The Isthmus For Christmas

Back in the 1950’s, when I was a skinny little kid with a preternatural love of geography, I used to spend long half-hours staring at the maps of the world and imagining myself somewhere out there. It was never difficult for me to look at a brightly colored speck on a piece of paper and to then transport myself to some romantic notion of some different kind of place that was there and not here. Here being the dimly lit room in the small house in my hometown where I found myself each and every afternoon after school with my mother off at work.

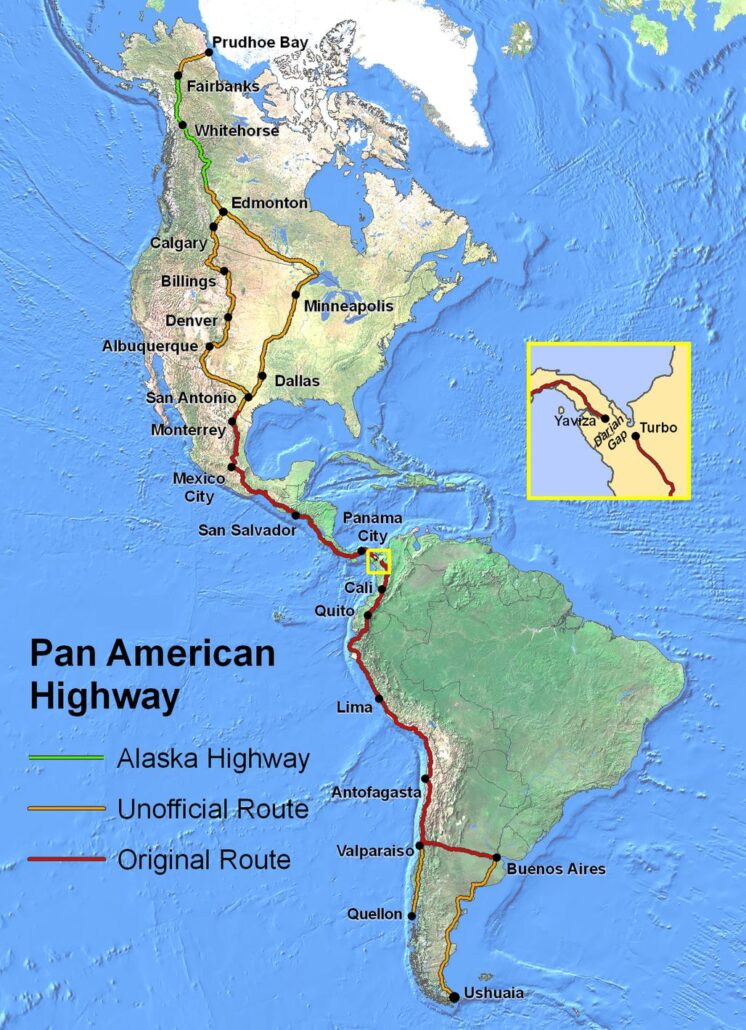

And one of my favorite romantic places to imagine myself being was on the Pan American Highway, that thin red line on the map that connected Fairbanks, Alaska, with Tierra del Fuego in furthest Argentina.

And one of my favorite romantic places to imagine myself being was on the Pan American Highway, that thin red line on the map that connected Fairbanks, Alaska, with Tierra del Fuego in furthest Argentina.

And why wouldn’t it be romantic? After all, this wasn’t some railway in India or some fairy tale lane in Europe. This was an actual road which you could actually get to from right here! There was no need for an ocean liner or an airplane or any other of those fantastical conveyances which as a little kid I could never even begin to conceive of affording. Just think of the romance, the freedom, of having an actual car, of starting out from whatever dimly lit room you were in in North America, and…just…going…

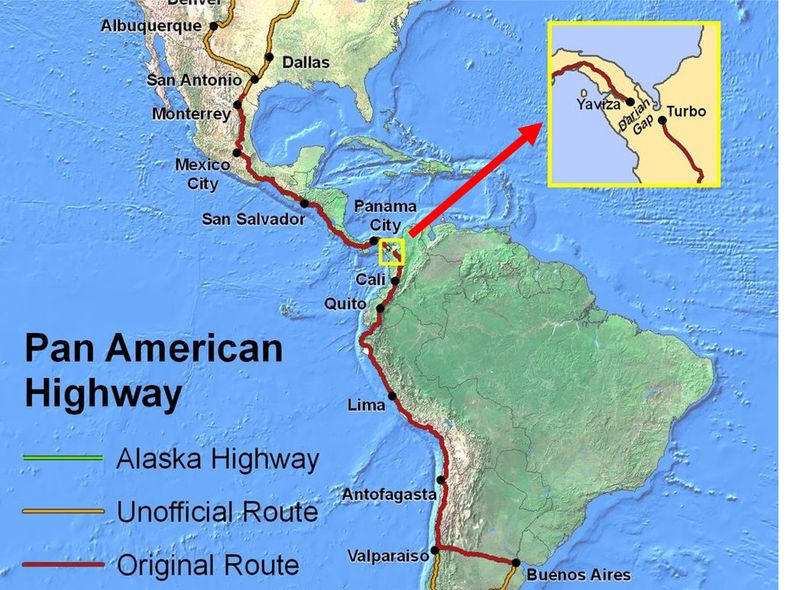

Of course, since I spent a lot of time looking at maps, soon enough I noticed that the Pan American Highway wasn’t really a totally complete red line. No, actually right before it hit South America, right after the Panama Canal, in fact, it was instead a dotted red line, and there was this notation: ‘Under Construction’.

But how could that stop my daydreaming? After all, by the time I wasn’t a skinny little kid any more, by the time I had an actual car to drive and the money to drive it with, by then that wonderful intercontinental road would be complete. By then it would be as common to drive to Paraguay as it would be to drive to Pennsylvania.

And by then, should you happen to be in your car following mine, well by then you would have just been having to eat my Bolivian dust as I sped across the altiplano on my merry way to Antofagasta…

Okay. It was now some forty very odd years later. And I had done a fair bit of traveling in the meantime, having been to Fairbanks, Alaska, Tierra del Fuego, and the various points in between. And I had been waiting (I thought very patiently) through my twenties, through my thirties, through my forties, for them to finish that damn road across the rest of Panama like they had promised me back when I was a skinny little kid.

But at some point, as the old century faded away, and the new one still didn’t remotely feel like it was really starting, it finally sank in that they were never going to build any road across the rest of Panama. At least not in my lifetime. At least not while I could still drive a car unassisted.

And it wasn’t just due to intransigence or lack of will or even lack of money. Sure, the conclusion of the Panamerican might well have been finessed back in the Sixties or Seventies or even early Eighties. But now the political/military/drug situation was such that the last thing right thinking Panamanians could possibly want was a road connecting their country with Colombia.

Not only that, but it turned out that the last little uncompleted stretch was through an area called the Darien Gap. And this was one of the world’s most Godforsaken pieces of rotten swamp ever. So naturally all the environmentalists were dead set against messing with it.

Finally, there was the little matter of hoof and mouth disease. You remember that, don’t you? Probably not, since it had been eradicated in North and Central America back in 1929. But it still happened to be going strong in South America. So if you built a road connecting the two regions, then cattle would start meandering on up, and that would be that for our livestock industry.

So the road wasn’t going to happen. Not in my lifetime.

Not in my lifetime!…

Well, there’s a bit of a slap in the face from old man Mortality for you. Kind of puts the bookends around the idea of Adventure, doesn’t it? Turns out that there are just some things—hell, a huge incredible number of things—that you’re just going to have to leave this planet without having done. And one of these was that I was never going to be able to tell the story about how I got in my car in Nashville, Tennessee, and ended up in Puerto Natales, Chile.

Just wasn’t going to happen.

At least not in my lifetime.

Okay. I agree that it would be a pretty well spent life if not reaching Puerto Natales in the family sedan was your most important regret once you started contemplating how you’ve spent your allotted time. But it did rankle somewhat. Especially when I considered that other people—who had perhaps worked a little harder or perhaps been a little luckier—were now multimillionaires, and that for them there would still be no limitations of Time, no limitations on Adventure. They could afford to fly to Puerto Natales in their private jet if they wanted to. They could afford to be mushed across Alaska on the Iditerod trail if they wanted to. They could afford to buy a giant gold plated balloon and try to be the first person to go backwards around the world if they wanted to.

Well, what to do about this confluence of thoughts of mortality, feelings of failure, and downright pathetic envy?

How about: Run away?

Specifically: How about: Run away to the end of the road?

I mean: How about: Run away to the end of the road down in Panama?

