‘A Very Unwelcome Feeling’: The First Women at Yale Look Back

from NYTimes: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/30/upshot/yale-first-women-discrimination.html

by: Claire Cain Miller, 10/30

A new survey and book show that for organizations to diversify, it’s not enough to let new people in. The institutions have to change, too.

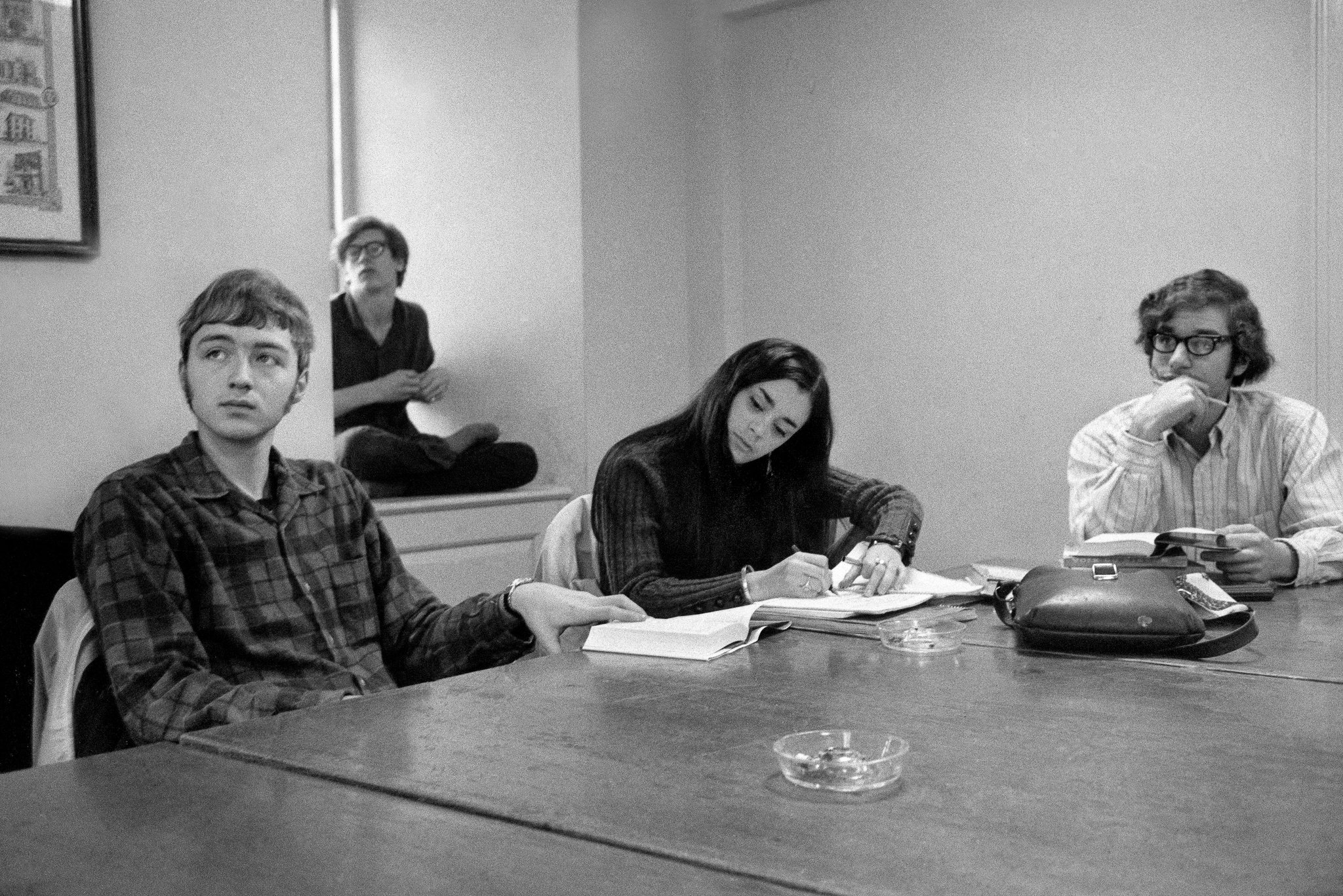

Credit:Carl T. Gossett/The New York Times

When the first undergraduate women to be admitted to Yale arrived on campus 50 years ago this fall, they were outnumbered seven to one. To prepare, Yale installed full-length mirrors in the women’s dorm rooms and, to the dismay of many men, banned nudity in the gym. But there were no women’s studies classes, no women’s competitive sports and little idea how to support women at a place that was, in 1969, the oldest all-male college in the country.

