The High Rider of the Gay Divide

originally released 5/27/2019

Timothy Clark: Fifty years. Seems unreal, preposterous, unlikely, and ultimately fortunate to survive a half century. I mourn Allen Cromer. I mourn Terry Green. I mourn Army Odabashian. I mourn Jerry Glover.

Those of you who completed the online class survey last year [N.B. 2018] will recall that it contained an unusual query:

“Our classmates Jeff Horton and Bill Stanisich are writing an essay for the Classbook on the experiences of gay members of the Class of ’69 (and classmates who knew them), during our Yale years … and/or since. If you would like to be interviewed for this essay, or just want to share ideas and experiences, click here to send an email.”

About ten gay classmates responded to Bill and Jeff. They sent in their memories of being clandestinely gay at Yale; I have quoted from their accounts below. A few straight classmates emailed too. I wrote that I was straight but had an impression of the late Jerry Glover I wanted to submit. Jerry, who died in 1982, had been a friend of mine, not a close friend, yet I had an intense feeling that he would be important to the project that Horton and Stanisich were organizing. The two agreed.

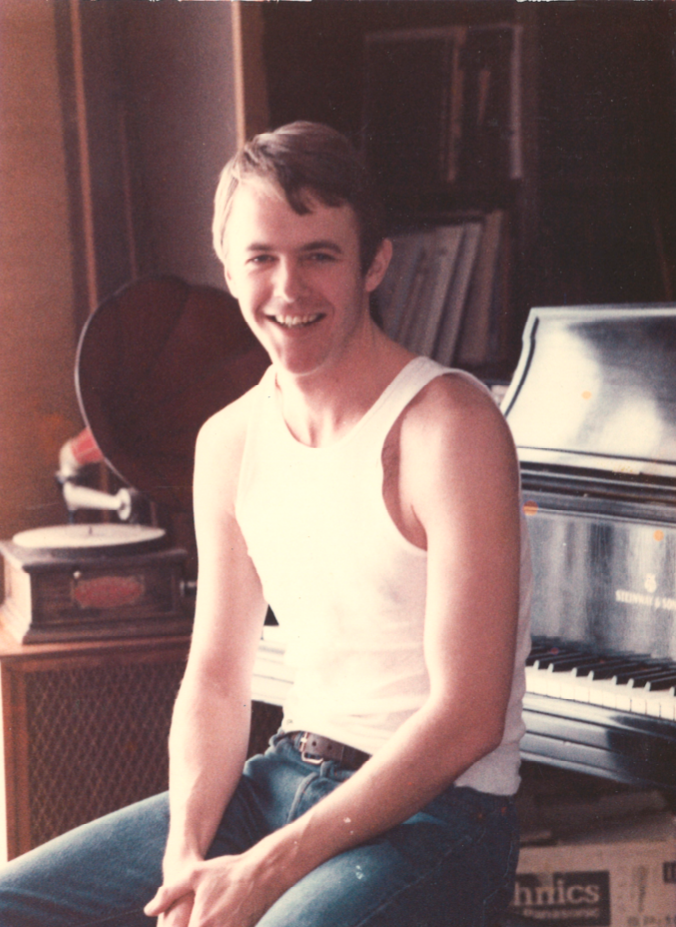

Charles Carroll (Jeremy) Glover IV—quel nom de Yale!—was originally a member of the Class of 1968. In his sophomore year Jerry had dropped out, and he picked up again with our class in the fall of ’66. Living in Ezra Stiles, Jerry would join a circle of friends that included Bill Stanisich and Jeff Horton, and also Tim Clark, David Joralemon, and Cleve Morris.

As a sophomore across campus in Silliman, I didn’t know any of these vibrant young men. Then again they were only just starting to know themselves. The five Stiles survivors are much wiser today. I think of them as a Greek chorus in a classical tragedy about Jerry Glover.

Jeff Horton: What was it like to be gay at Yale? I can sum it up in one sentence: It was better than being gay at La Habra High School (in Orange County, California) in the early 1960s.

Cleveland Morris: In those days, gays were routinely arrested and jailed. Except in exceptional circumstances, gay men were shunned. Not only was homosexuality (even between consenting adults) illegal in 49 of the 50 states at the time, it was deemed a mental disorder by the American Psychiatric Association, often treated by shock aversion therapy. Show us pictures of naked men and zap us with electric shocks until we vomited, that should “cure” us!