The more I thought about it, the more sense it made. After all, there didn’t seem to be much heavy lifting involved, so it was something that a middle-aged guy like myself could probably attempt. Moreover, I didn’t have to be a multimillionaire: this was the sort of insane idea that just about anyone could afford.

And I’d like to see that Richard Branson guy trying to talk his way into Honduras with a faded registration slip and one year of high school Spanish!

Well, to be honest, it wasn’t like I was totally unprepared. I had driven extensively through Mexico four times previously. Twice I had even gone into Guatemala. I had once taken the bus across Central America from Panama to Honduras. I had been to Costa Rica two other times. And the Spanish I had picked up on these previous jaunts was sort of passable.

On the other hand, the last of those trips had been over thirteen years ago. In the meantime there had been any number of coups, wars, and insurrections. Not to mention various earthquakes and hurricanes. Plus all kinds of first and second hand reports of societal decay and vicious crime in the streets.

And the fact that I had crossed those borders before made me painfully aware of how intense and time consuming crossing borders in Central America can be. Especially with a car.

And—coming back and forth—there would be fourteen of them.

Oh, and then there was the car that I would be crossing those borders with. Or, should I say, van. As in VW van.

Although I hasten to add that it wasn’t a VW van as in the quaint underpowered counter cultural symbol of the Sixties. Nor was it a VW van as in the slightly more middle-class Vanagon of the Seventies and Eighties.

No, this was a Eurovan, a bigger and better version of the Vanagon, a van with big comfortable seats and a nicely torqued Audi engine and air conditioning and power windows.

No, this was a Eurovan, a bigger and better version of the Vanagon, a van with big comfortable seats and a nicely torqued Audi engine and air conditioning and power windows.

Problem was, although VW had gone to the trouble of making a bigger and better van, they had never gone to the trouble of actually trying to sell it. At least here in the States. They had attempted to, halfheartedly, for one year, in 1993, and then had given up. And now there were probably about 500 of them in all of North America. (And, as I was to find out, approximately zero of them in Central America.) Not to mention that I had about 140,000 miles on mine, and VW vans have never been especially known for their mechanical sturdiness.

Which meant that if anything happened—anything from busting an engine to busting an engine mount—I would be totally screwed.

On the other hand, I’ve always been aware that an adventure isn’t really an Adventure unless there’s the possibility that things can go wrong. And back to Richard Branson: I’m sure he’s a nice fellow and all, but why pose as an edge of your seat kind of guy when you and everybody else in the world knows that you’re a billionaire, and you can always pull out a checkbook and instantly rectify whatever trouble you’re in?

Anyway, the practical reality was that if it turned out that I was sitting around Guatemala waiting for a part to be flown in from Jacksonville, then it would really be no different—though a hell of a lot more exotic—than what would be the case if I broke down in Kansas City or Philadelphia.

So it was settled. Sort of. I would get my affairs in order, take six weeks off, and drive down to the Panama Canal and back.

On a wheel and a prayer.

As it were.

Not to mention one other thing that was going on. The recount to the 2000 election. It was going on and on and on. It had gotten way past the point of 24/7, and by now it was up to at least 38/10. And what made it more and more unbearable was my inner conviction that statistically freakish things like this don’t just happen. And if George Bush were to win then something would occur and that his particular incompetence would make it turn into something really, really awful. It was like I was waiting for God’s terrible judgment on us and our democracy.

I had to get out of town.

And thus, late on a Sunday morning, December 3, in the year 2000, with a light dusting of snow covering the bare, dead trees and gray, low-slung hills that surround Nashville, Tennessee, I eased out onto the Interstate that would carry me away and out into Texas.

I didn’t know if the snow was some kind of omen, since it usually only snows once or twice per winter in Nashville. But if an omen, at least it was one that was right purty.

Which was good, as there’s not much else on the drive through Arkansas and East Texas which inspires the spirit. Yes, there’s the giant pyramid/convention center and the Mississippi River at Memphis. Yes, there’s the giant Maybelline factory appropriately outside of Little Rock. Yes, there’s the excitement of driving under the overpass that separates Texarkana, Arkansas, from Texarkana, Texas. But we’ve all been on Interstates for forever now, and we all know that at this point just about everything unique or interesting or regional about the United States has been pretty much ground down to nothing.

So I made it to just this side of Dallas that night and found one of the many, many motels which were available.

And the next morning I got up, had breakfast at one of the many, many restaurants which unsurprisingly were also available, and headed on out across the barren Texas plains.

I planned to stop in Austin that afternoon, both because it was Austin, and because that was where I was cleverly going to start the process of getting into Mexico.

You see, it used to be that if you wanted to go into the interior of Mexico, you stopped at some little shack in the hot sun about twenty miles into the country, you filled out some simple paperwork, the fat Federale slapped a decal on your windshield, and you were good to go. But whereas the past decade had seen most of the rest of the world become less bureaucratic and annoying, the government of Mexico had decided to go the other way.

Now what you had to do was go through an incredibly confusing process of filling out complicated paperwork, not to mention actually being bonded, before you even got past the border.

But I knew from taking a short Mexican trip five years previously that if you were an AAA member, they would do all that stuff for you. And it certainly seemed worth the extra hassle of getting off the freeway and then finding the AAA office in the midst of the insane Austinian congestion.

For Austin was no longer the cute little laid back hippie college town that it had used to be. Now it was some suddenly overgrown high-tech mass of concrete with honking horns. And although the State of Texas was constantly building new highways, there were still far too few lanes for the vehicles that were attached to them to maneuver around in.

When I got to where the AAA office had been five years ago, it turned out that they had moved it to the other side of town. And when I finally found that strip mall, handed them my membership card, and asked them to fill out all the paperwork for me, I was met only with the dumb stares of young secretaries. At last one of the old timers from a corner desk piped up with, yes, they used to do that for members, but now Mexico had gotten even more bureaucratic and annoying. And I would have to do it all at the border.

But at least I could get my Mexican insurance.

For those of you unfamiliar with Mexican driving and insurance regulations, it works something like this: There is no law in Mexico that says that you must have car insurance. On the other hand, if you are in any kind of accident and you don’t have insurance, then you are thrown into jail until said accident is totally adjudicated. Which, it being Mexico, could take forever. And this applies even if you are totally blameless in said accident. Needless to say, most Americans, even usually relatively fearless ones such as myself, buy Mexican car insurance.

So I got my insurance and made my way back out to the Interstate that was already in progress and headed on down to San Anton’. Where, after my obligatory stop at the Alamo and my twenty minute stroll along the River Walk, I decided to have a last delicious meal of Mexican food before I crossed the border.

For I knew from previous experience that if you want great Mexican food, then many people like to go to Texas. Me, I prefer Southern California. But don’t ever, ever think that you’re going to get even decent Mexican food in Mexico. After all, the Mexican middle and upper classes like to eat steaks and sandwiches and Kellogg’s corn flakes, and what we call Mexican food is our gussied up version of what to them is poor people’s food. And poor people’s food, no matter where in the world it is, is almost always salty and greasy and nutrition less and all in all pretty damn wretched.

So I had the last half decent meal I was expecting to have for quite a while, and came outside to a dark, cold night and a freezing, biting wind. I noted that that wasn’t what I was expecting for south Texas, got into my Eurovan and started driving the last 150 miles to Laredo.

As I drove along I had time to think about the new, exciting, modern Mexico that all the news reports had been reporting on. After all, the new, exciting, modern President Vicente Fox had just been inaugurated a few days earlier. He was 6’6”, dynamic, a tough guy business executive. For the first time in over eighty years the government was no longer the moribund, dinosaurish, dictatorial PRI. Then there were all the high tech twenty first century high speed internet connections that Mexico was leaping forward to plug into. And not to mention NAFTA.

Indeed, NAFTA literally went right through Laredo. Or slightly around it. About ten miles before town there was an exit for the new international big rig cargo detour and bridge, and off in the dark distance I could see an endless unbroken line of semi headlights. And when I got to the city…

Right at the American side of the Mexican border, whether it was tiny Presidio, Texas, or giant El Paso, has always been an area of rather degraded 1940’s type 5 & 10 stores selling really cheap crap to Mexican nationals. The reason those nationals have always come across to buy it is because our cheap crap has always been better than the even worse crap they could get in Mexico.

So imagine my surprise when Laredo turned out to be a brand new, gigantic—and with plenty of free parking—expanse of representatives of every major American retail shopping experience imaginable. You might expect Walmart. But Bed, Bath & Beyond? Toys R Us? And acres and acres of mercury arc lamps lighting it all up?

Even the Motel 6 was brand spanking new. And $50 to boot. Plus I was about the only American staying there. So I supposed that, whatever else you might want to say about it, NAFTA was being pretty darn good for Laredo.

