It isn’t just the Taliban that’s ousting Americans from Asia

(Op-Ed in Asia Sentinel.)

The End of the Yale-NUS Partnership

A compact built on evangelical arrogance and materialist blundering

By: Jim Sleeper

Yale College’s much-celebrated venture into the wealthy island city-state of Singapore seemed a harmonious convergence, the host country paying all the bills of the Yale-National University of Singapore’s bills and Yale’s visibility and allure ascending among Southeast Asia’s burgeoning middle-class families.

Yet Singapore’s dismissal of Yale, announced late last month, illuminates a lot of what has driven the Taliban’s far-more brutal expulsion of America from Afghanistan: Americans’ own addiction to a drug cocktail of evangelical arrogance and materialist, militarist blundering.

Willful innocence of other countries and cultures has driven many American military and pedagogical misadventures abroad, and it has generated bitter ironies that might be instructive if they weren’t so often forgotten. For one, Yale is named for Elihu Yale, a governor of the East India Company, one of the world’s first multinational corporations, which acquired the island of “Singapura” for the British Crown in 1812.

For another, Yale missionaries in Singapore and China a century later pursued “the evangelization of the world in this generation,” a goal of the American Student Volunteer Movement for Foreign Missions, whose archives rest, fittingly, in the Yale Divinity School. Yale’s would-be evangelists in China parented future Yale missionaries of a different kind: Both Henry R. Luce, co-founder of Time magazine, herald of the American Century in the 1940s, and John Hersey — whose novel The Call depicts Christian missionaries’ blindness to host cultures’ alien cultural depths — were born in China to missionary parents near the turn of the century.

Another century later, in 2003, Yale “missionaries” figured significantly in the design and prosecution of the Iraq War: President George W. Bush; Vice President Dick Cheney (a Yale drop-out, but still,…), Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz, (who, as a Yale professor, had taught a student named I. Scooter Libby, a future top Cheney aide); “axis of evil” White House speechwriter David Frum; and the neoconservative polemicist Robert Kagan (shown here preening about American power and being flattened by French Foreign Minister Dominique De Villepin).

In 2011, other Yale professors and their National University of Singapore counterparts sat in a mansion on a hill atop New Haven, designing a curriculum for Yale-NUS College, a “new community of learning.” That community’s first president, Yale comparative literature professor Pericles Lewis, declared that he was witnessing “the liberal arts experience made manifest” and prophesied “a place of revelatory stimulation” in the campus that Singapore was building on the other side of the world.

Skeptical of such prophesies and resentful at not having been consulted or even informed about Yale-NUS before its contractual commitment was a fait accompli, most Yale faculty at a meeting in New Haven passed a resolution warning that liberal education would be hobbled by Singapore’s “lack of respect for civil and political rights.” The American Association of University Professors sent a public letter to the Yale community and to 500,000 American professors expressing its “growing concern about the character and impact of the university’s collaboration with the Singaporean government…. In a host environment where free speech is constrained, if not proscribed, faculty will censor themselves, and the cause of authentic liberal education, to the extent it can exist in such situations, will suffer.”

Yet Yale’s trustees and administrators and some faculty marched jauntily into the clutches of Singapore’s structures and strictures. Some trustees held material interests in Singapore, as I reported at the time. As a tightly-run, relatively safe port in the storms of global capitalist exploits, Singapore welcomed the Yale investors as advisers and officers of its sovereign wealth fund, the Government Investment Corporation, chaired by the prime minister, and Temasek Holdings, which designated Yale trustee Charles Goodyear IV as its CEO in 2009.

