The Yale Daily News

excerpts with commentary

Although freshman year could have been justifiably regarded as an oasis of calm, our subsequent undergraduate years (along with 1970) probably constituted the most tumultuous period at Yale (and many other American college campuses) since World War II. The controversial and escalating Vietnam War, the prospect of compulsory service in it following our college careers, the fervent political activity to “dump Johnson” and end the War, the black (and to some extent) Hispanic civil rights movements, the rising counterculture, the earnest search for academic “relevance,” and increasing demands for coeducation at Yale (and other single-gender colleges) upended the carefree tranquility that tradition tended to associate with our “bright college years.” The staff of the Yale Daily News tried its best to report on the principal developments that affected the campus. What follows are stories of a few of them.

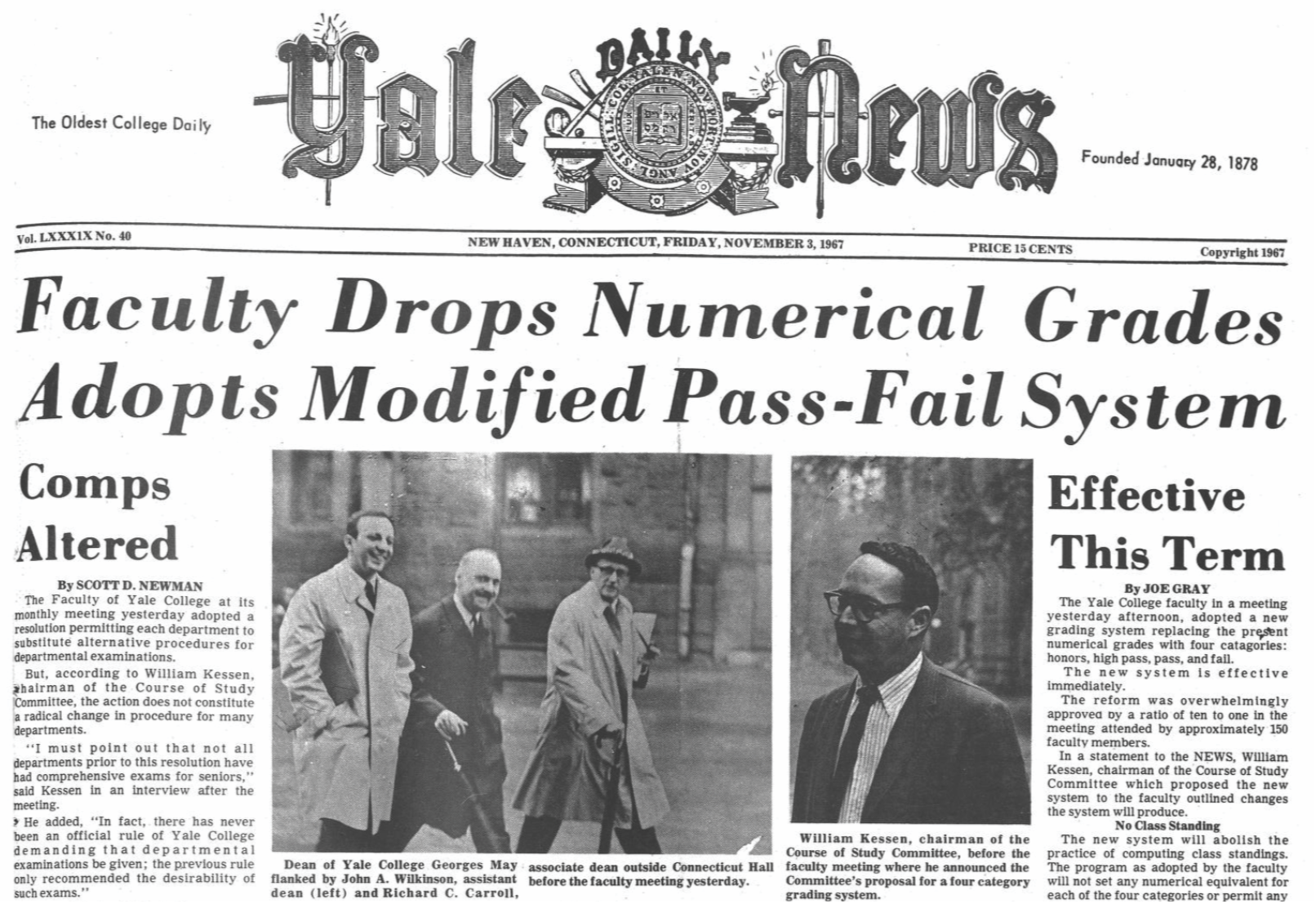

November 3, 1967

The decision by the faculty to abolish class rankings and numerical grades in favor of a much looser set of grading categories—honors, high pass, pass, and fail—was the first of a series of major changes to academic requirements. Subsequently, mandatory course loads were reduced, comprehensive exams were eliminated by many departments, and residential colleges were allowed to initiate and conduct their own seminars for academic credit—the so-called “Hall seminars.”