The next morning I got up, had breakfast at the IHOP next door, and then crossed over into Mexico.

Given the sparkle in Texas, I kind of expected the other side to be spiffed up, too. Not a chance. In fact, as I drove down the streets of Nuevo Laredo, I was almost shocked at how dirty and claptrap it all looked. And, yes, I am well aware that those ugly exterior walls can house beautiful interiors and courtyards, but that doesn’t help much when you are passing endless blocks of ugly exterior walls.

I finally got to the outskirts of town and found the giant new building where I was supposed to ‘temporarily import’ my vehicle. I parked and went inside.

I’ll try to keep this simple. There were about nine different offices or windows that one has to visit in a certain order. Except that there is absolutely no order to their layout. And when you’re done with one of them, the clerk may or may not tell you which and where the next one is. At the end of it all the fees are added up and you then go to the bank teller window to pay. Only then you go outside, where the not-so-fat Federale checks the engine ID, etc., etc., and finally slaps the sticker on the windshield.

All in all it took about two hours.

Now I was free to drive on to Monterrey, Mexico’s second biggest city, about fifty miles away. On the map I could see that a freeway led there. But I already knew that freeways in Mexico aren’t free, and that the government prices them in such a way that only the super rich can afford to use them. And I didn’t feel like paying $15 for fifty miles. So I took the old road.

That cold, biting wind in San Antonio had turned into a cold, steel rain. And in Mexico a cold, steel rain brings with it a cold, steel mud. And most of the traffic—and all of the trucks—was with me on the old road. So that by the time I got to the edge of Monterrey I could barely see out of a small portion of my windshield.

I had never before been to Monterrey, but I was looking forward to it. After all, it had always been described as the one city in Mexico with a forward looking, ’can do’ attitude, where people prided themselves on their competence. And maybe there are areas of town which are clean and neat.

But on the main drag that I came in on, on a cold, rainy, muddy, miserable traffic clogged Tuesday morning, it looked as ugly and depressing and backwards as any place can get. And, whereas in the rest of the Third World when you see a McDonald’s or suchlike they stand out as bright, cheerful, unsore thumbs, in Mexico these lonely outposts of the First World immediately become as drab as the rest of their surroundings.

The one exception to this was that every so often there was a Mexican version of a 7/11 store that actually did look like something post 1960. In awe and surprise I parked near one, went it, and warmed my psyche from the crisply uniformed clerk, the refrigerated sodas behind the glass doors, and the—gasp—fully functioning ATM machine.

Then it was back out into reality.

It was a long, long drive on congested surface streets until I got to the other side of town, and then there were about twenty miles of roadside businesses. (Yes, an inordinately large number of heavy, concrete lawn ornaments.) Finally, at around three in the afternoon the rain started to let up and I was in open country.

Now many people are petrified at the idea of driving in Mexico, and if I’m sitting in the States and haven’t done it for a while, then even I start to get a little fearful. But once you accept that there’s a different outlook involved (and also the fact that traffic laws are neither obeyed nor enforced), then in certain ways Mexican driving is a lot easier.

For instance, if you have to pass that belching truck that’s only doing 30, then the guy a few hundred yards ahead coming at you sees that and is quite prepared to slow down or even pull over (assuming that there’s a shoulder). Everyone involved is in on the dance.

(And if you think that this sounds too intense, reflect for a moment on how much more intense it is to drive in rush hour traffic on an eight lane freeway. You’re just used to that one.)

Anyway, right now driving was pretty easy, since northern Mexico, outside of Monterrey and the border area, is pretty empty (not to mention ugly) desert. And as the sun went down I was pretty close to my destination for the night, Ciudad Victoria.

I knew already that there was one half decent moderately priced place to stay at in town, and I found it easily enough. But when I went to the front desk they wanted $50 a night. $50 a night? In Mexico? I’m sorry, maybe I’m too old school, but no place in Mexico should charge more than $20 a night. I looked on the map and saw that there was a town, Tlachiploticatlan, about fifty miles further on. I decided to go there.

Now even the guidebooks that tell you that it’s perfectly all right to drive in Mexico go on to warn you to never, ever even think of driving there at night. You know, burros on the road. Unseen potholes. Cars with no headlights.

But somehow I always find myself doing it. For hours and hours. Right now it was because even though Tlachiploticatlam was only fifty miles away, it was fifty miles of tiny twisting mountain roads.

Not only that, but now that I was in the mountains I was in indigenous territory. And then when I finally reached the town around ten thirty I found out that tomorrow was market day. Which meant that all the hotels were totally full up.

Needless to say, I was getting a little tired and grumpy. But I had no choice but to get back in the van and continue driving.

Which I did for about twenty more twisting miles. Then I gave up, found a little ledge off to the side, parked for the night, and crawled into my bed in the back.

Now I know that most people would probably totally freak at the idea of sleeping in your van by the side of the road in Mexico. But here, once again, they’d be wrong. Because for all the talk about banditos and kidnapping and such (and they’ve been talking about those things forever), Mexico is a much kinder, gentler, safer place than the U. S. of A. Really. Especially out in the middle of nowhere. Especially out in indigenous country.

So I slept. Soundly.

The next morning I awoke, and when I looked out my window there were three colorfully dressed short people carrying large bags of oranges up the hill. Around me were wild palms and other lush tropical foliage. I climbed in the driver’s seat and continued on my way up the hill.

And up and up and up I went.

The reason I had chosen this particular route was that in 1975 I had come down the same way in my 1968 Dodge van, and the views out over everything had been breathtaking. What I had now failed to take into account, though, was that going up generally means that all you tend to see is the diesel exhaust of that truck in front of you.

And twenty five years later Mexico had not done one single iota of a thing to improve the damn road. It was still two twisting, turning lanes—with no shoulders whatsoever—that ever so slowly, for about 150 miles, snaked up the mountain. There was one medium sized town about halfway up, and if you ever wanted to pull over, that was about it.

This gave me plenty of opportunity to re-connect with the art of passing on a blind curve. Because with some trucks never making it past 20 mph, at some point it’s making you so crazy that you’d rather just take your chances and die. And, actually, if the truck’s only doing 20, it doesn’t take too much space or time to do it. It’s when they’re doing 30 or 40 when it starts getting tricky. Then you have to mentally calculate the odds of an approaching vehicle occupying the exact same space at the exact same time and weigh that against how incredibly frustrating it feels to be here now. The fact that I’m here writing this means that up until now I’ve always guessed right.

And on this day I was feeling conservative and slow, so I kept the putting my life on the line to the minimum. And what with all this extra time I had the opportunity to re-acquaint myself with the absolutely most annoying thing about driving in Mexico: Topes.

To explain topes one first has to explain something about the Mexican government psyche. And to do that one needs to explain a little something about the Spanish Catholic church.

To wit: In most religious and philosophical traditions, the sophisticated viewpoint is that Sin is a result of ignorance and foolishness. In this viewpoint, the evolved soul immediately grasps that Virtue is its own reward, and changes its behavior appropriately. This, however, was not the case in Spain, which had always been the most backward region in Europe. To the Spanish Church, Sin was actually horribly wonderful, exhilarating fun. It was so much fun, in fact, that even priests wanted to do it. Problem was, Sin was also synonymous with eternal damnation. And this meant that the Church had to constantly and mercilessly beat the impossible-to-evolve donkeys of Its flock.

Move the concept over to Mexico, where there were many, many more actual donkeys, and change the idea of Sin to that of Speeding, and you’ll start to understand the insane fixation with topes.

For topes–sometimes also called rumbles or (the appropriate) vibradores–are speed bumps. And not just shopping center type speed bumps, but giant chassis-destroying-if -you-go-over-3-mph versions of same. And there are at least three sets of them before you hit the smallest village, and at least 3 sets as you leave said village. Sometimes they’re just in the middle of nowhere for no reason at all.

And sometimes there are signs for them, but usually there aren’t. And sometimes if there are signs it turns out that there aren’t any. And the worst part is when, after you’ve past the third set leaving the small village and have sped up to, say, 40, there’s another unmarked set.

Like I said, I had plenty of time to get used to all this. Finally, at around three, I made it to the top of the hill. I was now at around 7000 feet, which is where most of central Mexico exists. Mexico City was about 70 miles away.

There were now more than two lanes. But there were now also infinitely more diesel spewing trucks and buses. And I was surrounded by the sort of industrial detritus that only a Third World country can provide. I pulled over at a Pemex station to carefully study my map.

