William Kurt Sacco, February 10, 2024

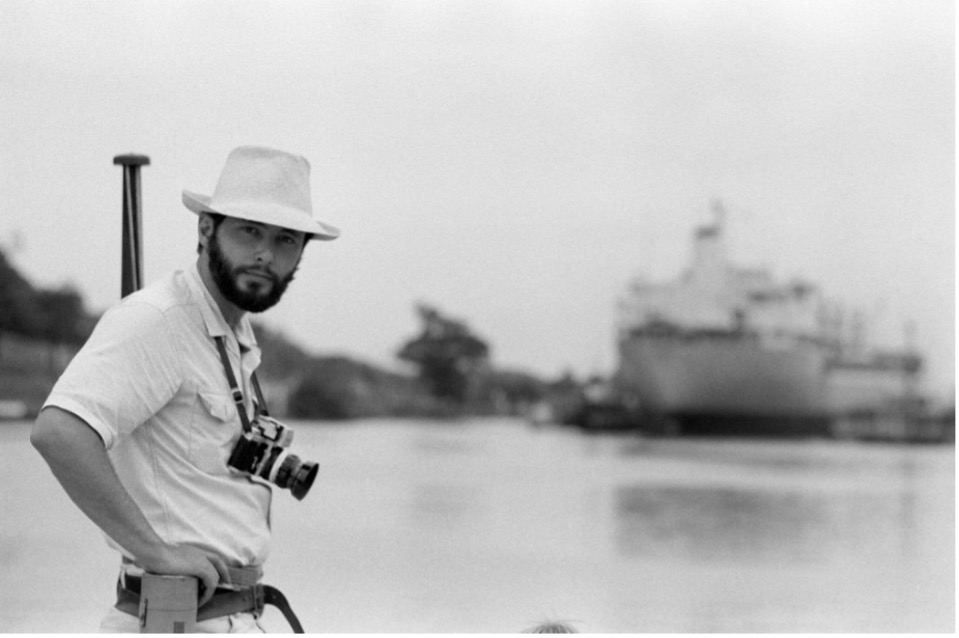

My best friend at Yale, Bill Sacco, passed away on February 10th, 2024. Bill was one of the most talented photographers of our generation.

My best friend at Yale, Bill Sacco, passed away on February 10th, 2024. Bill was one of the most talented photographers of our generation.

Our friendship began in sophomore year on the day we moved into Silliman College. While everyone else was upstairs trying to make their new rooms livable, Bill and I converged downstairs in Silliman’s photographic darkroom. We both looked at the enlarger. “Schneider lenses,” I observed. “Yes, but no Tiffin filters,” Bill commented. Professional colleagues whom you also like! This is one of the gifts that Yale can give.

Both Bill and I were interested in photographing the natural world. Also, we were both science majors, Bill in Geology, I in Biology. Both of us wanted to take photography during our senior year to advance our interest in science, but enrollment in Art Department courses was so limited for non-art majors that neither of us could get in. We hatched a plan. Yale had launched a program that permitted students to create new courses if we could find a notable instructor. Life Magazine already had a Writer-in-Residence program at Yale. What if we changed the first word to Photographer-in-Residence? Somehow it worked. (As an aside, when word got out that our photography course would be taught by Staff Photographers from Life Magazine, art students signed up for our course rather than from the Art Department!)

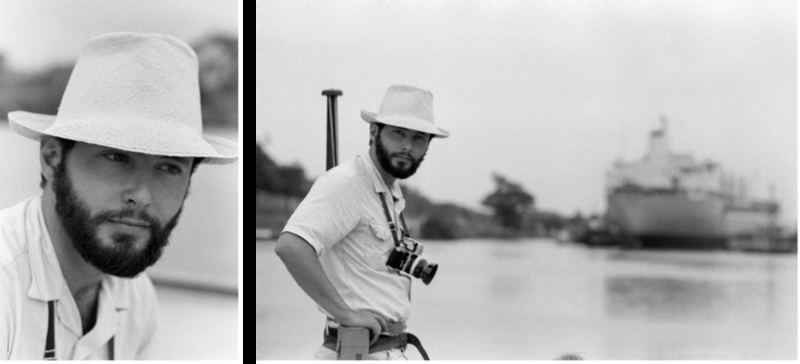

Photographers almost always specialize. They specialize in portrait, landscape, nature, sports photography, etc. Bill, however, did it all. As a scientific photographer for the Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale, he photographed all creatures great and small. While pushing the boundaries of photographic microscopy, he was also considered Yale’s finest portrait photographer. Invariably, Bill was able to put his subject in their best light. His portraits of Yale faculty remain the gold standard of portraiture even today.

