Black at Yale 50 years ago

As I think back fifty years since our graduation from Yale, I’m fortunate to have one significant artifact to help jog my memory. That artifact is a thin, worn, paperback volume on my bookshelf entitled Black Studies in the University: A Symposium edited by my fellow students, Armstead L. Robinson, Craig C. Foster, and Donald H. Ogilvie, published fifty years ago by the Yale University Press. Sadly, Armstead and Don of the Yale Class of 1968 have passed away, but Craig, our classmate, is with us and has lent his editorial eye to this essay. Thank you, Craig!

As I think back fifty years since our graduation from Yale, I’m fortunate to have one significant artifact to help jog my memory. That artifact is a thin, worn, paperback volume on my bookshelf entitled Black Studies in the University: A Symposium edited by my fellow students, Armstead L. Robinson, Craig C. Foster, and Donald H. Ogilvie, published fifty years ago by the Yale University Press. Sadly, Armstead and Don of the Yale Class of 1968 have passed away, but Craig, our classmate, is with us and has lent his editorial eye to this essay. Thank you, Craig!

I’m guessing not many of our classmates are aware of this book, much less the coincidence between the year of its publication and our graduation. Nor would I guess many of our classmates are aware of the coincidence between the year of our graduation and the founding of Yale’s undergraduate major in Afro-American Studies. Nor, finally that the Black Student Alliance at Yale (BSAY) celebrated its fiftieth anniversary in October, 2017. I mention this lack of familiarity not as an indictment, but as an acknowledgement that the Yale experience is fascinatingly diverse.

But first the familiar: moving-in day(s?) on the Old Campus our freshman year: meeting our roommates, their parents, relatives, furniture, phonographs, wall posters, etc. At that time, a whirlwind of the unfamiliar, actually. And at some point during that week, along came the aforementioned Armstead Robinson and Donald Ogilvie, dashiki-clad (at least in my memory), welcoming me to Yale and to Morse College. And to an emerging coalescence that would eventually be known as the Black Student Alliance at Yale.

An African American student entering a majority-white university doesn’t arrive without some curiosity about the relative representation of “one’s people.” At least not those African Americans who are accustomed to thinking in terms of “one’s people.” Black and white photographs in the Yale College Bulletin are notoriously unreliable. Armstead and Don were eager to share the racial demographics of Yale’s student body with the African American freshmen they welcomed. By our collective count, our freshman class included twenty-four African American students, two per residential college. Coincidence? Symmetry, at least. Nevertheless, that two dozen of one thousand freshmen nearly doubled the number of African American students in the class of 1968, which was nearly double the number in the class of 1967. Despite our small numbers, the percentage of African American students in several successive classes was clearly increasing.

The public discourse on this trend was debated mostly in terms of social class, not race. Kingman Brewster, President of Yale University at that time, and his newly appointed Director of Admissions, R. Inslee Clark Jr. (1965) had agreed to expand the talent pool from which Yale recruited its student body by enacting a needs-blind policy for all applicants. As a result, the percentage of undergraduates who entered Yale from private schools dropped nearly 10 percent, from roughly 50 to 40 percent, and the percent of alumni sons decreased by nearly half, from 24 to 13 percent. These social class shifts in the composition of the Yale student body received more attention from angry alumni than the arithmetic doubling of the relatively small total of black students. Still, Yale was achieving larger numbers of African American students on campus years before “Affirmative Action” became a convenient target for those who opposed this trend.

The increasing number of black students at Yale certainly got the attention of those of us who’d arrived. One item on the agenda of black students who had begun to organize on campus was the need to increase the number of qualified black applicants who applied to Yale. To that end, a cadre of black students approached the Yale admissions office with a proposal that current students go out and recruit potential applicants in their hometowns during our college vacations. I wish I could report the deliberations that occurred among Yale admissions officers at that time, but what I can report is that those of us who volunteered for this service received promotional materials that we proceeded to distribute at presentations we organized at high schools in and around our home neighborhoods. Although we couldn’t prove a causative connection, the number of black admissions to the class of 1970 doubled yet again.