David Joralemon: Starting in 1965, R. Inslee Clark [director of admissions] destroyed the stranglehold of New England WASPS on Yale. In streamed people of different nationalities, races, religions, geographical backgrounds, income levels and life experience. We were part of that flood. For better and worse we came of age in that context.

Jeff Horton: I arrived at Yale in 1965 as a high-achieving, politically conservative “best boy” determined to hide my homosexuality behind a curtain of laudatory accomplishments and Ayn Rand/Goldwater orthodoxy. I left Yale in June 1969 as a vaguely ambitious, politically ambivalent, mildly rebellious, and SEXUALLY ACTIVE gay young man.

Cleveland Morris: Looking back now, I think it’s curious that there were so many of us together at Ezra Stiles. I wonder if our proportions were reflected in the other residential colleges, or if our setting was unusual.

I met Jerry Glover when we both joined Fence Club in 1967. Fence, you may remember, was the prep school boys’ fraternity.

Where I went to school—an Episcopal boarding school in New Hampshire—there weren’t any homosexuals so far as we knew. We certainly joked about them, though. A kid was called “Mo” or “Homo” if he was a little unusual. You could nuzzle a smaller boy from behind and get a big laugh. A guy named Roy, as straight as you please, was affectionately known as “Fag.” Three or four of the masters (teachers) were mocked for their effeteness behind their backs, and sometimes to their faces. None of this constituted a slur, we thought. What did we know 50-plus years ago? Little bullies that we were.

When we were exposed to peers of different backgrounds in New Haven, I and my friends were more circumspect. The juvenile name-calling had stopped, and was replaced by the occasional roll of the eyes. We still didn’t know any homosexuals.

Fence Club was not as diverse as the colleges. Around the pool table at Fence or by the polished, wooden bar, Jerry Glover didn’t particularly stand out. We all more or less dressed alike. We spoke the same confident language. OK, he was glossier than most, a bit smoother and funnier, with that big wicked smile of his. A handsome fellow, to be sure.

Jerry and I took a liking to one another. Whenever I’d see him, I’d start to smile, and he likewise, because one of us was about to make a quip. But our friendship, sparkling though it seemed, reminds me today of a one-way mirror. Jerry saw me plainly through the glass, while I saw only my preppy reflection.

Cleveland Morris: We were always judging people: who came from a more elite secondary school, who’s smarter, whose family is richer, who had the best connections. On the surface of things, Jerry ranked high by any of these standards. His patrician heritage, his family’s wealth, his intelligence and talent, his striking physical beauty all made him stand above the rest. He was Oscar Wilde and Lord Alfred Douglas rolled into one.

But there was one wild card that could have canceled out all the others: homosexuality. Since society and the law treated us as crazy criminals, gay men growing up in the ‘50s and ‘60s became adept at “passing.”

An anonymous classmate: The gay community, such as it was, existed in a secret, subterranean universe that dared not let itself be known and had no contact with the rest of undergraduate life. My undergraduate experience living a deeply compartmentalized life set a pattern that I followed as I entered a profession—law—that was as fundamentally hostile to homosexuality as Yale was. But I don’t blame Yale for any of this. It was only because Yale celebrated the kind of man I knew I wasn’t that my Yale experience was challenging. I am as conflicted today about being gay as I was when I was an undergraduate.

Bill Stanisich: I didn’t go through Yale cowering at the slurs others might have been saying about me. Clearly it happened—as in all the male environments. But it was most dangerous when directed at oneself or other gays. The phrase for this is internalized homophobia. One example: Jeff Horton and I had a mutual gay friend who was obsessed with the subject of who else at Yale might be gay. He kept a list of who was gay, in other words, those classmates who had been reported to him by others, and who were proved to have had mutual sexual experiences. He had regulations: the person had to have had sex, including orgasm, with a classmate. Our reporter kept the list in Russian, as if the CIA couldn’t read Russian.

David Joralemon: As in any culture which marginalizes a group, like-minded souls find their sanctuaries and safe houses. For people like us it was the Arts and Humanities, the Elizabethan Club, literary circles, the steam room at certain hours, the Glee Club and singing groups, a certain off-campus drinking establishment, a quiet and out-of-the-way section of the library, or the classes of understanding professors. New York was close enough to be a refuge and anonymous place where some could be themselves without fear. The macho gay men, and there must have been some of them, could hide behind Bromances and with care never be discovered. For some gay people, celibacy was the refuge.

Timothy Clark: I have tried to remember the furtiveness of our undergraduate years. I remember one had to have a woman to dance with if you wanted to dance. You had to have a woman to go to the prom. I never availed myself of certain bathrooms on campus but I knew of them.