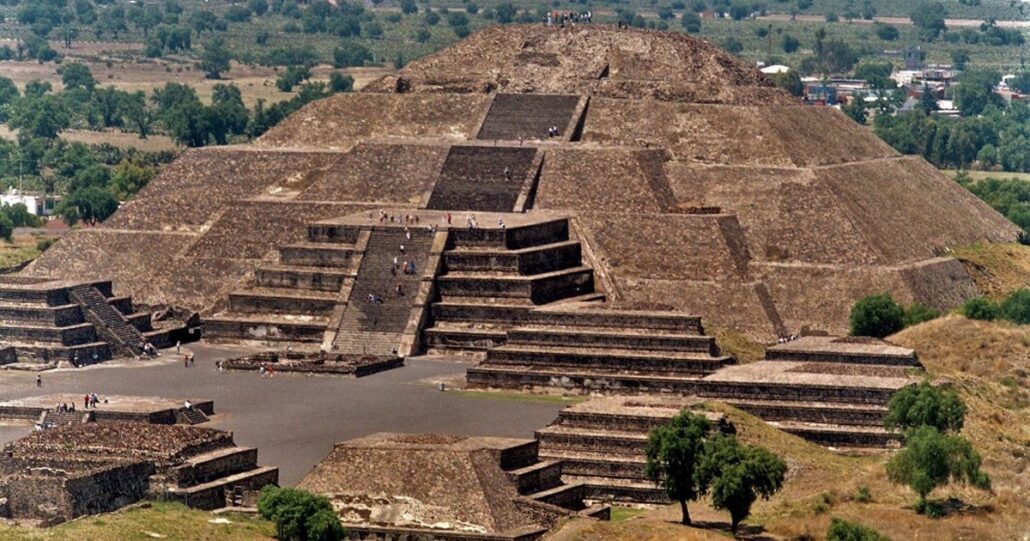

Because I wanted to make it to the pyramids at Teohtuican before they closed. And Teohtuican is slightly northeast of Mexico City, but right now I was slightly northwest of Mexico City, and the last thing I wanted to do was to have to drive through Mexico City.

Because forget what I said about Mexico being so easy to drive through, since this does not even remotely apply to the capital. Of course, they still have the ‘no rules’ approach of the rest of the country. But they also have an endless confused mess of hopelessly overcrowded eight lane freeways. You miss your exit, that’s it. You have brought Damnation upon yourself. Because there’s no way of ever finding your way back.

Indeed, if you enter the metro area on a toll road, as you pay the toll, standing around will be some guy that you can hire who hops in your car and then directs all of your turns so that you end up where you had wanted to be on the other side of it all. He then smiles, shakes your hand, and gets out and waits for his next customer.

But, as stated, today I had zero desire to go to or through the monstrosity of Mexico City. And according to the map, if I went there, and then there, there was this little side road that led directly to the pyramids. Fortified and prepared, and also full of gasoline, I started out.

Well, this wasn’t the first time that I had tried to find that road, and it wasn’t the first time I failed. But you’ll be happy to know that if you circle around, get on the main North/South tollway, and then be sure to be in the left lane at the proper time and do a U-turn to the special Pyramides toll way, you get to bypass most of the megalopolis.

The pyramid complex at Teohtuican really is one of those sights that you need to see. Not quite as overpowering as the Pyramids in Egypt, but still pretty neat. And, due to recently enforced laws by the Mexican government, there were far fewer people than there used to be following you around the site constantly pestering you to buy an onyx chess set or some suchlike from them.

In 1980 I had arrived just before closing, and even though I wasn’t in particularly good shape I had jogged up the steps of the main Pyramid of the Sun. Then I had danced around Rocky-like as the sun went down. Twenty years later I had several more hours available, and, boy, did I need it, creaking knees and all. When I finally completed my ascent, however, the view was once again worth it.

Down below to my right stretched the ‘avenue’, lined on both sides by lesser pyramids. At the far end of it all was the Pyramid of the Moon, which was slightly less grand than the one I was standing on. And, while I was taking it all in, not to mention catching my breath, I was free to contemplate the Mysteries of these pyramids.

First was the question of who actually built them. Archeologists say it was the Toltecs, but that’s because the Toltecs are the only culture we know of which could conceivably have constructed them. For all we know, however, they—like the Aztecs did centuries after them—simply came upon the pre-built complex and appropriated it.

For me the more interesting question was: Why the hell build it all the way out here in the middle of nowhere? Seriously, as you look around you can tell that this is one of the most desolate areas imaginable, and that’s saying a lot for Mexico. Even with the possibility of modern irrigation, etc., there’s nothing to the horizon. Cacti don’t even grow.

Well, after a while my mind tired of such deep thoughts, so I creaked back down all the stone steps, took a stroll up the avenue, and then made the obligatory climb to the top of the Pyramid of the Moon. Then, appropriately, the moon had come out. And the sun was sinking slowly in the overwhelming Mexico City smog. It was time to leave.

I was still trying to circle myself around the whole mess, and in this I was pretty successful. For most of it I even had the luxury of multi-lanes, although by no means does that mean an expressway. At one point, typically, even though they had built a pedestrian overpass and had constructed fences all along the road so that no one could possibly get on it, there were still bone and van jarring topes.

Unannounced, of course.

By eight o’clock I had made it to the Puebla toll road and was sitting at a Mexican truck stop eating some bad enchiladas and beans and intimately suffused with even more diesel fumes. Once again I was pondering my map.

The planned destination was Oaxaca, that quaint and storied Mexican jewel of the south. I had actually done the same route back in 1980, and my memory of the long and tortuous unending drive there made me glad that they had recently completed a toll road. For this leg of the journey no price could be too high.

So by ten thirty I was cruising along doing 70 in the moonlit, otherwise dark, dark night. Okay, time to find a place to pull over and sleep. Up ahead there was a little quarry-like area which blocked the view from the road. Perfect. I pulled over, changed into my pj’s, and conked out.

A couple of hours later I was awoken by a tapping on my back window. I opened my eyes and found myself staring at the barrel of an automatic weapon.

Not to worry. Said weapon was dangling from the shoulder of a friendly policeman. And this is another myth: That one needs to be very afraid of Mexican police. Maybe if you’re a Mexican. But I’ve always found them to be super proud in being completely civilized and correct to visiting Norteamericanos.

And when I stumbled myself together and opened the door he was exceedingly polite for two in the morning. But could I please be aware that it was against the law to sleep on the side of Mexican toll roads? On the other hand, there was a well lit service area just 15 kilometers on further, and he was sure that they wouldn’t mind one bit if I spent the night.. Or, if that was unsuitable, once I had exited a Mexican toll road…

I thanked him, got in the front seat, and drove off. The service area did turn out to be a little too well lit for my taste, so I took the next available exit, found a nice secluded spot in the middle of the dry mountainous wilderness, and hunkered down again.

Right at dawn I was jolted awake by what sounded like the thunderous clap of artillery being fired from every direction. Okay, what had I driven into the middle of now? When I sat up and gazed through the twilight’s first gleaming all I could see was what looked like a tiny settlement several miles away. As it slowly dawned on me that what I was actually hearing was non stop monster firecrackers, I lay back down and tried to figure out why in the world people would be doing that at six in the morning. Let’s see, what’s today? December 7. That’s not a holiday anywhere, is it? I got out my tour book. Oops, yes it is. In fact, it’s the Our Lady of Guadaloupe holiday, the one that celebrates Mexico’s patron saint. I was now mostly sure that nobody was coming after me specifically, so I lay back down to get some more shuteye.

That proved to be a fruitless endeavor, however. So after a while I got up, put on my real clothes, and went out for my morning constitutional.

People think of our saguaro cactus as the towering grand symbol of the American Southwest. What they don’t realize is that right across the border insanely large cacti—some forty or sixty feet tall, with whole forests of them covering entire mountains—seem to dominate half the Mexican countryside. Okay, maybe not half. But, geez, it’s a barren land.

And the state of Oaxaca hadn’t lost out in the barrenness sweepstakes. As I revved up the ol’ Eurovan and got back on the tollway I noted once again what I had noted many times before: Poor and backward are intimately connected to bad soil. The dry brown hills and mountains around me were picturesque as hell, but they didn’t put any food on the plates of the local inhabitants.

Speaking of which, where were those colorfully dressed folks? I guessed that I was witnessing another instance of the Tragedy of the Interstates, since the only signs of civilization that I was passing were Pemex stations and new-but-immediately-old tire repair places.

But then I did see some people. About twenty teenagers, some of them barefoot, running along the side of the road. With nowhere to be running from or to. And they seemed to have a slightly older group leader. This was odd.

And about fifteen miles later there was another group. All barefoot. And the pavement was already super hot. This time the lead runner was carrying a cross.