Spring semester of our senior year also corresponded with Yale’s Co-Ed Week. Life Magazine deputized Bill and me as “Life Stringers,” replete with Life Magazine Press Cards, press badges, and, most importantly, free film. Life sent their staff writers up from New York to get the story, but relied on the campus ‘stringers’ for all the photographs. I remember the writers wanting to make sure our student photography on the story would support their professional writing. One writer asked Bill, “Are you getting good pictures?” With his ever-present wit and dry humor, Bill shot back, “Are you getting good words?” The next week, Bill’s photos were seen round the world.

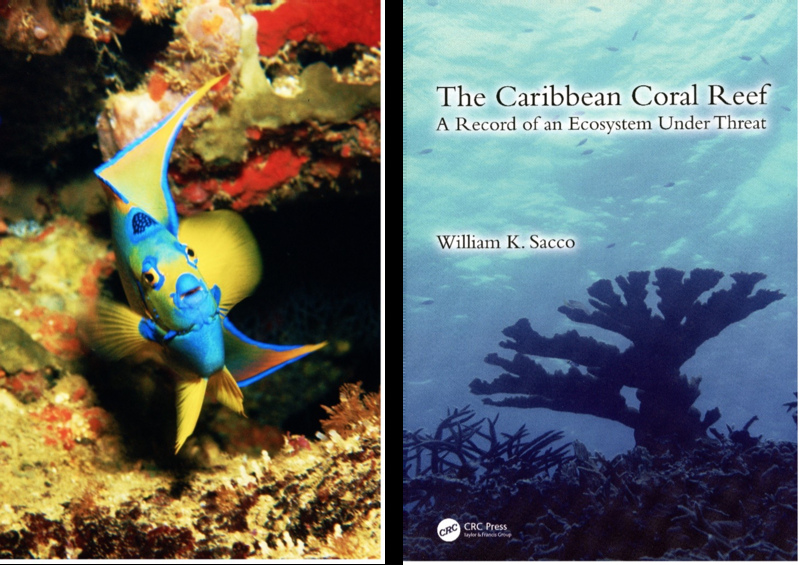

Bill had an exceptional eye for composition. One of his distinguishing hallmarks was his ability to put his subject in lovely context within its surrounding environment. One reviewer said of his Caribbean Coral Reef book, “It should be noted that as that as difficult as fishes are to photograph, Bill’s images are simply amazing – you believe you are there!” Another said, “Bill’s photography connects the viewer’s heart and mind.” And another stated, “By revealing in extraordinary detail and vivid color the stunning beauty of coral reefs, Bill develops a powerful conservation message to preserve and protect these biologically diverse, and yet critically endangered ecosystems.”

Bill was a good cook. And an inventive one too, especially at large gatherings. For a summer-time bash, Bill found a frying pan that all of us swore was at least 3’ in diameter – it was certainly too heavy for one person to lift – and made his own version of an Italian dish ‘Rigatoni Democracia’ (in honor of the Fourth-of-July) which fed more people than the miracle of the loaves and fishes.

Bill was a passionate collector of vintage Griswold frying pans. He celebrated when, at a most inauspicious looking flea market, he found a Griswold #13 for a dollar. The collector’s Holy Grail, for a song!

Bill was a consummate conversationalist. About anything. With anybody. It was as much the way he listened as what he said that made the interactions so engaging and uplifting. It was fun to watch him conversing with such charm.

Bill majored in Geology, but, because he never turned in his senior thesis, he did not graduate. I know he did the research because he and I dived together to collect the samples for his project, “The Effect of Clam Boroughs on Sediment Particle Sizes in Block Island Sound, Connecticut.” Having now spent 50 years in academia, I know from personal experience there are so many, many ways to handle a situation like this — ways that ultimately would have put Bill across the finish line, with his degree from Yale. But for reasons, now lost to time, these solutions were never offered, never implemented.

Bill’s widow reached out to me after his passing, wondering if I knew what could be done with his prized collection of underwater slides from Jamaica. These slides are the original images for his award-winning book The Caribbean Coral Reef, A Record of an Ecosystem Under Threat. I was dumfounded by her request. It is one of those instances where a coincidence pushes up against the boundary of a miracle. I had just given all of my slides of Jamaica to the West Indies Division of the British Museum of Natural History. They were looking for more material. OMG. The Museum’s first Director, Hans Sloane lived in Jamaica from 1687 – 1689. When he moved back to London and founded the British Museum in 1707, he used his Jamaica material to create the Museum’s first public display. Between that and Jamaica’s membership in the British Commonwealth, the Museum cherishes and passionately collects all things Jamaican. The British Museum of Natural History is not just a repository for Bill’s work. It is a temple.

Bill began his photographic career at Yale’s Peabody Museum of Natural History. If you have seen images of the dinosaur mural, you have seen his work. He went on to publish extensively in Life Magazine and the New York Times. Bill finished out his career in Yale’s Media Department as a photographer, doing the work he loved.

Bill is fondly remembered by his wife Jan and their two daughters, Cristina (Judge) and Elisabeth (Klock).