Jerry Glover’s girlfriend—I guess I should put quotes around her—was a Sarah Lawrence student named Bobbie. As I remember, she was tall and slim with dark hair. Gold bracelets and earrings. A throaty, intelligent laugh. In our junior year when we’d have a dance at Fence, I’d see Bobbie and Jerry out on the floor twirling. A live band with horns played Motown songs. Jerry was able to maintain a gentlemanly attention on his date while keeping tabs on the action on the floor.

One time I wore a pair of green leather pants. They weren’t actually leather, more like naugahyde, and shiny. They pushed the envelope of what to wear at Fence. The pants were tacky, but Jerry loved them. I learned later he was crazy for costumes.

My date and I began to prance from side to side along with the beat, kicking our free legs straight up into the air, like drunken sailors. Eyes shining in delight (Bobbie watching too, over Jerry’s shoulder), Jerry cried, “Legs!…Legs!”

After that, he always greeted me on campus as “Legs,” which I didn’t mind at all. Not at all.

David Joralemon: How many of us hid from ourselves and from our fellow travelers, whether because of the shackles of self-hatred or out of simple fear of being “outed” and ostracized by our friends and classmates? How quaint the word “outed” now seems and how terrifying the prospect was then. It clearly still has power over some. I wonder how many still enjoy their well-decorated closet after 50 years?

Bill Stanisich:One day our mutual tabulator told me that Jeff Horton was gay; he had met the criteria for the “list.” I protested to this classmate that now he had gone too far. But after dinner that night, Jeff and I stayed down in the buttery in Ezra Stiles while I played the piano and we circled the subject. It turned out that Jeff was indeed gay and I had been described as having “so many partners that I could not remember them all.” I felt malice.

—

Jeff Horton: I discovered pot and became something of a hippy. I discovered that the upper class prep school boys were not any smarter or better than I was, just richer. I developed a rudimentary cultural awareness that included opera and classical music, classic American movies (shout out to the Yale Film Society!), and…I had sex with men!

But equal in importance was having gay friends. That was huge! We weren’t actually “out” to each other, but it was clear to all of us. David Joralemon and I were freshman roommates and we never once in four years mentioned being gay. Ditto for Timothy, Cleveland, and the others. We just basked in the awareness of our shared orientation. I did have a couple of friends with whom I was open, especially Bill [Stanisich] from San Francisco.

Cleveland Morris: One bold exception to this rule of concealment and double identity was Jerry Glover. While he never actually took out a full-page ad in the Yale Daily News proclaiming his sexuality, he never sought to conceal it. He just didn’t seem to care what anyone thought!

When he took up with a cast member from the revolutionary Off Broadway show, The Boys in the Band, he would regale one and all, closeted gays and defiant heteros alike, with tales of his party-going adventures in New York City. “And you’ll never guess who arrived at midnight… Liberace!” And we’d all howl!

Bill Stanisich: …Those tales of cast parties in New York. He said it in front of jocks, preppies, other gays, anybody. He loved being outrageous. Jerry was flamboyant and known by a large number of classmates. He might have been the most open classmate we had. He crossed the gay/straight boundaries at Yale, and it did not matter which side of the divide he was from. He lived life to the full and brought intense pleasure to others.

Although marijuana was an illegal and rather scary unknown to me, many at Yale were trying it. I wanted to lose my virginity, so to speak, but who to ask? So when Jerry and I were talking one day, I circled around the subject.

Being a theater major and skilled at many roles, Jerry also could read an audience when he looked beyond the footlights. Abruptly he invited me to come to his room the next Saturday night, where he promised to turn me on.

Saturday came, a warm and dark night in May. I remember feeling nervous as I walked across campus to Ezra Stiles, a college I’d never visited before. The daring architecture and glitzy concrete on its exterior had quite a different sense than the straight red bricks of Silliman.

I had Jerry’s room number, but didn’t know the entryways. I found myself walking on a retaining wall outside of the dark college, as I peered down into the brightly lit wells of the ground-floor rooms. All at once I stumbled and twisted my ankle painfully. A bad sign. The evening was not going well.

Eventually I found his room. Jerry and a couple of others were waiting. Derek Huntington was one, another guy from Fence. Were there candles? Music? Surely the lighting was low, and in retrospect I’ll paint a Mephistophelean smile on my friend’s face. Jerry showed me how to smoke. He didn’t laugh when I coughed.

