The Downside of Diversity

from WSJ

The Downside of Diversity

On campus, identity politics has become a dogma that damages independent thinking and the pursuit of truth.

By Anthony Kronman – Aug. 2, 2019

“Diversity” is the most powerful word in higher education today. No other has so much authority. Older words, like “excellence” and “originality,” remain in circulation, but even they have been redefined in terms of diversity.

At Yale, where I have taught for 40 years, a large bureaucracy exists to ensure that the university’s commitment to diversity is rigorously enforced—in student admissions, faculty hiring and curricular design. Yale has an Office of Diversity and Inclusion, a Dean of Diversity and Faculty Development, an Office of Gender and Campus Culture and a dizzying array of similar positions and programs. At present, more than 150 full- time staff and student representatives serve in some pro-diversity role.

Yale’s situation is far from exceptional. “Diversity and inclusion” is a dogma repeated with uniform piety in the official pronouncements of nearly every college and university. At Dartmouth, the Office of Pluralism and Leadership “engages students in identity, community and leadership development, advancing Dartmouth’s commitment to academic success, diversity, inclusion and wellness.” The University of Michigan proclaims that “diversity is key to individual flourishing, educational excellence and the advancement of knowledge.” At the University of Oklahoma, students are required to complete a mandatory “Freshman Diversity Experience” by the end of their first semester.

That diversity should be a value seems beyond dispute. The existence on campus of a range of beliefs, values and experiences is essential to the spirit of inquiry and debate that lies at the heart of academic life. Who wants to go to a school where everyone thinks alike?

But diversity, as it is understood today, means something different. It means diversity of race, ethnicity, gender and sexual orientation. Diversity in this sense is not an academic value. Its origin and aspiration are political. The demand for ever-greater diversity in higher education is a political campaign masquerading as an educational ideal.

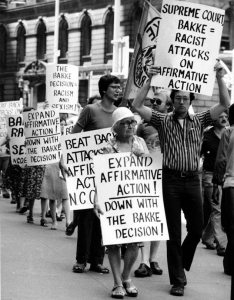

The demand for greater academic diversity began its strange career as a pro- democratic idea. Blacks and other minorities have long been underrepresented in higher education. A half-century ago, a number of schools sought to address the problem by giving minority applicants a special boost through what came to be called “affirmative action.” This was a straightforward and responsible strategy.

But in 1978, in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, the Supreme Court told American colleges and universities that they couldn’t pursue this strategy directly, by using explicit racial categories. It allowed them to achieve the same goal indirectly, however, by arguing that diversity is essential to teaching and learning and requires some attention to race and ethnicity. Schools were able to continue to honor their commitment to social justice but only by converting it into an educational ideal.

The commitment was honorable, but the conversion has been ruinous. The effects of racial prejudice have always been the greatest slur on our commitment to democratic equality. But the transformation of diversity into a pedagogical theory has weakened our democracy by undermining the common ground of reason on which citizens must strive to meet. The crucial confusion is the equation of a diversity of ideas with diversity of race, ethnicity and sexual preference. This has several pernicious effects.

One is that it encourages minority students, and eventually all students, to think that a departure from the beliefs and sentiments associated with their group is a violation of the terms on which they were admitted to the university. If students contribute to the good of diversity by expressing the racially, ethnically or sexually defined views that members of their group are expected to share, then a repudiation or even critical scrutiny of these views threatens to upset the school’s entire educational program. It takes special nerve for an African-American student to defend inner-city policing or a gay student to support the baker who refuses to make a wedding cake for a same-sex couple.

For this program to work, it is essential that students remain in the corners to which they have been assigned. Indeed, it is not enough merely to recognize that the members of each group contribute some distinctive dimension to their school’s diversity. To reassure those whose groups have been the victims of social prejudice and discrimination, extra deference must be given to their life experience. The members of more privileged groups must be taught to “check their privilege,” and the identity of minority students must be treated as a possession that no one else may “appropriate,” in however well-meaning a way.

The upshot is that students are lauded for the beliefs and feelings they bring to their school on account of their separate identities, rather than being reminded of what they all stand to gain by being there—the inestimable privilege of joining in a rational inquiry that subjects every one of their sentiments and beliefs to the same rigorous demand for explanation and justification.

In politics, group solidarity is a condition of success. But in college, it is an obstacle to the pursuit of what Walt Whitman colorfully called the “idiocracy” of individual temperament and expression that sets each of us apart from every other. The politically motivated and group-based form of diversity that dominates campus life today discourages students from breaking away, in thought or action, from the groups to which they belong. It invites them to think of themselves as representatives first and free agents second. And it makes heroes of those who put their individual interests aside for the sake of a larger cause. That is admirable in politics. It is antithetical to one of the signal goods of higher education.

