That Was The Week

In the fall of ’68, as five determined linemen were protecting Brian Dowling out at the Bowl, “1,000 male leaders” were protecting Woodbridge Hall against the onrush of undergraduate coeducation.

That thousand was us. Kingman Brewster’s mandate from the Yale Corporation was to protect those dedicated places for men, which women should not displace when they arrived. Hence, new housing should come first. Brewster favored coeducation, of course, and it was never clear whether he was squirming under Corporation strictures, or whether he was secretly glad for the excuse to move with only deliberate speed.

One Normal, Non-Sensational Week

Coed Week was our own class’s unique, life-changing contribution

But then, in one “normal, non-sensational Yale week,” the stalemate vaporized. The success of Coed Week led, within days, to Yale inviting women to apply for 500 undergraduate places in the very next admissions cycle. We might regret, as our yearbook did, “the truism that history confers its benefits on the latecomer,” but Coed Week was our own class’s unique, timely, life-changing contribution to a great institution. Whether or not as individuals we played any part in it at the time, at this distance it is something all of us can be proud of.

Best of all, and a key factor in its success, Coed Week was a kind of strategic judo that was quintessentially Yale, using the institution’s own prized values against it. You say, Mr. Brewster, that housing is a main obstacle? The dorms and dining halls just handled nearly 1,000 extra bodies, all female. Administrative logistics? Students handled it. Rational, practical reasons not to proceed, rationally disproven with actual practice.

And style? You, Mr. Brewster, are civility and willingness to engage in open-minded discussion, incarnate. Coed Week played back the same style, during a time when student marches and maybe torches could have been imagined. The result — “gentlemanly student activism” in the New York Times’s version – was irrefutable in manner as well as method. It spoke their own language, almost perfectly, to the crucial few sets of ears that mattered most.

So how did it come about? From the perspective of fifty years on, the details are still delicious. And (interactive spoiler alert) there are sound recordings of perhaps the exact moment of dénouement, that you can hear on this website — just scroll down. But first, some background.

Starting in 1962

Undergraduate coeducation in some form had actually been on the Yale agenda since at least 1962, when the faculty had deemed it “a national duty.” With JFK as President, the Admissions Office also felt it was losing more and more of its best applicants to Harvard, due to the allure of Radcliffe, plus Kennedy glamor.

In 1963, at age 44, Kingman Brewster Jr. became President. He promptly caused alumni heartburn by urging higher academic standards and greater diversity in the student body, using his perfect Yankee and Yale credentials to push for more public school graduates, non-East Coasters, and other categories of under-represented achievers, with Inky Clark, his new 30-year-old admissions director, making it happen.

(Old Blues were furious that their equally Eastern, equally WASP sons weren’t getting in any more, and William F. Buckley, Jr. ran hard for a seat on the Yale Corporation to turn the tide; but he was beaten by Cyrus Vance père, maintaining Brewster’s support.)

Money was also much on the new President’s mind, and not just for new women’s dorm rooms. Coeducation seemed to cut both ways. He foresaw long-term decline in academic quality, and thus funding decline, if Yale College stayed single-sex, but alumni anger at coeducation was threatening to choke off some of the donations pipeline right away.

The Vassar Dance

In 1966, the Yale Corporation officially instructed Brewster to explore coeducation options, as long as the 1,000-male minimum was maintained. With a Radcliffe “coordinate college” model in mind, he quickly began a courtship with Vassar, in whose President, British historian Alan Simpson, he found a kindred spirit (and both men’s wives were Vassar graduates).

In 1966, the Yale Corporation officially instructed Brewster to explore coeducation options, as long as the 1,000-male minimum was maintained. With a Radcliffe “coordinate college” model in mind, he quickly began a courtship with Vassar, in whose President, British historian Alan Simpson, he found a kindred spirit (and both men’s wives were Vassar graduates).

Talks about a Vassar move to New Haven went well, and in 1967 that looked like the plan, but opposition from Vassar trustees, alumnae, and faculty killed it by the end of the year, leaving Brewster touting a “Vassar-type” coordinate college to be built on the grounds of the Divinity School on Prospect Ave. A Yale Daily News reporter who’d come from a public high school was assigned to cover a Brewster press conference about Yale’s coeducation plans, and his already coeducated ears were surprised to hear talk about “recognizing the unique needs of women in education,” and even a hint of home economics in the curriculum.

1968

Then it was 1968, with Vietnam looming and news of student protests around the world. In March, LBJ announced he would not run again. In April, Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated. Robert Kennedy was assassinated in June. Prague Spring was crushed by Soviet tanks in August. Only weeks later, Richard Daley’s police clubbed journalists and demonstrators in Chicago outside the main hotel for the Democratic National Convention in the presence of that same student reporter, who was then working as a summer intern for the Chicago Sun-Times.