It turned out to be one of the most enjoyable nights of my college career. Having been told or maybe I read somewhere that pot numbed pain, I had the proof in my swollen ankle, which didn’t hurt at all during my light-headed walk back to Silliman.

Cleveland Morris: Jerry and I were both active participants in the Ezra Stiles Dramat. I even directed him once and remember going to a Sunday brunch with my parents and his parents at the house of one of the top university officials. I remember meeting his formidable grandmother there, who always referred to her late husband as “Glover.”

I also met Jerry’s mother on several occasions and I believe she once gave a song recital at Yale, perhaps at Ezra Stiles. Was she a strong influence on Jerry’s artistic pursuits?

Jeff Horton: I knew he was from a prominent family in Washington D.C. Sometimes I felt a little clumsy and plebeian around him, although he was always gracious and friendly. Did his background enable him to be open and unafraid? Gradually my awe of Jerry diminished and I came to see him more as just another friend.

Bill Stanisich: I invited Jerry to my parents for dinner and he showed up in a lace blouse. Some drinks later plus dinner and they enjoyed him immensely. It was good for them.

Timothy Clark: Just before graduation, Jerry invited several of us to spend a few days relaxing at his grandfather’s house near Cape Cod. My dearest memory is that Jerry taught me how to eat a whole, boiled lobster.

At college I knew nothing of Jerry’s social background except that it must be congruent with mine. Recently I gathered information on the internet about his high-powered pedigree, through which ran a vein of artiness.

The first Charles C. Glover, the man who built the family fortune, has his own Wikipedia entry. “Charles Carroll Glover (November 24, 1846 – February 25, 1936) was a banker and philanthropist who made major contributions to the modern landscape of Washington, D.C. in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He was President of Riggs Bank, an effective advocate of urban beautification in Washington under the influence of the City Beautiful movement, and a generous donor of land and money for Washington’s parks and monuments.” Glover the first was said to be “both a businessman and a poet.”

Jerry’s grandfather, Charles C. Glover Jr., a graduate of the Yale class of 1910, was a Washington banker too. According to his obituary, “He was at various times president of the Corcoran Gallery of Art, The Metropolitan Club, and the Yale Club of Washington.”

Charles C. Glover III (Class of 1940) was chairman of the Daily News, a member of Skull and Bones and a member of Phi Beta Kappa. A well-connected D.C. lawyer, Jerry’s father was active in civic charities and led the National Symphony Orchestra’s board of directors. Virginia Glover, his mother, was a semi-professional concert singer during the years when Jerry was growing up. She served as president of the Washington National Cathedral Association.

Now that is a tall order even by Fence Club standards. Jerry Glover had lots to measure up to, assuming he felt the pressure to measure up. Curious about his upbringing, I tried to find Everett, Jerry’s only brother, who was a class behind us in Davenport, but learned that Ev had died in 2016. According to the clippings, there was a younger sister too, who lived in California.

We do know that after graduation Jerry set his sights on a career in the theater, and that he had enough money to entertain himself in San Francisco and New York—the places where the gay scene was busting out.

Jeff Horton: We were good enough friends and without any sexual attraction, so that after graduation we agreed to drive from Yale to San Francisco in his Volvo. Jerry was going out to study acting at A.C.T., a highly competitive program. I don’t remember a lot about the trip. I think we took acid in the woods of Montana. We stayed in cheap motels. He was excited to get to San Francisco, and I made my way on down to L.A.

David Joralemon: The epochal changes which destroyed the “Leave It to Beaver” world that many of us grew up in the 1950s were beginning to overwhelm the nation. There were the anti-war movement, anti-segregation protests, women’s liberation, and the sexual revolution among all the other social upheavals that came to a boil during our undergraduate years. The Woodstock Festival was in 1969. The Stonewall riots happened just a few weeks after graduation.

Bill Stanisich: In San Francisco in the early ‘70s I ran into Jerry on the nude beach at San Gregorio and asked him to come to see Donizetti’s Elixir of Love with the new tenor, Pavarotti. The audience went wild and he was thrilled to see Pavarotti before his Met debut.

We also saw Beverly Sills as Cleopatra in the Handel Julius Caesar. Jerry was like a little kid. We got cheap standing room tickets and he was overjoyed with her runs and trills and outlandish costumes. He had a huge capacity for joy. Although not my type, Jerry was beautiful to look at. Were his eyes lavender or was that some piece of artifice?