The third group was a few miles further and it was running in the opposite direction. And I could see that this lead runner was holding aloft a crude tapestry of the Virgin of Guadeloupe. Now it made sense.

No, not really. What possible connection could there be between Guadeloupe Day and thousands of teenagers in Mexico torturing themselves in the brutal hot sun? Were the various congregations competing with each other? Were they raising money for charity? Why be running from nowhere to nowhere? This seemed to be out of some existentialist Beckett play, not religious faith. I mean, if they had been forced to do this, it would be a war crime.

Still, the groups kept appearing and disappearing. Crazy country. And that reminded me, where were all those modern 21st century computer loving Mexicans that I had read so much about? So far I had driven well over 1000 miles into the country, and I still hadn’t seen one person who wasn’t dressed in the same shabby way that Mexicans had dressed in 20 years earlier. I still hadn’t seen one city or part of a city that wasn’t as shabby as it had been 20 years earlier.

In fact, as I finally pulled into Oaxaca I realized that things actually seemed shabbier now. In 1980 I had started my morning at the ruins of Monte Alban (although once you’re used to giant Mayan pyramids and giant Toltec pyramids, a few building foundations and archaeological scratchings aren’t that impressive). Back then by one in the afternoon I had made my way to the zocalo (main central square), where a sunburned British film crew was shooting a movie about D. H. Lawrence in Oaxaca in the 1920s. And that afternoon as the market was about to close I was haggling with the ladies over how much to pay for my pile of huaraches for me and shawls and peasant blouses and hippie skirts for the women back home.

Now, as I parked and started to walk around, it was… shabby. The zocalo lacked zing. When I went into the cathedral it was filled with scaffolding and noisy workmen drinking beer and eating lunch. Yes, there were some college age ‘backpackers‘, but they looked lost and listless. And there was even an expat of around 65 with a trim white beard and a broad rimmed hat who looked like he imagined himself to be D. H. Lawrence. But this was the year 2000 and he was walking past hole in the wall internet places.

As for those great embroidered Mexican crafts of yore, nobody sold them any more. Because none of the tourists or visitors bought them any more. Perhaps if the artisans had been clever enough to stick designer logos on their skirts…

I was wandering around a few blocks from the zocalo when I happened to pass by a Mexican health food store. A Mexican health food store? I had to check that out.

It was mostly earnest and quaint, kind of like a health food store in the States would have been in the 1950s. Although this place had lots and lots of cans of Mexican made soya ‘meat’. But what caught my eye was a poster up by the cash register. On it was a 30ish Mexican guy in a 20,000 peso suit and a 2000 peso haircut. He was coming to town to lecture in a few days, and the caption read: “I just can’t WAIT for all the excitement and opportunities that this new Millennium will be bringing!”

Okay, if overpaid and over pampered Americans want to waste their money on New Age claptrap, that’s up to them. But it seemed something between laughable and criminal for somebody to be going around Mexico conning the poor citizens into thinking that they, too, could Be Whatever They Wanted To Be. I mean, look around you, people. Don’t you get it? EVERYTHING IS JUST TOO FRIGGIN’ SHABBY!

I bought a few items from the store, found my parked vehicle, and headed out of town.

The expressway was of course long gone by now, and I was back on the two lane road that snaked down, down, down the horrible thicket of mountains that Oaxaca is in the middle of. Once you get re-acclimated to re-shifting gears every fifteen seconds it’s kind of fun. And, all kidding aside, I wouldn’t have returned to Mexico unless I really enjoyed it and its poor beleaguered people.

Indeed, as I reached the bottom of the mountains around dusk I stopped for a moment at a small town slightly misty in the tropical heat. All around the square sauntered young and voluptuous women, some with babies, some still single. Fortunately none of their not-so-young-or-voluptuous older sisters and mothers were there to destroy the illusion.

Not to worry. As soon as darkness descended (which it does mighty fast in the tropics) and I was on the main road, all illusions, not to mention faith and hope, were shattered. For I was on the Isthmus of Tuantepac, the narrowest part of Mexico. It is flat and hot and lifeless, and was considered hell long before they put in all the industrial slagheaps that stretch to the horizon.

And then there was the traffic. Endless, countless fallen down diesel rigs crowding each other every which way. At least when you are in hell you can think back on all the fun of the Sin that got you there.

It was getting too intense for me, and generally speaking that‘s saying a lot. What, was it only two and a half days ago that I was having breakfast at the IHOP? I desperately needed a bed.

As you might or might not imagine, there aren’t too many motels in Mexico. And when they do exist it’s primarily for, shall we say, romantic trysts. The one I found was a dirty mess behind a Bosch-esque truck stop. If I were the cheapest of clichéd Mexican whores I wouldn’t take my customers there. But the price, $8, was right, the shower seemed to work, and there was a fence around it all so that my Eurovan would be safe.

I spent the night.

The morning’s early light didn’t make the highway scene very much less ugly. Fortunately, though, I was soon heading back up into the hills, this time the hills of Chiapas, Mexico’s southernmost state.

First I passed the moderately large, moderately industrial city of Tuxtla Guiterrez. I noted both the new Walmart and the fact that the new Walmart already looked drab. Then it was up and up until finally it was almost real mountains again. This time, however, they were very pleasantly forested.

Chiapas is also Mexico’s poorest state, and—not coincidentally—its most indigenous. But this is not because its inhabitants were of the proudest or most resistant tribes. Nor that somehow they are being persecuted or exploited for being indigenous. It actually works the other way around: Generally speaking, peoples who are still indigenous are those people who had just happened to be living in those areas which were of no economic use to ‘civilized’ folks. Otherwise, the economic forces would have rolled in long ago, they would have gotten jobs in the factories and mills, and by now would have all been folded in with the rest of us.

I’m not saying that I think that this would have been a good or bad idea had it happened. And it’s hard to hang around indigenous people anywhere and not feel a lot of sympathy for their plight. In 1980, for instance, I was in San Cristobal, the capital of the highlands, on the weekend that they had their annual spring fair, with people selling cotton candy and blown glass figurines and commemorative Pepsi bottles. And someone had put up a portable bumper cart ring in the center of the square. Sunday morning all the little fat kids from town in their white shirts got to ride around in the bumper cars for ten cents a go. And the Indians were there too, children and adults in their Sunday finest. But all they could do was stare longingly through the mesh cage at the privileged elite who were enjoying something that they could never ever hope to attain.

I was soon pulling into San Cristobal again, and this time for once I had to hand it to Mexico. Or at least to the city of San Cristobal. This place was spiffed up, with the freshly painted white colonial structures, the cobblestone streets. Here was someplace that a tourist might even want to stop.

And when I did stop and start to walk around, I noticed something else. This was the first place in Mexico that had an ‘international’ feel to it. By that I mean cappuchinos, quiet restaurants that serve healthy sandwiches, gift and clothing stores that are at least three levels above tacky. I mean that some of the restaurant owners, or dare I say even art gallery owners, are French or German or Italian. Mostly, though, ‘international’ means that it didn’t have the stale, worn out vibe of Mexico permeating it.

A delightful excuse to slow down for a bit. A delightful excuse to stay for a while.

But by late afternoon I had had about as many delicious coffees as I could handle, so I started out again. This time due north.

And found myself at twilight at Las Cascadas Azul, the Blue Pools. In fact, I had just paid the entrance fee for an official Mexican ‘State Park’ type campground. Complete with tent space and picnic table. You don’t see too many of them around these parts.

And there were even actual middle class Mexican campers there for the weekend. Granted, they were mostly college students from Mexico City, so that this part of the country was probably much more foreign to them than it was to me. But they built a campfire and sat around it playing guitars and singing songs, and we all had a wonderful time.

When I walked around in the morning, I noted that most U.S. State Park campgrounds probably don’t have signs that read, ‘Please don’t walk on any of the forest trails. Women have been raped and killed there.’ But so long as one stuck to the pools and the cascades that connected them, it was all quite natural and lovely.

But this wasn’t my primary pursuit of the day, so after a bit I hit the road. Within about an hour I was at the Palenque parking lot.

I first saw the Palenque ruins in 1980, and they are another of those wonders that you look forward to seeing that don’t disappoint. Back then the parking lot was gravel, you paid $2 to get in, and there were workmen in the hot sun constantly hacking away with machetes trying to keep the sedge grass and the rest of the jungle from taking over.

For Palenque is the only one of the major Mayan ruins which really fits the fantasy: Sticky and humid, set within bumpy hills covered with vine infested forests impossible to penetrate. One feels like a little kid climbing up the narrow and steep terraced steps to the top of each ‘building’, then descending into the dank ‘rooms’ in their depths.