$30 million price tag

As we came back for classes in the fall, Ray Nunn’s Student Advisory Board continued to press for coeducation as Derek Shearer’s had the year before, and Yale’s wing of SDS, emerging gently in comparison with Berkeley’s, Michigan’s, or Columbia’s, challenged the 1,000-male mandate by calling for the next freshman class to be half women (“Women Now, Talk Later”). At the end of September, a Brewster white paper made clear his support for coeducation, laid out three options including the “Radcliffe-type coordinate,” emphasized a $30 million price tag, and hinted that a donor’s preference among the options would be a deciding factor.

The Idea and the Groundwork

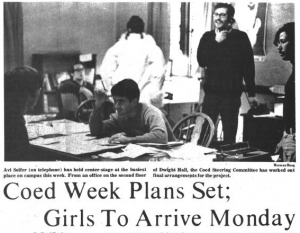

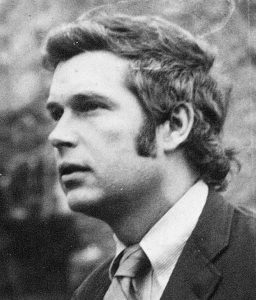

Avi Soifer remembers no light-bulb moment about the idea of Coed Week, but the times felt troubling. “After what I saw in Chicago for the Sun-Times, and those tanks in Czechoslovakia, it felt like you couldn’t rely on the regular system.” He and a few Trumbull friends wanted to see “what coeducation would actually be like,” and show that it could be better than any of the administration’s latest proposals.

On October 16 Soifer called for an ad hoc committee, got an organizing center in Dwight Hall, and almost overnight put out a rough plan, pinned to the first week in November to avoid most mid-terms for the anticipated visitors. He already had solid contacts at numerous women’s colleges, thanks to a short-lived regional college magazine he’d pioneered with Eric Stiffler (BR) that spring at the Daily News as a monthly supplement inserted in over 20 other college newspapers; and his Trumbull compatriot Jim Ward (TC) energetically led canvassing for volunteers to give up their rooms and entryways for the arriving women. (“It was an easy sell.”)

“a shoddily-conducted coed frolic”

On October 22 the News editorialized that “a hastily-organized, shoddily-conducted coed frolic could do irremediable damage to the administration effort to woo [coeducation] donors,” but Soifer’s next-day rebuttal calmly reiterated the plan, revealed support from the administration and Council of Masters (he’d had meetings), and soberly promised “a week-long, responsible consideration by the Yale community of the views of women from a variety of women’s education facilities about women’s education.” The insider homework had been done, in a single week.

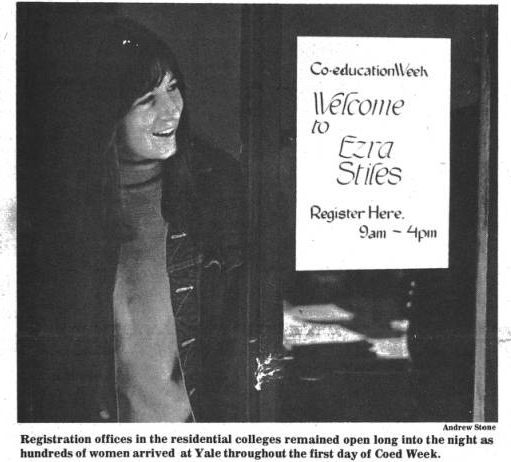

The Event

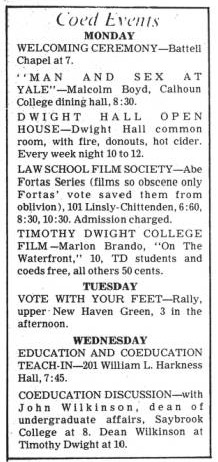

Coed Week happened from the first Monday through Friday in November, with cheerful notes like President Brewster being serenaded at his Hillhouse home by the Yale Band amidst a coed crowd (and merrily yelling back through a megaphone, “Vassar was good enough for me!”), and a mock ad in the News inviting all temporary coeds to an open house at Skull and Bones (“Tell them Avi sent you”).

But it was otherwise the “normal, non-sensational week” that Soifer & Co. had promised, with nothing, at least publicly, untoward. A News columnist dubbed it “astonishingly free of mishap.”

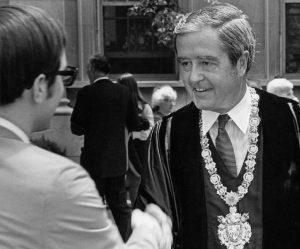

The end-of-week feedback to Brewster from the college masters was highly positive, and Brewster’s message to the faculty the following Tuesday praised the “great competence and responsibility” the organizers had shown, despite moving faster than the administration had wanted. “No word has been heard in criticism, ridicule or scorn of the experiences of ‘coeducation week.’”

The end-of-week feedback to Brewster from the college masters was highly positive, and Brewster’s message to the faculty the following Tuesday praised the “great competence and responsibility” the organizers had shown, despite moving faster than the administration had wanted. “No word has been heard in criticism, ridicule or scorn of the experiences of ‘coeducation week.’”

