Coed Week Revisited

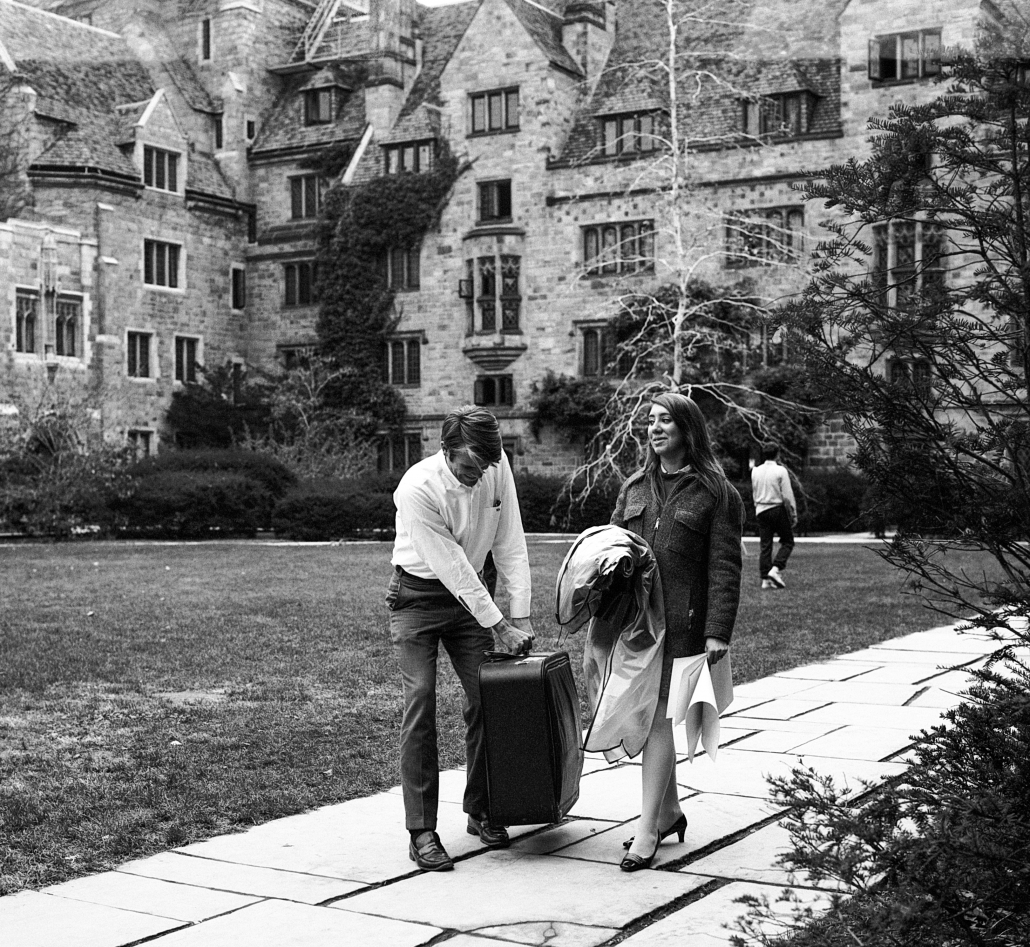

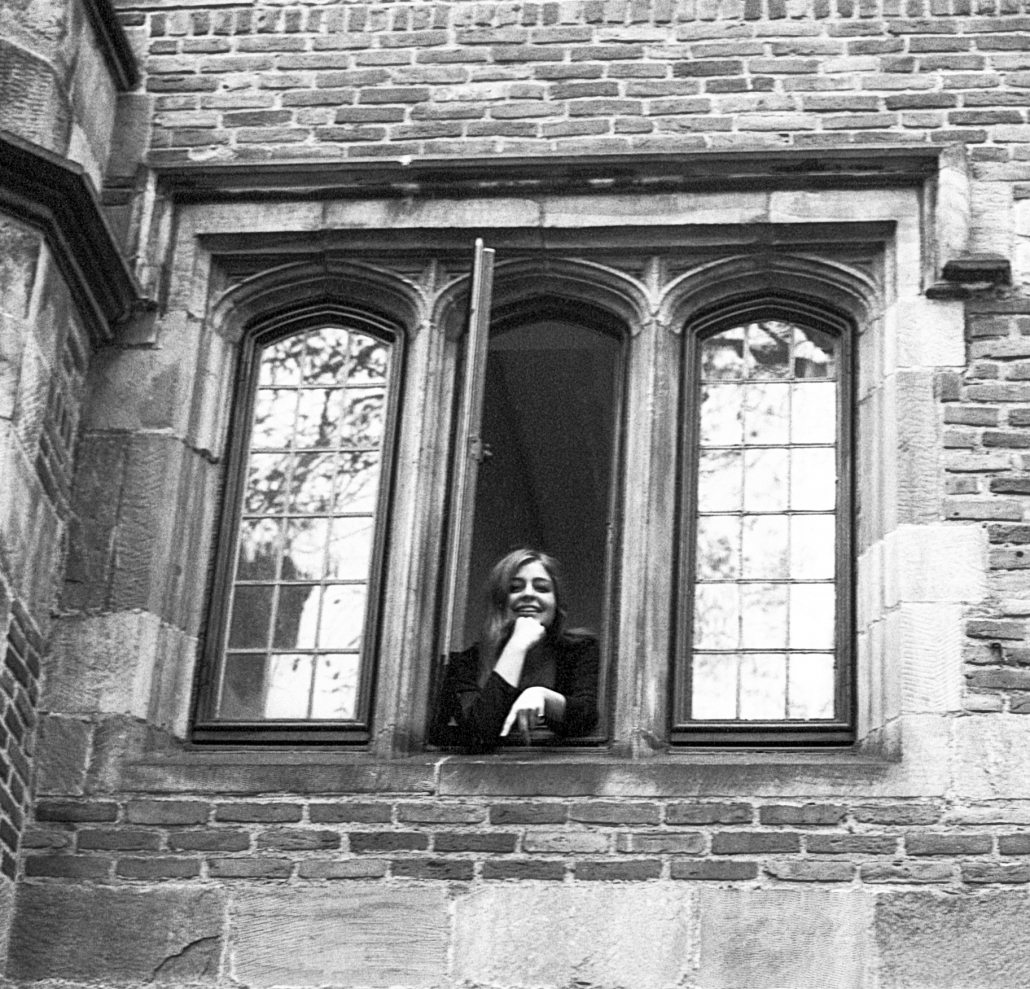

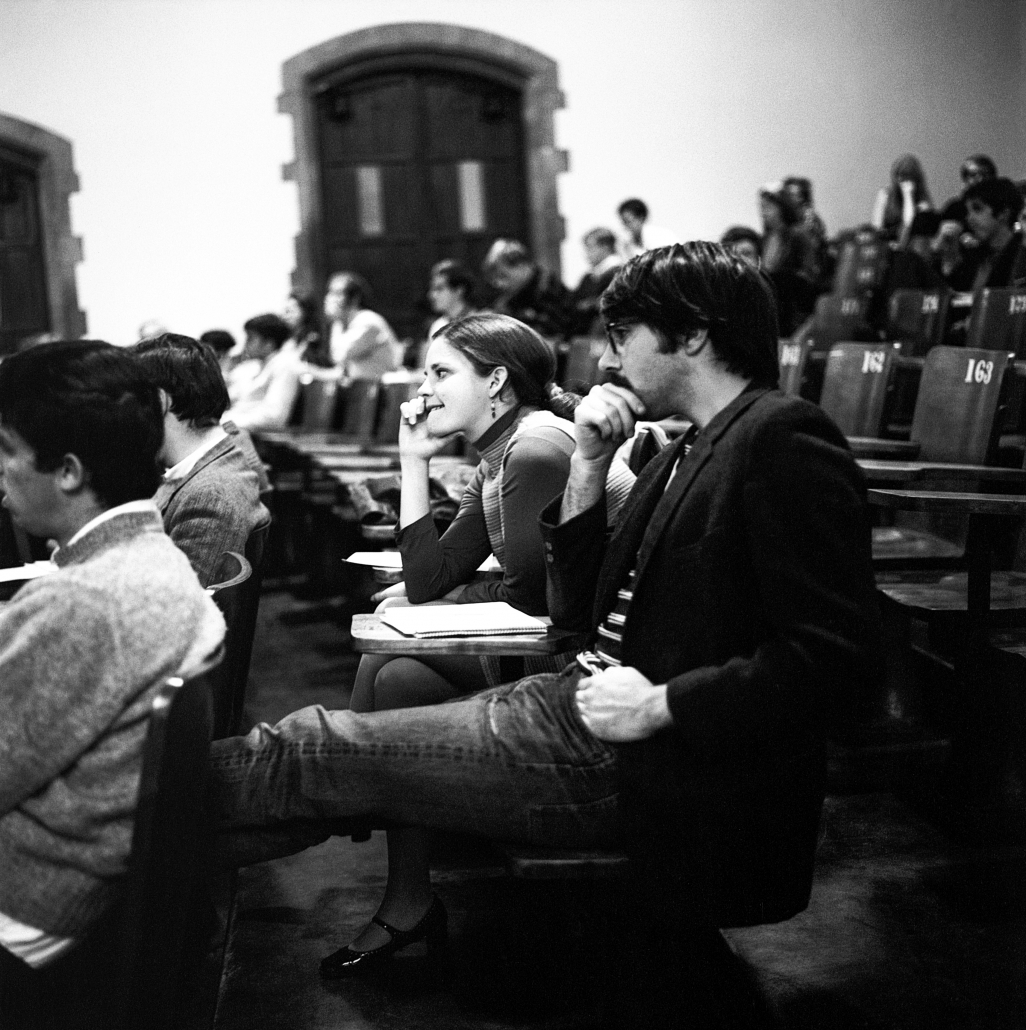