Sixty-five percent of them had a class in which they were the only woman, according to an unpublished survey, conducted this year, of nearly half the 575 female freshmen and transfers who entered in ’69. About half never had a female instructor. Sixteen percent said they were sexually harassed by Yale professors or authorities, and the university had no system for reporting it.

Women weren’t allowed to have lunch at Mory’s, a private dining club where important meetings took place. They were barred from most extracurricular activities. And Yale severely limited the number of women who could be admitted, as described in a book about the class, “Yale Needs Women,” published last month by Anne Gardiner Perkins, a historian.

The experiences of the first women at Yale tell a bigger story about what happens when institutions that have been dominated by white men try to diversify. Yale, like many places of power, allowed women to enter. But it didn’t treat them as equals.

“For places like Yale or Congress or the White House, the battle for equity only begins when you open the door and let women in for the first time,” Ms. Perkins said. “It requires the institution to change.”

By 1969, most public universities and those in the Midwest and West were already coed. Elite, private and Roman Catholic institutions in the Northeast were lagging (but by 1973, most of them were coed, too).

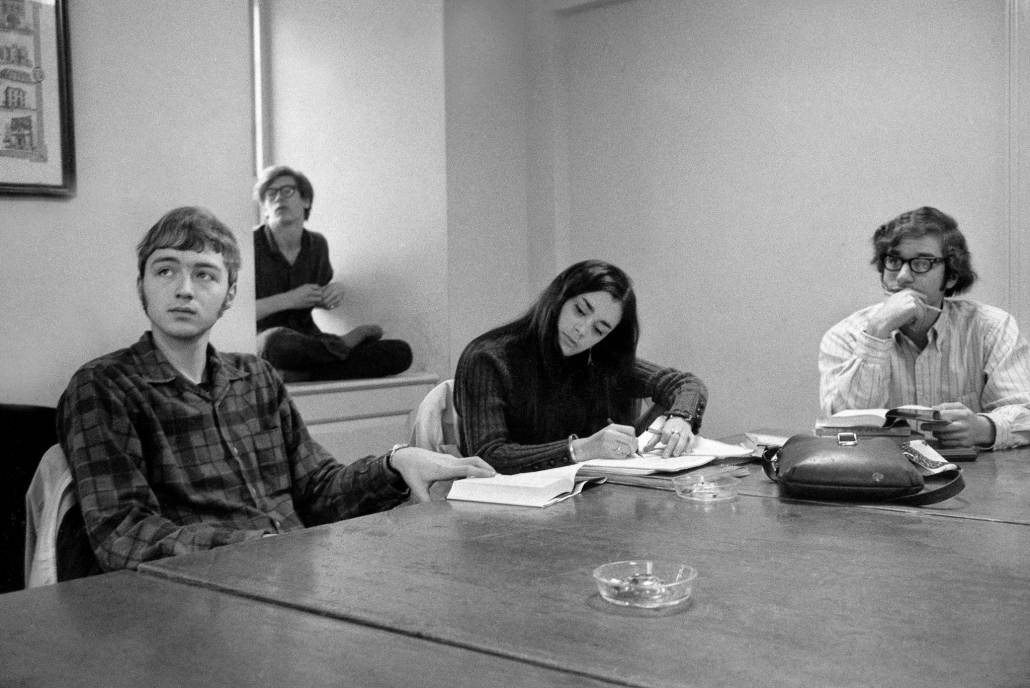

Credit…Patrick A. Burns/The New York Times

Yale set out to educate “1,000 male leaders,” and male applicants needed to demonstrate academic achievement and leadership potential. But women weren’t assumed to be leaders, Ms. Perkins wrote. So in addition to academics, they were evaluated on grit — “a certain toughness, a pioneer quality,” Henry Chauncey Jr., an administrator at the time, told The New York Times in 1969. (The article ran alongside an ad for children’s clothing: “Girls’ styles are colorful and pretty; boys’ styles are fun-loving and rugged.”)

One way to find gritty women, according to Yale? Admit those who were raised with brothers — the more the better. Of the survey respondents, 93 percent had at least one brother.

Besides being sexist, the different admissions criteria were an acknowledgment that assimilating at Yale would largely be the responsibility of the individual women.