One unanticipated outcome of the increase in the number of black students at Yale—unanticipated among administrators, at least—was the desire among some black students to live in close proximity to one another. As most college graduates will likely agree, a substantial contribution to one’s education—at least for students in residential colleges—is the dialog (i.e., bull sessions) among classmates in dorm rooms. It had been Yale’s practice at that time to allow prospective sophomores to submit the names of classmates they’d like to live next to after their freshman year on Old Campus. When the administrators at Morse College realized that Armstead, Don, Craig, and I wanted single rooms near each other, they decided it was time for a meeting.

That meeting proved to be a wake-up call for me. Whereas I’d assumed Yale had admitted me for my academic talents (I was a mediocre baseball player at best!), I heard an administrator declare that one reason black students were admitted was to integrate ourselves with non-black students, and our proposal to live within close proximity to each other would undermine that goal. That was a shocker. Our counter-argument was that we typically found ourselves the only black student in our classes and that, as a natural outcome of Yale’s racial demographics, we were more often than not helping Yale accomplish its goal. For us, time together would be the exception to the rule. As it turned out, our argument prevailed, and we spent the next three years making sense of our Yale experiences in each other’s rooms. On the other hand, we’d glimpsed an institutional goal that had little to do with our growth as students.

Like most undergraduates, a good deal of our “making sense” of Yale involved talking about majors, courses, girlfriends, grades, weekends. The Game. The War. More on the latter, later. At this point in this essay, two topics need to be mentioned as particular to our discussions of the black experience at Yale. The first is our debates over who among us could claim to have lived an “authentic” black life. I prefer to believe (on hindsight) that these “essentialist” discussions were short-lived, but I have to acknowledge they took place and that, given our different backgrounds, we came to understand the multiplicity of the black experience.

The second topic of discussion was more profound and enduring. Where was representation of the black experience in any of our courses? As a psychology major, I was troubled by the discovery that the study of human behavior was founded primarily on the study of white male college students. Our assigned readings were similarly limited. Armstead, Craig, and Don noted comparable shortcomings in their studies of history and political science. Further, we were aware that simply adding texts or even courses that addressed the black experience would not be a sufficient response to our complaint. In the field of psychology, for example, texts such as The Mark of Oppression and Dark Ghetto portrayed the black experience as psychologically damaged. We understood our experiences very differently than these authors. For us, a curriculum that incorporated the black experience would require more than simply adding “black content.” Interpretive frameworks and perspective-taking would have to be an integral part of this new curriculum.

Our conversations extended beyond our dorms, of course. Questions about Yale’s curriculum were a continuing item on the agenda of a broader group of black students that had been coalescing since the fall of 1964: the Yale Discussion Group on Negro Affairs. In 1967, this group renamed itself the Black Student Alliance at Yale (BSAY). This group’s ongoing discussion of the shortcomings of Yale’s curriculum reached its peak in the spring of 1968 with the convening of a two-day symposium entitled “Black Studies in the University.”

I return now to that volume on my bookshelf. That book and the symposium on which it was based were generated in a context of increasing social unrest nationwide. After all, we attended Yale in the latter half of ‘60s, the decade of… you fill in the blank: ________. “Protest?” “Change?” “Promise and Heartbreak?”. With regard to race relations, it was a decade of civil disturbances or, colloquially, the decade of “race riots.” The violence that erupted in Detroit, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Newark in the mid-sixties prompted President Lyndon Johnson to appoint a commission in 1967 to discover the cause and remedy for this social unrest. That commission issued its “Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders” in February 1968, only months before the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. gave rise to further incidents of civil disorder in a dozen additional cities. College campuses were also sites of protests and demonstrations in 1968 as black students at Northwestern and Columbia disrupted the status quo at their universities.

