrifices to combat them. And while we may have vowed to improve our country as newly minted graduates, the country hasn’t improved but, in many respects, has become worse. As the people in positions of prominence and influence, we bear some responsibility for that.

You asked about my own Yale experiences. I don’t know how to pigeonhole them. I was a Jewish kid from a troubled middle-class family who managed to go to a good public high school on Long Island. My admission was part of the effort of Kingman Brewster and Insley Clark to democratize Yale and reduce the influence of elite prep schools. I lacked the worldliness and amenities of the prep school crowd but that didn’t hold me back—I actually reveled in the new types of people I met and the expanded horizons that Yale offered. Both academically and socially, I soaked up the Yale experience. I worked very hard but did not feel much pressure. I played tennis, went to football games and road tripped to Vassar. The classical music scene at Yale was wonderful and I happily dipped into it. There were difficult moments but not many in comparison to my childhood and the years following graduation. I was politically aware and followed the news but wasn’t an activist. I steered clear of drugs except for occasional marijuana use and had a healthy skepticism of radical ideas (maybe because my parents were radical and it didn’t seem to work for them). I never felt alone or isolated and had a wide circle of friends. I went through the usual contortions to avoid the draft and attended a few Vietnam War protests but was more preoccupied with my own future than the upheavals around me. My biggest dilemma was whether to go to English graduate school or law school—Yale admitted me to both—but I chose the safer path of the law. I had vague aspirations to use my law school education for social betterment but, like others, lacked the willingness to take risks and opted for the world of top-tier law firms, a choice motivated by establishment values that I had absorbed as an undergraduate.

I wonder what you would say about your Yale experiences and the choices you made…

In any case, I’ve said more than I planned and hope it helps you as get feedback from others.

Hope all is well,

Bob Sussman, SY ’69

We’re given a single “like” button. Does that mean we have to like all three pieces or dislike them? Seems to me that the main piece, Tedlow’s, ought to have its own like button; and maybe the two long comments as well. I liked them all but the first one best. Maybe there should be grades instead of pass/fail.

Thanks Richard. Sorry we didn’t cross paths at the reunion.

We never met before our shared membership in an underground “spook”. Since you did not comment on secret societies in your essay, I doubt that was a key part of your Yale experience.

My few quibbles with your thoughts are not worth mentioning; it is just great to hear your ( very characteristic) “voice” again.