Cleveland Morris: I saw him a bit in NYC in the ‘70s when we had both settled in Greenwich Village. He had a bare-bones loft, which he eventually redid in a stunning manner. I had continued to work in the theatre, but he had switched his allegiance to photography. His personality and background just didn’t suit themselves to the humiliating and uncertain life of an actor starting out in NYC.

In my early days in New York I spent a couple of nights in his loft. One morning I woke up to find Jerry in bed in the arms of a man who was his… Identical Double! Now I know the meaning of narcissism, thought I, and decided three’s a crowd.

Bill Stanisich: I used to have a friend who lived in the Village. He said that Jerry would come into a bar, order a beer, scan the premises with the air of someone who had deals breaking on the West Coast, shake his blond mane, and walk out. Jerry was generous and fun but sometimes he could be a first-class snot.

Bill Stanisich: The HIV calamity is our holocaust. We preceded it by only a few years and the class as a whole has lost maybe two dozen men—maybe more. We had a Stiles member whose family went to some lengths to deny his illness—even though at least two people visited him at the end and it was obvious. “He died of an aneurism!” his sister proclaimed.

That’s my main regret about our time at Yale. Reading the obituaries from the nearly half century since our graduation, one would think that almost no one perished from the HIV epidemic. I would never “out” someone whose family maintained silence about an HIV death, but I do indeed know of classmates who died of HIV and whose families refused to acknowledge the fact. It pains me greatly to think of friends who might have been supported by classmates if they had known. To face the epidemic alone, alienated from the friends who meant so much in one’s youth, is doubly tragic.

Jerry and I were not in touch after graduation. I heard he was living in New York. I must have known that he had come out, and I must not have been totally surprised to learn that he was gay.

My apartment in the 1970s was on Perry Street in the Village, just north of the Christopher Street subway station. When I walked home from the subway, men on the street would grin and smack their lips at me, as if to pay me back for my cruel behavior in boarding school. One night I was very discomfited to hear, through the thin walls of the apartment, two male voices straining for orgasm at the same time.

I got married. My wife and I and our infant daughter lived on 10th St. in a different part of the Village. One day I saw Jerry seated on the subway. He wore a buckskin jacket. He was still handsome, but also rather ratty-looking and pale. I think he was sick. Do you remember how Jon Voight looked in the sad part of Midnight Cowboy? That look. He wasn’t well.

He glanced up and saw me. I gripped the pole in the rocking subway car. The lighting was bad, graffiti on the gray metal wall behind him. I didn’t know what to say to him, nor he to me. It’s strange to know someone well enough to be able to read his mind at the same time he’s reading yours. We saw into each other plainly then. No more mirrors. Goodbye, Jerry.

Timothy Clark: I stayed at Yale in one capacity after another until 1981. I attended the first furtive meetings of the Gay Alliance at Yale (GAY), and I attended the 25th anniversary of that at the Commons where the President apologized for the homophobia at Yale. I am a member of Yale GALA as it is called now and have had unbelievably healing experiences in recent years on campus.

David Joralemon: It would take another generation and massive changes in culture and individuals to make Yale the gay-friendly place it later became. Turning an old, time-worn enterprise in a new direction was difficult, but reorient itself it did.

Bill Stanisich: After much thought and experience, it seems clear to me that being gay is no more notable than being right-handed or left. The only way to accept oneself (and others) is to break the bond of self-recrimination.

Jeff Horton: Some years after college I began my real liberation and self-definition by entering into what would be a lifelong connection with African Americans and the African American community. This connection began carnally with favoring Black men, but soon included teaching in a Black high school, settling down with a Black boyfriend and his extended family, adopting two little Black boys, and now adoring a little Black granddaughter. As a glance at our family Christmas picture reveals, I am now the oldest member of a Black family, Black by adoption you could say.

The academic breadth I experienced at Yale and the availability of a circle of gay friends gave me the basis for building a mature life that included open self-acceptance and connection with others different from myself. That was what being gay at Yale gave to me. Thank you, Yale.

Cleveland Morris: What I mostly recall about Jerry are the wonderful experiences we shared putting on plays in the Ezra Stiles Dramat and the hundreds of his campy anecdotes that still make me laugh. But now I am trying to wrap my mind around something more fundamental: his ability to live his life freely and authentically, without seeming to give a damn what anyone thought. When most of us spoke in whispers and kept our eyes averted, here was a man who spoke out loud and clear and looked the world straight in the eyes, usually with a smile on his face. How many people have the courage of authenticity at the age of 20 or even as fully fledged adults? Isn’t that the goal of a liberal arts education? Shouldn’t that be the goal of life?