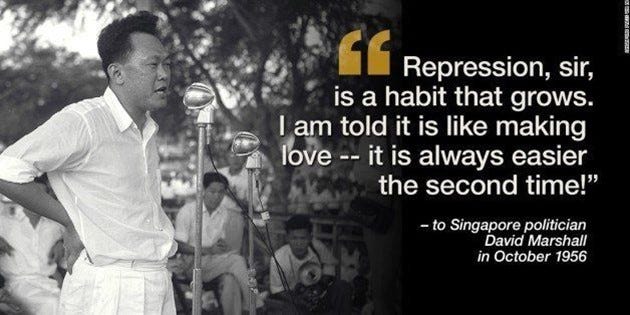

Another trustee, Fareed Zakaria, sketched the ideological interests in The Future of Freedom, praising Singapore’s model of state capitalism and even Lee Kuan Yew, its brutally authoritarian, racist ruler.

Yale President Richard Levin, an economist and apostle of a neoliberal, “World is Flat” vision, believed that the new college would enhance and enrich Singapore as a global capitalist hub with a humanist global management and investment ethos that deflects nationalist, authoritarian undercurrents.

But those swift, dark undercurrents have resurfaced with a vengeance against neoliberal gambits and dreams. Authoritarian state-capitalism is rising, not only in East Asia. Even Britain may become China’s virtual island colony off the coast of Europe, somewhat as Hong Kong and Singapore became Britain’s island colonies off the coast of Asia.

In 2013, a year after the Yale faculty resolution opposed collaboration with Singapore, former Harvard President Derek Bok told me that a “run-in” with Lee Kuan Yew years earlier had convinced him not to trust authoritarian rulers who ride the golden riptides of global finance, communications, labor migration, and consumer marketing, using state coercion to enforce the cohesion that their societies once drew from Confucian, Islamic, or even Western colonial traditions but that they’re losing to global capitalist inequities, escapism, and consequent social crises.

Rulers in Kazakhstan and Abu Dhabi and other countries have also tried to harness liberal education to finesse the brutality and hypocrisy of “go-go” economic development, seeking American colleges’ imprimaturs and instruction in the “critical thinking” and felicity in writing and speaking that a liberal education can impart to their investors, managers, and spokesmen. Recalling how Lee Kuan Yew invoked “Asian values” to justify imprisoning an officer of the Harvard Club there, Bok told me that “Nothing in that experience would tempt me to try to establish a Harvard College in Singapore.”

Reinforcing such skepticism in 2015, John Berthelsen, editor of the independent website Asia Sentinel, reported that Lee Kuan Yew’s son, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, speaking at a ceremony with Yale President Levin and Yale-NUS president Pericles Lewis inaugurating the new college, warned that education there “cannot be a carbon copy of Yale in the United States if it is to succeed. Instead, it has to experiment and adapt the Yale model to Asia.”

An irony in Lee’s warning hasn’t escaped Kenneth Jeyaretnam, former secretary general of Singapore’s opposition reform party, who tells me that “The Singapore Gov thought that it could have the trappings of a world-class liberal arts college without the freedom that goes with it, and that it could be tightly managed and spun to show the superiority of Asian values. It didn’t work out that way.”

Lee’s and his father’s invocations of “Asian values” veiled their narrowly instrumentalist, meticulously repressive policies: In 2013 a five-part Wall Street Journal series documented its abuses of migrant Chinese bus drivers, a paradigm of how it treats rights-less migrants who are one-third of its population. The country’s 2014 Gini coefficient, which measures income inequality, is 0.478, one of the widest in the world. The Economist magazine, hardly an anti-capitalist or human-rights organization, publishes a rigorous Democracy Index that ranks that Singapore down with Liberia, Palestine, and Haiti on its measures of political freedom.

Reporters Without Borders’ index of press freedom in 180 countries currently ranks Singapore near the bottom – 160th, below Belarus and Sudan, its lowest ranking in the ten years I’ve watched it drop down the list. The organization’s Index classifies Singapore as “very bad,” noting that “Despite the ‘Switzerland of the East’ label often used in government propaganda, the city-state does not fall far short of China when it comes to suppressing media freedom. Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong’s government is always quick to sue critical journalists, apply pressure to make them unemployable, or even force them to leave the country.”(Afghanistan’s press-freedom rank was 122, not yet updated since the U.S. departed, but it was well above “sophisticated” Singapore’s 160.)