Other places of power that have diversified in the last half century have presented similar challenges, including Congress, said Representative Sheila Jackson Lee, a Texas Democrat and a member of Yale’s first coed class. At both institutions, she said, it was common to enter a room and see no other women, let alone another African-American woman like her. But she became a campus leader, in the civil rights movement and as a church deacon.

“They were leaders in a man’s world,” she said of the first women, “and, yes, they had grit, and because they had grit, their leadership was not going to be snuffed out.”

“That doesn’t mean it wasn’t challenging,” she added, “because they weren’t entirely prepared for us.”

Sally Birdsall, who runs a land-use planning firm in Greenwich, N.J., studied architecture as a member of the first female class. She remembers that a professor told her she would be unable to do a building project because she had never played with an Erector Set (she had). Another warned the women attending his lecture that he did not want to hear knitting needles.

“I was upset, not because I had a knitting needle, but I was more scared,” she said. “It just gave you a very unwelcome feeling.”

The administration had done little to incorporate women. It appointed Elga Wasserman to oversee coeducation, but she had the budget for only a secretary and an intern, Ms. Perkins said. There were no formal meet-ups for women, who were divided among 12 dorms. Female graduate students acted as advisers, but there were no trained counselors. There were three tenured female professors that year.

The students were at the forefront of the women’s movement of the 1970s, which demanded that women be full participants in society. Many were also involved in other causes, including abortion rights, the Black Power movement and Vietnam War protests.

“In the late 1960s, as the women’s movement takes off, there are these super smart women who have been mobilized — not all wealthy, not all white — and they’re frustrated by the way the intellectual world is telling them what they’re thinking or saying is not important and shutting their doors on them,” said Kirsten Swinth, a historian at Fordham and author of “Feminism’s Forgotten Fight,” a history of the period.

Ninety percent of the survey respondents said they were Democrats. Entering an all-male institution probably shaped those views, several said.

Their experiences illustrate how much has changed in 50 years — and how much has not. The birth control pill was illegal for unmarried women in many states, including Connecticut (so was abortion). Yet 83 percent said they took it, according to the survey, which was privately presented at a reunion this fall of the first women and provided by an attendee. Most got a prescription from Yale’s new gynecologist, who had an agreement with the police to look the other way, Ms. Perkins wrote.

In their post-college achievements, they were unusual among American women their age, and faced challenges that have become familiar to highly educated women today: how to achieve educational, career and family goals when they’re all running on the same clock.

Eighty-nine percent received advanced degrees. A third became the primary household breadwinners, and a third described themselves as homemakers. Fifty-nine percent said they faced gender discrimination that stunted their careers.

Eighty-two percent of respondents had children, and their average age of first birth was 33. The national average at the time was 21. (Today it is 26, and 30 for those with a college degree.) More than a third said they delayed having children for career reasons, and nearly a third said they struggled with infertility.

Sixty percent said both they and their partner worked full time. But half that share said their partners shared in responsibilities like housework and cleaning.

“I certainly felt that with opportunity came obligation, and I needed to use my degree,” said Catherine J. Ross, a member of the first class, who also received a law degree and doctorate from Yale and is now a law professor at George Washington.

“We talk a lot about how shocked we are,” she said. “We never imagined that 50 years later, women would still be struggling to be treated fairly in the workplace, to be compensated fairly and to balance work, love and family.”

Another facet of this soldier-on attitude, for many women, was keeping quiet about the sexual transgressions they endured. In 1969, “sexual harassment” was not yet a legal term, and discrimination against women at universities was not outlawed. One in six survey respondents said they were harassed by faculty or staff. The survey did not ask about assaults by fellow students, but anecdotes suggest it was not uncommon.

“I think most of us buried it at the time,” Ms. Ross said. “It wasn’t something people talked about in public. For me it was, I really wanted this to work.”

Yale women would end up playing a crucial role in making sexual discrimination on campuses illegal and putting in place grievance procedures for harassment nationwide, including in two groundbreaking Title IX complaints, Alexander vs. Yale in 1980 and another in 2011. Yet new research finds that sexual assault on college campuses continues to be prevalent and underreported.

Alexandra Brodsky, one of those who filed the 2011 complaint, said things had improved since she graduated in 2012. “I think that Yale now has staff and programming to address issues of gender equality that they did not have when I entered,” said Ms. Brodsky, a civil rights attorney. “There’s a common vocabulary that students now have to talk about a culture of violence, a culture of misogyny.”

“I guess that’s how history and change work,” she said. “Coeducation is so recent. In the history of Yale, women are a blip.”