Postscript: I thought we had finished, put our friend to rest, until his sister, Sheilah, responded to my letter.

Sheilah Glover: My father had wanted to name him Jeremy. I’m not sure where he came up with that name. It sounds kind of gay! My parents never had any intention of calling him Charles or Carroll. But then at the christening they caved, and called him Charles Carroll Glover the 4th, poor thing. I suppose there was some family pressure to do so.

Jerry was born first, and he and my mother were extremely close. He loved to hear her sing, and she would take him with her to rehearsals. They were inseparable. One day his kindergarten teacher took my Mom aside and said, “Your son is too effeminate. You need to do something different.” And to our father she said, “You have to play ball with him, take him outside.” My father really wasn’t a ball-playing dad.

It broke Jerry’s heart. My mother thought she was doing something wrong, and so she withdrew. He didn’t know why. He criticized her mercilessly. It was hard for me to watch. But when he became so ill, he forgave her. They had a good cry—there’d been about 30 years of tragic, unnecessary pain.

I remember another pivot point. In 1967 when he was a junior, Jerry was in a car accident. He had a body cast for quite a few months. Jerry had dated girls before then. In fact, on the night of his accident he had just dropped a girl off. But afterwards he came to terms with his sexuality. He had a lot of time to reflect and maybe the accident was a wake-up call. He changed after that—he came out in his own way.

After Yale, in New York, he became passionate about photography. He was doing well; he had some shows. For a while he worked for Aperture magazine. But then I think he fell into dangerous behavior. He was an adventurer, and may have become addicted to the danger. Jerry was an early AIDS casualty before they even called it AIDS. Ahead of the curve again!

My parents were torn about Jerry. My father appreciated the arts, and they were supportive, but Jerry was very independent and non-conformist. They were kind, well-meaning people. My father had a reunion with his Skull and Bones classmates around the time Jerry was ill, and he told them, “I want you to say a prayer with me for my dying son. He’s dying of a homosexual-related disease.” I’m told they all circled and held hands—pretty amazing for the class of 1940.

And now I’m a happily married (28 years) lesbian with an adopted daughter from China who is graduating from N.Y.U. Maybe there is something to the gene theory!

This has been a cathartic review and I so appreciate his friends’ reflections. My adored big brother has been gone now for one year longer than he lived—a short but vivid 36 years. I still miss him every day.

As I read this narrative of longing, belonging, outsider/insider, and discovery, I relate deeply, albeit along a different divide: my Jewishness. Along the way I have hesitated, hid out, even doubted my authenticity as a Jew. But I have never loathed myself as a Jew. I appreciate how our gay classmates grew to have faith in themselves, became confident in their sexuality, and resolved to stop concealing their personhood.

For much of my time in New Haven I was blind to the possibility that fellow Yalies were gay; by graduation I was aware of just one or two classmates who probably were. As my wife Donna will confirm, I’m about the most oblivious man on earth, so it’s no wonder that to me gays on campus were so invisible. But I wonder if gays didn’t sense a phobia so thick and pervasive that it was palpable. At our 40th reunion, I approached a fellow Berkeleyite who deflected my (I thought) friendly question as to whether he was in relationship.

On the other hand, I have a nephew, Class of ’88. While taking a ski lift with him the year he graduated, I asked him how was the women scene in New Haven. “You might ask me about the men scene, ‘cause it’s fantastic!” he replied. He and his beau were married several years ago, have had a beautiful boy conceived, born, and circumcised, and are awaiting a second child. Go, Class of ’88!

I’d end my musings there, but my memory has been prompted back to New Haven during our junior year. A fellow Yalie has recently met a Vassar woman who has refused his advances. In an effort to salve his amour propre , he rationalizes that she must be “a lesbo.” Chuckles all around, although we all know he’s a shmuck. So I contribute to the context of why my fellow Berkeleyite might want to keep mum forty years later.

It’s not that I was outraged and kept silent; I participated in the evil tongue (Hebrew for gossip). Since then, in the big, bad, real world of living values and making choices, I’ve kept my silence when some guy told me he’d been Jewed, and when a taxi driver used the N word to his dispatcher as I squirmed in the back seat. So what the fuck kind of man have I been? I recently stopped a fellow congregant as he was beginning to tell a disparaging joke about blacks. Maybe I’m strapping my balls back on. It feels a lot better than squirming.

Jon Hoffman