The prime minister and ruling People’s Action Party have a long record of using fine-spun, Kafkaesque legalism to block freedoms of expression. Jothie Rajah’s invaluable Authoritarian Rule of Law describes their methods. Even university faculty and opposition-party leaders who speak out have been convicted by Singapore’s judiciary, bankrupted when they couldn’t pay the exorbitant fines, and, in some cases, effectively exiled.

Small wonder that Yale-NUS has been kept ever-more tightly in its paymaster Singapore’s pocket. The “Yale” in its name designates merely a hired consultant. As of 2025, even that name will be gone. The many students and professors who feel betrayed by having been admitted this year under false pretenses to a college that will cease to exist after their graduation in 2025 are protesting vigorously, but to no avail.

A comprehensive, Sept. 7 Yale Daily News story reports Singapore’s claim, seconded by former Yale President Richard Levin that the closure reflects only financial, not political problems. But Levin believes that the financial problems were surmountable. Some Singaporeans consider Yale-NUS an objectionably elitist enclave, with too many international students (approximately 40 percent of the student body), but opposition-party leader Jeyaretnam tells me that “elitism doesn’t seem to have been an issue, since 14,000 students signed the petition opposing Yale-NUS’ closing.”

Part of Singapore’s reason for dismissing American pedagogy is “navigational” in a geopolitical sense: Lee Hsien Loong likens his country to a small but doughty craft breasting powerful riptides of global economics and politics. As Beijing and Washington vie for influence in East Asia, Foreign Policy magazine reports that “China… is working hard to influence Singaporeans to take a more accommodating position toward Beijing.” Most Singaporeans and rulers are ethnically Chinese and regard China more favorably than do people in Malaysia, Indonesia, or Australia. Singapore’s removal of Yale may be what it considers a modest concession to China and a way to control the college ever more tightly amid the sea change.

But a deeper reason for Singapore’s expulsion of Yale is the same one that’s been given to justify America’s expulsion from Afghanistan: For all its glitter and wealth-generating capacity, American liberal capitalism has been undermining itself with manic speed, along with the civic-republican institutions, beliefs, and liberal education that have given the system its legitimacy. Today’s ubiquitous, intrusive casino-like financing and algorithmically driven consumer marketing are groping, goosing, intimidating, surveilling, addicting, stupefying, and indebting so many millions of Americans that the United States has less and less of value to export to Afghanistan or Singapore.

As I reported in Dissent magazine in 2018, the private-equity baron Stephen A. Schwarzman has donated US$150 million to Yale, his alma mater, to transform its historic Commons into a hive of junior-business start-up platforms, performance spaces, and lounge areas, all of it renamed the Stephen A. Schwarzman Center. You don’t have to believe that Afghanistan will be better off for spurning such glitter, or that Singapore will be better off for repressing criticisms of its lockstep discipline, to acknowledge that Santayana’s vision of the American as “an idealist working on matter” and a bearer of the requisite civic virtues has been hollowed out by Americans’ obsessions with buying and consuming “matter.”

Unable or unwilling to do for New Orleans of Detroit what we couldn’t for Kandahar or Kabul, Americans are losing their mastery of the arts and disciplines of their own domestic nation-building and democracy promotion, along with liberal education’s great conversation across the ages about lasting challenges to politics and the human spirit.

Yale excelled at these pursuits in 19th and early 20th century America, but it has lost its way. We’ll need to renew our own civil society’s institutions, including its colleges, as “places of revelatory stimulation,” where the experience of liberal education is “made manifest” more vividly than it has been in most of our lifetimes.

Jim Sleeper is a retired lecturer in journalism and political science at Yale College in New Haven, Conn.