Such was the racial climate in the country when the Black Student Alliance at Yale petitioned the university to host a symposium among invited scholars, black and white, to consider whether establishing a series of courses focused on the study of the black experience from a variety of disciplinary perspectives was “academically responsible and intellectually defensible.” That symposium, involving about 100 predominantly white representatives from some 35 colleges, universities, and K-12 public school districts, was held on campus on May 9 and 10, 1968, without any disturbances or disorder due to pains taken by the Black Student Alliance to provide an atmosphere that was free and open for these deliberations. By the end of the symposium, Yale faculty and administrators voted to approve a Black Studies program that would allow students to major in a traditional discipline and supplement their coursework with courses that focused on the African American experience. While the program continues to evolve, this symposium and its student and university leaders created a turning point in higher education as they took to heart the critique voiced by Armstead Robinson in its concluding statement:

“American educators must face the reality that their educational system has failed in the most fundamental ways to provide learning experiences that are relevant to blacks. They must realize that the root cause of this failure is racism, the type of racism, conscious or unconscious, which dictates not only the choice of materials to be presented…. Black studies or Afro-American studies, must be included in the general curriculum.” (“Black Studies in the University,” pp. 207-208).

These were exciting days indeed and I realized we were not only making sense to each other, but also making sense to Yale faculty and administrators and, in the process, making history. Still, on a Yale-sponsored flight to the University of Wisconsin-Madison to recruit Professor Roy Bryce LaPorte to become the first director of Yale’s new department of African American studies, it also struck me that we were still students—missing classes, postponing assignments, and, hopefully, passing our courses! Concern regarding the latter caused me to withdraw from my classmates’ commitment to publishing “Black Studies in the University”—the road not taken, I think back on it now. But my awe at their commitment and their accomplishment lingers to this day.

Another lasting legacy of 1969 was the establishment of the Afro-American Cultural Center at Yale University in the fall of that year, a few months after our graduation. Of course, it took a great deal of discussion to convince the school’s administration that a Yale-sponsored race-specific space was not only defensible with regard to the well-being of the school’s growing black student population, but could also add value to the Yale community at large, including the city of New Haven and Yale African American alumni. Although I cannot recall the details of those conversations, I can report that I became the first manager of what affectionately became known as “The House”—and later, The Afro-American Cultural Center—in the fall of 1969.

The House, initially located at 1195 Chapel Street, served as a meeting place for the Black Student Alliance and the home of the newly established Urban Improvement Corps, a work-study program that employed Yale African American undergraduates to tutor students from Troup Middle School. Alan Woods (‘68) served as the first coordinator of that program. I served as the second coordinator. In 1970, the House moved to its current location on campus, 211 Park Street and Raymond Nunn, ‘69, provided leadership as coordinator.

Currently, The Afro-American Cultural Center houses forty resident groups—at last count! Frankly, I’m amazed. I last visited the House in early October 2017, on the occasion of the fiftieth Anniversary of the Black Student Alliance at Yale, and I was struck by the diversity of the students’ academic, social, and political interests. Forty groups! Yet capable of coalescing to celebrate our collective history on campus. That diversity and cohesion is a testament to the growth that has occurred since the late ‘60s. I have no doubt, however, that representatives of the House must continue to advocate for its relevance among the competing interests that vie for the university’s resources. Yet I also have no doubt that they do so from a position of strength.

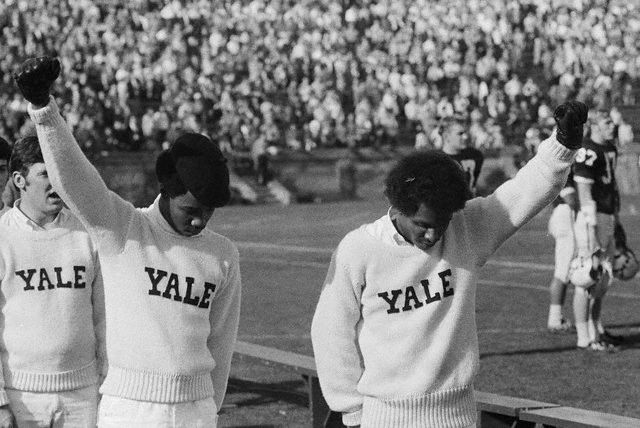

Returning to the 60s, I should note that a competing concern among black students at this time was the war in Vietnam. The Black Panther Party became more active and visible in New Haven toward the end of the decade as did the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). Alliances of these groups and individual students culminated in a campus-wide strike in the spring of 1970. Although the strike occurred after our graduation, it was virtually impossible for black students not to consider involvement in the antiwar movement for many reasons, including the disproportionate number of casualties suffered by black soldiers engaged in this war. The Black Panther party was especially assertive in trying to recruit black Yale students to join its anti-poverty, anti-racism, anti-war mission. I recall whispering to Craig (Foster) during one of those meetings: “My parents will kill me if I drop out of Yale to join the Panthers.”