Back then, after a bit of exploring, I had noticed a backpacker type sitting on one of the walls with a big grin on his face. I walked up to him and asked him if he was an American.

‘Yes, I am,’ he said.

‘I thought so,’ I replied. ‘You see, I have this theory that, contrary to popular myth, Americans are a lot happier, and a lot more open, than Europeans or other foreigners.’

He said, ‘I don’t know if you’re theory is correct or not. But the reason I’m smiling right now is that I just ate a whole bunch of mushrooms.’

It seems that the little kids in the area would go out in the nearby fields in the morning and collect magic mushrooms. Then they would go around to the backpacker hostels in the area and sell them fresh off the farm. In fact, my new friend had a bunch left over, so he gave me some.

In less than an hour I was experiencing Palenque in a whole new way. For it was interesting enough when you were at the edge of the dank jungle exploring ancient Mayan ruins. But when your fingertips are way out there at the ends of your arms, and your feet aren’t even connected to your body any more, well, it does add a certain, uh, vibrancy.

(Not that it made me appreciate the Mayans any better. No, if you study their history and culture without PC glasses on, you’ll find it to be as creepy and mega violent as you can get. I mean, I’m sorry, but cutting the hearts out of the losing ball team is just a little too over the line for me. And to think that they were probably doing that after ingesting those magic mushrooms…)

Anyway, on that day I left as the sun was melting into the west and a mist was hovering over those same fields. And as I drove along in twilight, right next to me a giant owl flapped along beside me for about three hundred yards.

Back to the present. The parking lot was now paved and it was filled to overflowing with tour buses. It cost a lot more to get in. And instead of little boys with plastic bags of brown psychedelia there were well ordered gift shops.

Once inside, the guys with machetes had been replaced by guys on riding mowers. And all those tour buses had disgorged a lot more people on to the site than there had been previously.

But all in all the ruins were as spectacular as ever.

After a couple of hours of walking up steps and down steps in the hot sun, though, I realized that I hadn’t eaten yet today. So I went back to the parking lot and drove the ten miles or so to the town of Palenque.

This town has a very slight tourist aspect, but mostly it’s a dusty, drab, slightly less than midsized poor Mexican town in the boondocks. I found a dusty, drab restaurant, and ordered myself some dusty, drab Mexican food.

As I was sitting there on this Saturday afternoon drinking a Mexican refresco and stuffing bad tortillas, rice, and beans into my face, I noticed what was on the TV: Mexican Teen Dance Party. Different cities from across Mexico were beaming in with their particular parties, and all the teen girls were dressed to the teen hilt and babbling about their fave Mexican teen idols and waving and screeching to their BFF’s in Merida or Zacatecas.

I looked around me at all the dusty, drab Mexicans sharing the restaurant with me. Was I the only one seeing the horrible disconnect here? I mean, I could see in theory that there might well be a colony of International Modern Mexicans living somewhere in Mexico City. But Merida? Zacatecas? Give me a break.

A few hours later it was dark and flat and really windy and I was driving alongside fields of tall grass. I could tell that that’s what it was because several of them were burning furiously. Then I had to slow down a bit because there were about twenty young people along the side of the road. Still running for Guadeloupe! And several of them were carrying torches on this really windy night. Now I would have liked to think that those burning fields had been deliberately set by farmers for some reason. But…

Anyway, a few hours later it was still dark and flat, although now I was halfway across the southern Yucatan and approaching the semi-major town of Ixtlan. I was really hoping by now for a half decent hotel of some kind, and, yes!, there it was. I gladly paid them whatever they asked, and then waited while they guided my van into their tiny enclosed parking area.

As I was relaxing on my bed a half hour later I heard them guiding something much bigger in. And then I heard—Did I really?—the distinctive twang of Tennessee. I went out to see what was happening.

And there I met Whitey. In his seventies. From Sevierville, TN. That’s in the Smokies, right next to Pigeon Forge and Dollywood. A couple of years earlier Whitey had decided to move to San Ignacio, Belize, put up a Quonset hut, and open a store. He had done pretty well by it. So he had just driven his large pickup truck pulling his large empty trailer back up to Tennessee, and loaded them to the hilt with more stuff. Now he was on his way back. Along with his younger, silent, faithful black Belizean friend.

I was more than impressed with Whitey’s pluck, drive, and creative thinking. Talk about thinking outside the box: Who in the world in this day and age would conceive of a Quonset hut? We talked for a bit about Tennessee, and then I went off to bed.

At three in the morning I was re-acquainted with yet another of Mexico’s peculiar phenomena. In just about every mid to large sized town in the country, in the middle of an otherwise perfectly still and quiet night, somebody somewhere will start playing incredibly loud Mexican music through incredibly large speakers. Then there is never any sound of people shouting out to Shut The Hell Up, nor of trucks driving over there, nor of shots being fired at either the perpetrators or their incredibly large speakers. And after about forty five minutes of soul wrenching noise, the music suddenly stops, and the night goes back to being perfectly still and quiet.

I lay there in bed staring at the ceiling and trying to contemplate the insanity of a society that allows this. Especially considering that everybody in a town this size pretty much knows everyone else. Then at 3:45 it all got silent again, and I went back to sleep.

Sunday morning I was driving east across the rest of the Yucatan. For you who only know of getting a tan at Cancun or Isla Mujeras, you may not be aware that the interior of the place is hot, totally flat, dull white limestone covered with scrubby yuc. And Chetumal, the small city at its southeastern edge, and the capital of the strangely named state of Quintana Roo, while exuding a certain frontier charm, sure ain’t no resort.

Around eleven thirty I was about five miles east of there, heading for the border with Belize. I had been through here in 1980, so I already knew that this border crossing got maybe ten vehicles a day. So imagine my surprise when I found myself at the tail end of a line several hundred cars long.

This was hard to believe. It would also be impossible to wait that long, considering how long it takes to do the cross border paperwork. I eased myself out of the line and proceeded on up to the front.

There it all made sense. Because in the intervening years Belize had opened a Duty Free Zone, basically an acre or two of barbed wire fenced BIG DISCOUNT PRICING! Or, as they were nice enough to translate for their Mexican customers, MAS MEJOR PRECIOS BAJOS! And it was Sunday, shopping day. And apparently even Belizean crap was better than Mexican crap. I cut across the line again and went over to where I could begin the process of taking me and my van out of Mexico and into Belize itself.

About an hour and a half later I was in the northern Belizean town of Coronal. Whoa, what a difference. First, everyone was civilized enough to speak English. Second, the pace was way, way slower. Almost to the point of non-existence. Third, what the hell was a Bank of Nova Scotia doing on the corner?

Okay, I already knew about that, having previously been here. Canadian banks pretty much own most of the Caribbean region. And that was the crucial difference with Mexico: Even though there were a smattering of Mexicans here, along with Mayans, Chinese, and even the occasional Mennonite in old world garb, most of the people in Belize were Caribbean Blacks. And this was the vibe—changed slightly since this wasn’t, after all, an island—that dominated.

You also had to factor in Aldous Huxley’s famous remark that if the world had any ends, then Belize (at that time British Honduras) would be one of them. Because although in the past twenty years Belize had become an oh-so-precious yuppie vacation spot, all those people were frolicking out at the exclusive and private resorts about twenty miles offshore on the cays that dotted the world’s second longest coral reef. Virtually none of that had penetrated mainland Belize, and it was still about as poor and backward and motionless as you could get.

Back in 1980, once I had gotten past the slightly settled north there was about a hundred mile stretch of road that was literally one paved lane through the jungle. No shoulders. Virtually no turnouts. And dark overreaching forest the entire time. It was actually an incredibly enjoyable drive. Although it did get interesting the few times there was oncoming traffic.

The New Millennium, however, had brought with it a new two lane highway, complete with shoulders, that now skirted the jungle area. And this is what I glided into the outskirts of Belize City on. There was the new airport. Now a few modern government buildings. And soon downtown.

Well, at least they had paved the main street. Before it was mud. And some effort had been made to prop things up. But not much. Belize City was still the place that really put the shack into ramshackle.

During the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, the correspondents on the ground kept saying that it was impossible to convey the stench, the filth, and the ugliness of it all. From my world travels I knew what they meant. You see something that is so degraded and sad and awful, and you say to yourself, I’ve got to take a picture of this to show people back home. And then the picture turns out to be somehow kind of bright and sparkly. With video it’s triple that.

Anyhow, that’s kind of how it is with Belize City. It’s hot and humid. It smells. The paint on the wooden houses is chipped and fading. They seem to have no interior framing. The stilts that they are on are invariably sagging. And what makes it most disturbing to an Anglo-Saxon is that they all started out being quasi-replications of Victorian buildings.