This is one of the things people mean when they say that campus life has become “politicized.” It also helps to explain the culture of grievance that is so prominent there. Examples are legion. At Yale, where the heads of the undergraduate residences used to be called “masters,” students successfully campaigned to have the title changed because it reminded them of an antebellum plantation. Last year, a yoga club at American University was disbanded after complaints that it invited a non-Indian group to perform a dance based on the Ramayana, a classical Hindu epic. At Oberlin, all classes were canceled and a communitywide gathering called when someone dressed in what appeared to be a KKK costume was spied on campus. It proved to be a woman in a blanket.

Grievance is the stuff of political life. In politics, it is normal for one group to highlight its suffering and to demand reparations from another group or a greater share of its power. This is especially true where questions of racial justice are concerned. Here, the temperature is sometimes high enough to melt decorum and goodwill.

Academic disagreements are different. Important ones are often inflamed by passion too. But the goal of those involved is to persuade their adversaries with better facts and arguments—not to bludgeon them into submission with complaints of abuse, injustice and disrespect to increase their share of power. Today, the spirit of grievance has been imported into the academy, where it undermines the common search for truth by permeating it with a sense of hurt and wrong on the part of minority students, and guilt on the part of those who are blamed for their suffering.

The life of the classroom is transformed as a result. It is common to hear complaints that an assigned text is disrespectful of women, blacks, the gender-fluid or some other oppressed or marginalized group. White, male, heterosexual students are often attacked on the grounds that their comments reflect a smug and privileged view of the world. Such complaints are hardly new. I have heard versions of them at Yale for the past 40 years.

Whatever else it may be, the truth is not democratic. We don’t decide what is true by a show of hands.

What is new and discouraging about today’s academic culture is the unprecedented weight that these grievances are given by teachers, students and administrators alike. Even to raise them puts one on a high moral ground that requires all other considerations to be put aside until the grievance has been assuaged by an appropriate act of apology or reform. Raising it amounts to a demand. It brings the conversation to a halt. It converts the classroom from an open space for the free exchange of ideas into a political battleground.

Yet even this does not fully capture the harm that the contemporary understanding of diversity has done to our colleges and universities. The greatest casualty is the idea of truth itself, on which the whole of academic life depends.

Whatever else it may be, the truth is not democratic. We don’t decide what is true in mathematics or history or philosophy by a show of hands. The idea of truth assumes a distinction between what people believe it is and the truth itself. Socrates drove this point home in every conversation he had. It might be called the Socratic premise of all intellectual inquiry.

A corollary is that I am not entitled to call something true merely because I believe or feel it to be true. My beliefs and feelings are not trumps that I can play in a debate about the truth of any claim. It wrecks the Socratic adventure to say that as a (female, black, Jewish, Muslim, gay or trans person—fill in the blank) I see things from a point of view to which others have no access and that my perspective is authoritative because I have been the victim of hatred and mistreatment.

In a genuine search for the truth, my feelings and beliefs must be subjected to the same review as everything else. They may be a source of information and an indication of how strongly I hold the view I do. But they can never, by themselves, validate my position.

For college students, the search for truth is important not because reaching it is guaranteed—there are no such guarantees—but as a discipline of character. It instills habits of self-criticism, modesty and objectivity. It strengthens their ability to subject their own opinions and feelings to higher and more durable measures of worth. It increases their self-reliance and their respect for the values and ideas of those far removed in time and circumstance. In all these ways, the search for truth promotes the habit of independent-mindedness that is a vital antidote to what Tocqueville called the “tyranny of majority opinion.”

The relentless campaign for diversity and inclusion on campus pulls in the opposite direction. Motivated by politics but forced to disguise itself as an academic value, the demand for diversity has steadily weakened the norms of objectivity and truth and substituted for them a culture of grievance and group loyalty. Rather than bringing faculty and students together on the common ground of reason, it has pushed them farther apart into separate silos of guilt and complaint.

The damage to the academy is obvious. But even greater is the damage to our democratic way of life, which needs all the independent-mindedness its citizens and leaders can summon—especially at a moment when our basic norms of truthfulness and honesty are mocked every day by a president who respects neither.

Tocqueville was an enthusiastic admirer of America’s democracy. He thought it the most just system of government the world had ever known. But he was also sensitive to its pathologies. Among these he identified the instinct to believe what others do in order to avoid the labor and risk of thinking for oneself. He worried that such conformism would itself become a breeding ground for despots.

As a partial antidote, Tocqueville stressed the importance of preserving, within the larger democratic order, islands of culture devoted to the undemocratic values of excellence and truth. These could be, he thought, enclaves for protecting the independence of mind that a democracy like ours especially needs.

Today our colleges and universities are doing a poor job of meeting this need, and the idea of diversity is at least partly to blame. It has become the basis of an illiberal and antirational academic cult—one that undermines the spirit of self-reliance and the commitment to truth on which not only higher education, but the whole of our democracy, depends.