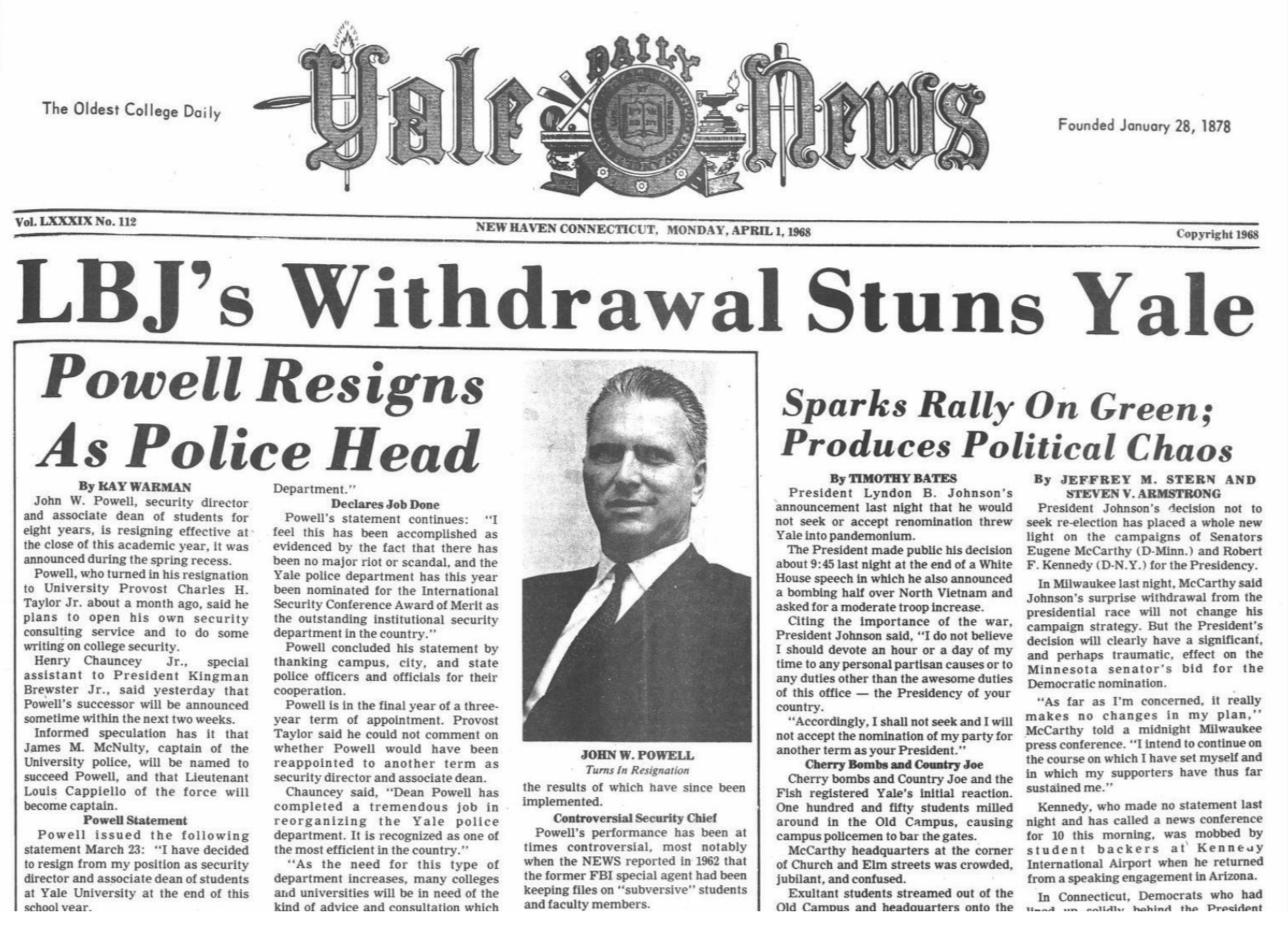

April 1, 1968

The intensifying Vietnam War (and the possibility upon graduation or other forms of departure from Yale of being drafted to serve in it) served as an increasingly intrusive backdrop to our “bright college years.” During the winter of 1967–68 many college students, including some from Yale, worked enthusiastically in New Hampshire for the candidacy of Senator Eugene McCarthy for the Democratic nomination for the Presidency. After McCarthy tallied a surprisingly strong result in the New Hampshire primary in early March and Senator Robert Kennedy then entered the contest for the Democratic nomination, President Lyndon Johnson dumbfounded the nation by announcing his withdrawal from the Presidential nomination process. However, despite fervent hopes to the contrary, his decision did not lead to a rapid conclusion to the war. During our summer vacation, the assassination of Robert Kennedy deprived the nation of its most prominent, anti-war presidential candidate.

April 8, 1968

The assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., the widely acknowledged leader of the black civil rights movement, shocked the whole country and precipitated civil unrest in many cities. Although that movement had succeeded in obtaining sweeping Federal civil rights legislation in the mid-1960s, many blacks remained profoundly dissatisfied about the persistence of discrimination and other grievances. Urban riots broke out in various places in 1967, and militant, black separation groups tried to seize the initiative from moderate integrationists like Dr. King. His assassination dramatically deepened racial tensions. New Haven and Yale remained fairly calm until the spring of 1970 when the local criminal trial of a black militant convulsed the city and shut down the campus.

April 24, 1968

It may have seemed peculiar that amidst the national upheavals a major student protest erupted over the Yale administration’s plan to perforate the lawn of the Cross Campus with rows of large, obtrusive skylights to illuminate a new library underneath. But given Yale’s glorious, architec- tural heritage, it was probably both appropriate and admirable that this proposal became the source of significant student agitation. Although away on a sabbatical, revered art history professor Vincent Scully lent his support to the student opposition. To its credit, the administration ultimately abandoned the skylights and built the library without them.