On top of all that, it was now two weeks before Christmas, and so there were little cardboard Santas and other ersatz decorations hanging in the putrid air.

The entire population of the country is only around 100,000, so one wouldn’t expect grand monuments and expansive parks here in the capital. But, still, as I drove around I was reminded of how ridiculous it all was. I would pass a completely broken down wooden building with a weed choked overgrown lawn, and there would be a sign saying ‘Ministry of Justice’. The Belize River was still a dark, slimy cesspool. The only open grassy area was less than an acre, and it was here where Belizean women set up a little farmer’s market every day.

Moreover, this was still the sort of place where you could get knifed on Main Street. Which meant that this wasn’t the sort of place where one wanted to park one’s car and walk away more than twenty feet. So after driving up and down and up and down all the little side streets, and marveling over and over again at the beyond world class funkiness of it all, it was time to head west into the interior.

Technically Belize City was no longer the capital. About twenty five years earlier that had been moved to the ‘planned city’ of Belmopan, about fifty miles inland. This hadn’t really worked. In the year 2000 I could see that the place was still an awful little hole in the wall with a few open air food stall/restaurants and a rundown bus station/piece of mud. I continued on to San Ignacio, the only other town on this road.

I reached it at twilight, and could see that it was a reasonably nice (for Belize) place of a few thousand nestled in nicely rolling jungle hills. I even saw Whitey’s Quonset hut a few blocks over. But when I pulled up it was closed for the evening. Oh well. I continued on to about five miles further, where there was a well regarded private campground, complete with hot showers and mown lawns and beautiful shade trees and everything, run by a nice Spanish speaking lady.

After all, we were almost at the Guatemalan border, and now the Caribbean and the English language and all of that were firmly in the rear view mirror.

For almost all of their mutual existence, Guatemala has claimed Belizean territory as its own. But since Britain had been behind the whole British Honduras enterprise, the Guatemalans were never able to do much about their claims. On the other hand, they sure as hell weren’t going to build any kind of road connecting the two places. This meant that up until about a year ago there had only been a storied bone-crushing 10-mph-if-you’re-lucky track once you crossed the border.

In the spirit of international brotherhood, however (plus undoubted international arm twisting), Guatemala had recently started righting its wrongs. Its customs and immigration station was a model of friendliness and efficiency, and I was out of one country and into another in only 40 minutes and for only $14. This would turn out to be a record for my trip.

And once I was through to the other side, not only was the road straightened, widened, and graveled, but most of it was now paved. It was thus an easy and quiet drive through the forest for an hour and a half. Then a right turn, and some more easy driving for another 30 miles. And then I was at the entrance to Tikal.

Here was one of the few places in North America that I had always dreamed about seeing but still hadn’t gotten to. Here was the granddaddy of all Mayan ruins, countless pyramids stretching out in mind numbing grandeur, stuck out in steaming hot swampy jungle that even Indiana Jones would be scared of entering. Where death by caiman chomping would be far preferable to the slow agony of having your blood sucked out of you by the countless swarms of mosquitoes constantly hovering around you. This was the ultimate Mesoamerican nightmare, yet also the ultimate Mesoamerican adventure.

You’re probably guessing where this is going.

For I paid my entrance fee and started walking on the path through the forest. That’s right, forest. Not jungle. No vines, no undergrowth, nothing remotely as fecund as, say, the Southern woods in summer. And this was supposed to be the rainy season, yet there was no mud or rivulets of water anywhere. True, there were some awfully damn cute coatamundis—Central America’s ecological substitute for raccoons—sniffing around with their comical conical snouts, but they just underscored the fact that there was absolutely nothing even remotely threatening or otherworldly about the place. What’s more, the topography around here wasn’t even all that flat.

And then there’s the matter of the Mayan structures. After all, when you go to the pyramids in Egypt, you just can’t get over how (not to mention why) they got all those incredibly huge slabs of rock in place. (And, yes, I’ve read all about the theorized inclined ramps and pulleys and all, but I’m still betting that they used cosmic anti-gravity devices.) The ones I had just seen again at Teohtuican weren’t quite as amazing, but still pretty darn impressive. And down in Peru, the Inca walls in Cuzco have a precision in their construction that might even top them all.

But all the Mayans did was basically glue countless thousands of pebbles together with some sort of concrete, and then just put smaller layers on top of the last one. Over and over and over again. As far as I could tell a twelve year old (albeit with unlimited powers of command) could have engineered these ‘pyramids’.

And then there was the problem of boring repetition. Because it was kind of fun to walk all the way up to the top of the first big one and look out over the forest. But once you’ve done that all there was to do was to walk down, over to the next one, and then up again and look over the same forest. Then down and up and down again. Then you would walk for a quarter of a mile to the next collection, and repeat. True, there were stone sculptures and hidden rooms and all, and the guide book would go on and on about the significance of it all. But I had just seen the exact same colored stonework and the exact same sorts of sculptures and hidden rooms at Palenque. And also, by the way, at every other Mayan site I had ever seen. And unless you’re a post doctoral student in archaeology it seems like it would be hard to get worked up in the hot sun over whether this or that had been done by the Fifth Dynasty in 1020 or by the Seventh Dynasty in 1165.

Because here was another problem. King A would build a temple 115 feet high. Then fourteen years later, King B would build a temple right next to it 122 feet high. Most of Tikal therefore was simply a monument to one-upmanship by egomaniacs who got off on cutting the hearts out of the losing ball teams.

Okay, if you go to Tikal you might have a different reaction. But this was mine. So as I left the parking lot and drove on down the road I set my sights on the next cherished fantasy, the town of Flores. The remote capital of Guatemala’s vast low lying Peten region, this place was built on an island in the middle of a beautiful lake, connected to the mainland by a long, thin causeway. Surely this couldn’t disappoint.

Guess what? It could. Because on the mainland where the causeway started there was just an endless strip of grubby bus stations and gas stations and the like. And then once you got over to the town it was just a crowded, larger version of what you had just left. I went down to the lakefront to see the sunset, and there was all kinds of garbage floating around.

I went back over the causeway and filled up at one of the gas stations. Then it was fifty miles or so further into the darkness and the middle of freaking jungle nowhere. I was headed for the legendary campground at Finca Isabel.

This wasn’t primarily a campground, as I confirmed once I had arrived. Most of the dozens of people there were backpackers, and most of them seemed to be under 25. Not that there’s anything wrong with that, of course. It was just weird, this being—did I mention?—the middle of freaking jungle nowhere, and considering Guatemala’s recent history, to see so many (to me) clueless cherubs both here and alive. It also seemed a testament to the unseen Isabel that she built it and they did indeed come.

I was glad I came, too, because dinner was a delicious health food vegetarian buffet prepared by eager latter day kids dreaming of being hippies. And after dinner I went outside and walked around the finca (Central American for small farm). There were showers, a little outdoor swimming area, horses for them to ride in the morning. Moreover, the whole area was fenced, so that no wild animals or Guatemalans could come in and attack them at night.

The next morning I had a delicious health food breakfast, I waved goodbye to the young people riding the horses, and continued driving west. Around noon I reached the main (and only) highway that connects Guatemala’s highlands with its Caribbean coast, and I hung a right. I was heading back up into the hills.

I was also, I realized with a totally self-satisfied start, totally, irrevocably, absolutely, incontrovertibly driving through Central America in my own private vehicle. Mexico—now retired people had been doing that in their RV’s since the Seventies. (Actually, what with all the stories about kidnappings and robberies, they probably hadn’t been doing that all that much since the Seventies.) Where I had driven to in Guatemala before—Atitlan and Antigua—had been obvious tourist areas. But here there was nothing touristy, and this was nobody‘s dreamed destination. This was nothing more nor less than everyday tropical Guatemala, with trucks and buses jostling each other on the road, with fields of tropical produce, with little concrete houses with red tile roofs, flowers of every color by the front gates, and banana palms dotted everywhere. Not to mention the powder blue sky with lacy white clouds.

And to think that I had gotten here by my little old lonesome self all the way from boring old December ridden Nashville, Tennessee. In a little more than a week. Damn right I should be pleased with myself. I had turned myself into a gosharoony Central American citizen of the world.

And, as such, what could be more natural than to take a left up ahead and mosey on over to Honduras?

This was supposed to be another of those roads that were more absent than present. But once again I was in luck, for in the past year Guatemala had been in the process of widening and paving it. As I hit the new stretch it was also once again soon apparent that Guatemala wasn’t just taking its highways up to Mexican standards. No, American engineers were clearly involved: Wide gravel shoulders, clearly marked central stripes, passing lanes (!) and, gasp, little night reflectors along the road sides. Needless to add that there were no topes.