With unanimous Yale Corporation support, Brewster proposed admitting 500 women in 1969, half freshmen and half transfers, and got a near-unanimous faculty vote.

Before Coed Week, he’d also invited Soifer to a private one-on-one in his Hillhouse study to preview the likely plan, and all three participants (cautious Soifer had brought Jim Ward as a witness) had come away from the parley feeling highly optimistic.

With full Corporation and faculty support for the 500-women-right-away plan, which he’d secured at warp speed, Brewster set up a same-day meeting to announce it to students, choosing Trumbull because it had been the Coed Week epicenter. He could reasonably have expected an ecstatic reception, the whole great ship of Yale turning suddenly and sharply thanks to student action. But part of the housing plan, which had not been part of the private preview, was to scatter Trumbull’s residents to other colleges the next year so that Trumbull could be converted into the residence for freshman women. That did not go down well.

The Dénouement

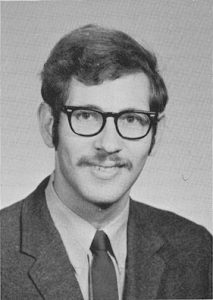

Imagine the Trumbull dining room with chairs stacked on tables to jam in as many electrified students as possible, Brewster alone in the lion’s den. First he talks for 20 minutes, then Soifer responds for seven. You can hear both speeches for yourself, courtesy of Steve Bemis, who taped them. Both men were introduced by Lou Heifetz (TC ’69):

How does it sound to you? To my ears, it’s a near-Platonic ideal of the age-old faceoff between Youth and Experience, which now, in our eighth decade, we can appreciate from both sides.

a near-Platonic ideal of the age-old

face-off between Youth and Experience

Carefully prepared Kingman Brewster, 49, exemplar of progressive and sympathetic authority, lucidly explaining the institutional cross-currents he’d been navigating including that off-stage donor, and doing his best to deliver the bitter pill at the end as sweetly as possible.

Extempore Avi Soifer, 20, hero of Coed Week, passionately but precisely rebutting Brewster’s four-point rationale for where the new women would have to be housed.

But see how you react, to the tones and gists as well as the words.

What then? Four days later the housing plan was redone, putting the freshman women together on the Old Campus instead of in Trumbull, and distributing upperclass women transfers among the colleges instead of off-campus — a last course correction for the ship already irretrievably launched.

The Outcomes. So a small-scale organizational miracle sparked a larger-scale organizational miracle, with the institution moving faster than most insiders thought possible, admitting and accommodating 500 women in fall 1969. Yale solved the housing problem by overcrowding, a temporary solution that lasted a mere 48 years. (The two new residential colleges, faux versions of James Gamble Rogers’ original faux Gothic, finally opened in 2017).

the mysterious donor

$30 million from the mysterious donor went instead to an impeccably Old Blue edifice on Chapel Street, the Yale Center for British Art, housing Paul Mellon’s grand collection in grand, wood-paneled men’s club décor (perhaps to the dismay of punsters everywhere, who lost the chance for a women’s residence on campus named Mellon College).

Today, promotional flyers from the Undergraduate Admissions office proudly tout Yale College’s 57% of students from public schools, its 39% identifying as minority, its 10% international students, and its representation from all 50 states, without bothering to include the percentage of women. Too unexceptional to mention, it’s 49.2%.

and for extra credit . . .

The recording of Soifer’s rebuttal cuts off just before he finished speaking, and he remembers his last sentence as, “Or is it, Mr. Brewster, that you are you afraid of too much fucking going on?”

“too much fucking?”

Not for that moment, which would have been too fraught, but what line would you think up for Brewster to have replied with (perhaps that he might have delivered ten or more years later, when he was Ambassador to the Court of St. James and bumped into visiting professor Soifer on a path at Oxford)?

We’ll post the best ones below as they come in, like a New Yorker cartoon contest.

Brewster back to Soifer:

“Never enough with you, Avi” – Sample

“Vassar wasn’t good enough for you?” – Sample

“Will there be enough to go around?” – Hubert Stiles

“______________________”

“______________________”

Your suggested riposte — witty, poignant, wise, weary, or other:

Special thanks to Anne Perkins, Yale Class of 1981, who’s finishing a Ph.D. dissertation on Yale’s adjustment to women undergraduates from 1969 to 1973; Cyd Cipolla, Class of 2004, who did a paper on Coed Week as an undergraduate and dug through unorganized boxes labeled “Coed Week” that Kingman Brewster had kept, which she found in the Yale Archives; Nancy Malkiel of Princeton, whose 2016 book Keep the Damned Women Out traces the history of coeducation in the Ivies and at Oxford and Cambridge; whoever got the Yale Daily News archive online; Steve Bemis of our class, who made, re-discovered, and donated the Trumbull recordings; the staff of Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library; and of course Dean Avi Soifer of the University of Hawaii School of Law.