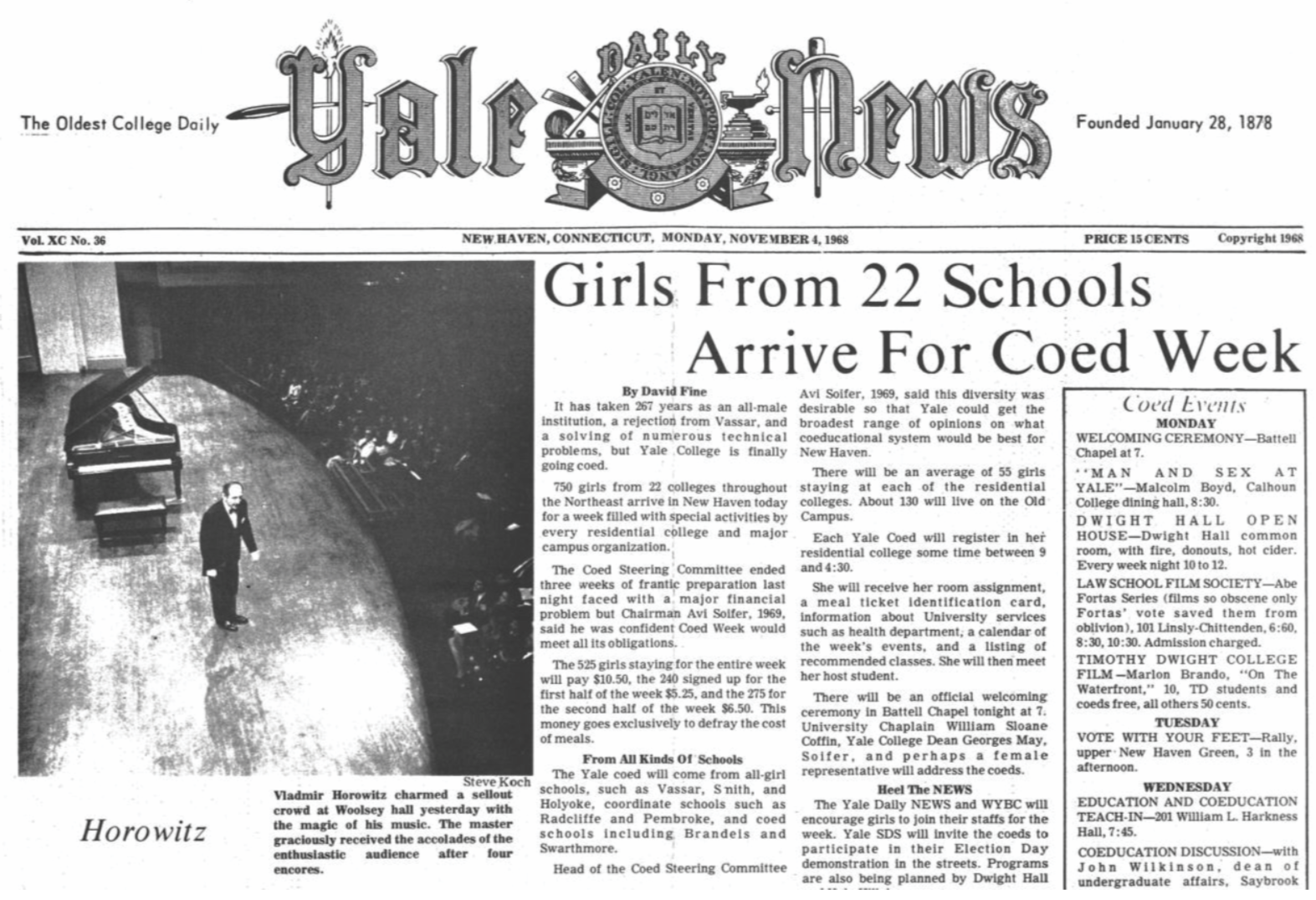

November 4, 1968

Pressure to bring coeducation to Yale College had been building since at least our freshman year. Yale President Kingman Brewster had proposed to resolve the matter by formally affiliating Vassar College with Yale and moving it to New Haven. But in 1967 his plan was rejected by Vassar’s trustees. Coeducation efforts stalled until Yale undergraduates, led by our classmate Avi Soifer, organized “Coed Week,” a brilliant ploy to force the administration to implement undergraduate coeducation by simply admitting a large number of female students to Yale College and housing them in the Old Campus and the residential colleges. This tactic succeeded marvelously.

November 25, 1968

Although Yale had not been considered a national football powerhouse since the early twentieth century, enthusiasm for the 1968 football team swept the campus as it demolished one opponent after another and the Yale Daily News cartoon strip “Bull Tales,” authored by Garry Trudeau, 1970, celebrated the heroic deeds and philosophical ruminations of its players. So stunned disbelief greeted the 29–29 tie of the theretofore seemingly invincible Bulldogs by the Harvard Crimson (who were also undefeated). The dismay of the Eli fans was compounded by the fact that the Crimson scored the final 16 points of the game in a little over 42 seconds.

May 12, 1969

The growing anti–Vietnam War protest movement at Yale generated efforts to strip the ROTC programs of academic credit and remove them from campus, to campaign for elected officials like Allard Lowenstein who opposed the war, to raise money for the appeal of Yale Chaplain William Sloan Coffin’s war-related criminal conviction, and to support resistance to the military draft by students about to graduate or otherwise leave college. So it was not surprising that our class decided, among other measures, to focus our commencement ceremony on opposition to the war by featuring an anti-war speaker and to establish a legal defense fund for those classmates who, if drafted, refused induction.