I kept cruising on up and up into the higher and higher hills until I got two miles from the border. That’s where they were still working on the road. So between dodging the construction equipment and bumping, bumping, and jerking on the last original section, that took a half an hour. But I cleared Guatemala Customs relatively painlessly, and then slowly rattled the half mile over to the Honduras station.

This had always been a very minor border crossing, so all the various Customs windows were all together in one little patio area. All around me it was hot and quiet. Real quiet. Dogs slept listlessly under trees. A big new sign on the side of the building said that if anyone tried to hit me up for a bribe, I should call this number in Tegucigalpa, and they would send somebody over to beat the crap out of whoever it was who tried.

But these guys were all lazy and friendly and helpful, and even though there were a few vehicles ahead of me, I could tell that they probably didn’t get too many Tennessee license plates passing through. So when it came my turn they went out of the way to direct me to each of the next windows, to carefully fill out each receipt, and to then wish me a wonderful time in Honduras.

Those American engineers hadn’t made it across the border yet, so it was a painful bumpy ten mile drive down the hill to the town of Copan, population about 8,000. But I was in no hurry, since this was to be my destination for the night. I rolled in around four, found myself a clean, decent room for ten dollars, and then strolled around downtown.

Copan was quaint, and they intended to keep it that way. ‘They’ being all the Europeans and North Americans who had moved here. Not that there were really that many of them. But they had opened various bakeries and restaurants and hostelries, and there was a hell of a lot classier of a vibe about the place than you’d find in most Honduran towns. So it was relaxing to poke into a few places, sit around the square for a while, and wait for It.

‘It’ being Gore’s concession speech, which was due to happen at eight o’clock. For however much I had wanted to run away from all the insane intensity of the recounts and the court battles and the talking heads and the disgusting behavior by my political enemies, and however much I had actually succeeded in doing so, it had still filtered in through the headlines of Mexican newspapers and the occasional flicker of radio or television that I had caught. So I knew quite well and fully that the whole thing had reached its sad denouement.

At five to eight I was back in my small hotel’s common room, where the satellite TV was tuned into ABC News. And there I sat in a town by an insignificant border crossing in Honduras while Mr. Gore gave his noble and painful surrender. It was a perfectly fitting end to the perfectly surreal drama.

The next morning I had a whole day to waste, so I lay around doing nothing for a bit. Then I ambled over to one of those German owned bakeries. The term ‘baked goods’ anywhere south of the border is virtually always an oxymoron, so if you ever see an actual European running a shop, gorge yourself. I did.

Then I hung around some more. And finally around noon I walked the mile or so over to the entrance of the Copan Mayan ruins.

What? Why, after my vicious panning of Tikal, would I want to waste my time with more of the same? First, I had always wanted to, uh, see them, since Copan is about the third most important Mayan site. Second, it was right on my way.

Third, as I found out as soon as I entered the area, I kind of liked this presentation. Sure, it was the same old temples and ball courts and carved stone and hieroglyphics, but the Honduran authorities had cared not a whit about making it all look ‘authentic’. Perfectly mown lawns surrounded the various ruins, and well paved pathways connected them. There were plentiful modern litter baskets and pleasant guards everywhere. What’s more, you knew that there was a town of 8,000 people right next to you. It all had the effect of a clean outdoor museum, which was all the more amazing when you considered that it was probably the tidiest place in the entire country.

I know that one isn’t supposed to like such artificially gussied up versions of the past. But somehow it strangely worked for me. After all, I’d rather see one of their ball courts and imagine people having fun on a warm Sunday afternoon. Having just watched the humiliation of Al Gore, I didn’t need any more reminders of gruesome rituals.

Copan thus became my second favorite Mayan ruins, and I dawdled about a bit more. Then I walked back into town and wasted more time hanging around the square. Then it was back to the hotel, where right on time at around seven my niece showed up.

Valerie had been in the Peace Corps here in Honduras for a couple of years, and then when her hitch was up she had stayed on, inasmuch as she now had a Honduran boy friend named Heider. Who had come along with her out to Copan to meet me. Together we were all going to tour the country for a few days.

Since they had already seen the ruins before, they were good to go the next morning. So after fortifying myself with the last good breakfast I expected to have for a long time, we struck out for Honduras’s Caribbean coast.

This took a few hours. And when we reached it, me being me, I had to take the road all the way to its humid end. We were rewarded with the moss encrusted remains of a sixteenth century Spanish fort, the upkeep for which the Honduran government had spent a lot less money on that it had spent on Copan. Then it was back ever so slightly inland to the Honduran metropolis of San Pedro Sula.

Honduras is one of those few countries in the world where the capital city is not the largest one. (Ecuador is another, with Guayaquil larger than Quito. But if you go through them all, there really aren’t that many.) And the fact that you haven’t heard of it doesn’t mean that San Pedro Sula isn’t by far the most economically important place in the country.

Historically this had always been due to the presence of the large Lebanese immigrant community here (another strange fact for you to know). But in recent years there had emerged a far more dramatic phenomenon: The construction of gigantic textile maquiladora factories, in which now virtually every bra, panty, and t-shirt consumed in North American was sewn.

I could see one of the principal results of all this as we drove along the main perimeter road. Here there wasn’t just the token McDonald’s or KFC that one might expect in a large Third World city. There was block after block of virtually every fast food franchise you could imagine, from Arby’s to Wendy’s, and then up to and including Chili’s, Applebee’s, and even a Ruby Tuesday’s. Each looked exactly the same as it would in the States, complete with lawns and hedges and plenty of free parking.

You didn’t get this with ten interconnected families at the top ruthlessly exploiting hundreds of thousands of innocent workers. Somehow a middle class was being created from all these textile mills, which I figured must be a better outcome than if they had not been created.

What wasn’t so good was what happened every time we halted at a traffic light. Then swarms of eight year old boys would stumble up to each stopped car, weakly put their tiny palms to the window, and with a glassy eyed look say, ‘Uno lempira…’ (That’s worth about three cents.)

Ah, the glue sniffing lads of Honduras. I’d read about them before I’d come. Abandoned by their families for whatever reason, they drifted to San Pedro Sula and Tegucigalpa, where they all sat around sniffing glue together until their little brains fell apart and then they died within the year or so. Well, at least it keeps them off the street.

Oh, no, it looked like it didn’t.

This was about as pitiful and painful as life gets. So I did what one learns to do if one travels much around the bottom scrapings of the Third World: I blocked it out of my mind. And I turned into the Ruby Tuesday’s parking lot, since I figured that they’d have a good salad bar.

Which they did. Plus they had really good air conditioning. And there were happy middle class Honduran families around us, with the little children all bright eyed and glad that their dad had an executive position at the textile company.. Valerie and Heider and I tucked into our meals.

Afterwards, it was time to find our way around the greater San Pedro Sula metropolitan area, since our destination for the evening was La Ceiba, which was about eighty miles further along the coast. Valerie, being a true Folz, assured me that I didn’t even need to look at the map. Because she absolutely knew a shortcut through it all.

An hour later we were actually further away than when we had started, and Valerie was hopelessly lost. But we did have the good fortune, if that’s what it was, to be right next to one of those maquiladora factories. It was an immense, though seemingly thrown together in a couple of days, grey sheet metal building with a grey sheet metal roof that seemed to stretch on for acre after acre. And it was shift changing time, which meant that thousands and thousands of poor Hondurans were leaving the building, whilst thousands and thousands more were entering. It was a scene at once Dickensian and yet evocative of the herds of wildebeests on the Serengeti.

I pulled over and got out the map, made a few calculations, headed north and then on the cutoff west, and at around eight we were in La Ceiba, population circa 100,000. I was even able to find a hotel with interior parking. Of course, that meant about ten minutes of backwards and forwards and slightly left and slightly right as several Hondurans guided me into my spot. When I finished mine was one of about twenty vehicles squashed together inches apart for the night. And it was painfully clear as I looked around at the others that even after almost two weeks of nonstop mud and dirt driving, my beat up van still looked like the classiest wheels in town.

The plan was to get up the next morning and catch the ferry out to Roatan, the largest of the Bay Islands. These English speaking low lying Caribbean islands were reputed to have all the palm trees and white sand that one could hope for, and Valerie, having had been there several times, vouched for their wonderfulness. She also absolutely assured me that the ferry left at nine-thirty. So when I arrived forty-five minutes early (to be sure to have time to park the van) imagine my surprise to see the ferry chugging off towards the horizon.

Valerie swore up and down that the ferry used to go at nine-thirty, and maybe she was right. After all, the Third World tends to be that way. But now we had the problem of what to do with the weekend that we were no longer going to be having on Roatan. I got out the map.