Thinking back on it, my ambivalence about joining the antiwar movement stemmed from a variety of factors. There was my coursework, of course. And my involvement in the Black Student Alliance. Also, a sense of social distance from the predominantly white leaders of the antiwar movement. Perhaps a lesser understood reason for ambivalence was that antiwar protesters calling for greater disarmament hadn’t addressed the consequences of their call on the large number of black workers employed in Connecticut’s armament industry: Colt Manufacturing in Hartford, Winchester Repeating Arms Company in New Haven, and Remington Munitions in Bridgeport. This issue was especially poignant for me given that I’d taken a job as a cafeteria busboy—as a freshman scholarship recipient—a job that might have otherwise gone to a New Haven resident. These were the thorny issues I recall grappling with during those days of “Protest,” “Change,” and “Promise and Heartbreak.”

Of course, in addition to engaging these serious social-political issues, we also made time for partying. In 1964, black students at Yale invented an annual ritual that became known as “Spook Weekend.” (Spook: “a derogatory slur for a person of African descent”, Urban Dictionary). In this case, however, said persons of African descent transformed the term “spook” to signify hundreds of black undergraduates from the Northeast who gathered on the Yale campus for a joyous weekend of serious partying. For me, it was a welcome alternative—even if it occurred only once a year!—to the college “mixers” and the weekend road trips I couldn’t afford. Yet, as I try to recall the actual settings, music, the trysts, etc., I’m reminded that it was almost sixty years ago, a lifetime for so many.

Which brings me to my final remarks: in memoriam.

In the May/June 2011, issue of the Yale Alumni Magazine, in an article entitled “Before Their Time,” Ron Howell (African American, ‘70) wrote: “…I did some counting and came up with 84 members of the Class of ‘70 who were deceased, nine of them blacks who entered with us (class of ‘70) in 1966. Thus, while we African Americans were 3 percent of the class of 1970, we were more than 10 percent of the deaths.” He goes on to note that his sampling was not scientific but he is conveying a pattern many surviving African American Yale graduates have recognized.

While it’s difficult to identify specific causes for this disparate mortality, a general consensus among physician/researchers—notably African Americans—is that excessive stress is likely a contributing factor. In his article, Ron quotes our classmate Craig Foster who wonders “…whether some of the brothers see death as the honorable way out…In dying of stress, you leave open the perception that you fought the good fight, that you took your sword and resisted the onslaught of your enemy before you finally went down yourself.” Along these lines, several black physicians refer metaphorically to “John Henryism” to explain this disparity. As legend has it, John Henry, an African American folk hero, died in a race with a steam-powered drill hammering spikes into rock to make holes for explosives in constructing railroad tunnels. He won the race against the machine only to succumb from the stress of the effort.

Demographers have long noted racial inequalities in life expectancy for black men and women, ironically increasing with increases in social status. Unfortunately, identifying the pattern is easier than identifying its cause. Explained or not, that pattern has cast a long shadow over the lives of those of us who’ve survived. What we can do in the time we have left is keep the memory of our brothers’ efforts alive and dedicate to them our own remaining efforts.

That is what I’ve tried to do in this essay. I realize much has been omitted—individuals’ names, particular places, precise dates, important events, specific groups and, especially, the spirit and camaraderie with which we undertook our challenges during our time at Yale. Nostalgia is a complicated emotion and while I feel pride in what we accomplished, I lament not having my comrades by my side to celebrate with me. Still, I appreciate the opportunity to share memories of contributions of which I guessed many of my Yale classmates had been unaware. Thereby reducing the gap. After fifty years.

Your retrospective of the challenges and risks you guys and the administration overcame to improve the college speaks volumes to the Yale experience. Thanks, Roger.

Those are awesome insights and observations, Roger — and extremely well articulated! Thanks for sharing your experience. Your efforts, I would argue, were successful in making Yale more accessible — and more relevant— to a much broader and more diverse group of students.