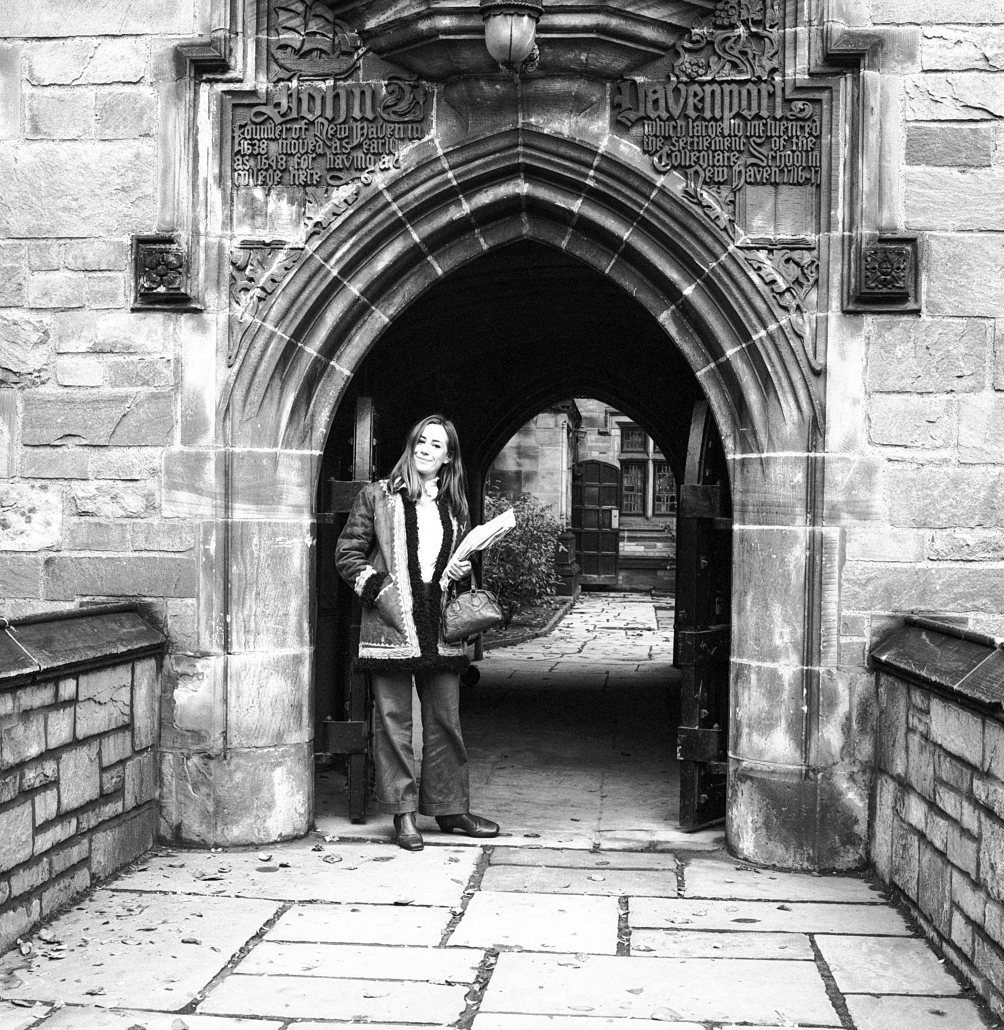

Yale Co-Ed week occurred during the fall our senior year. Co-Ed Week brought 750 women from 22 different colleges to the Yale campus. They stayed in the dorms and attended classes. For a brief moment in time Yale became co-ed.

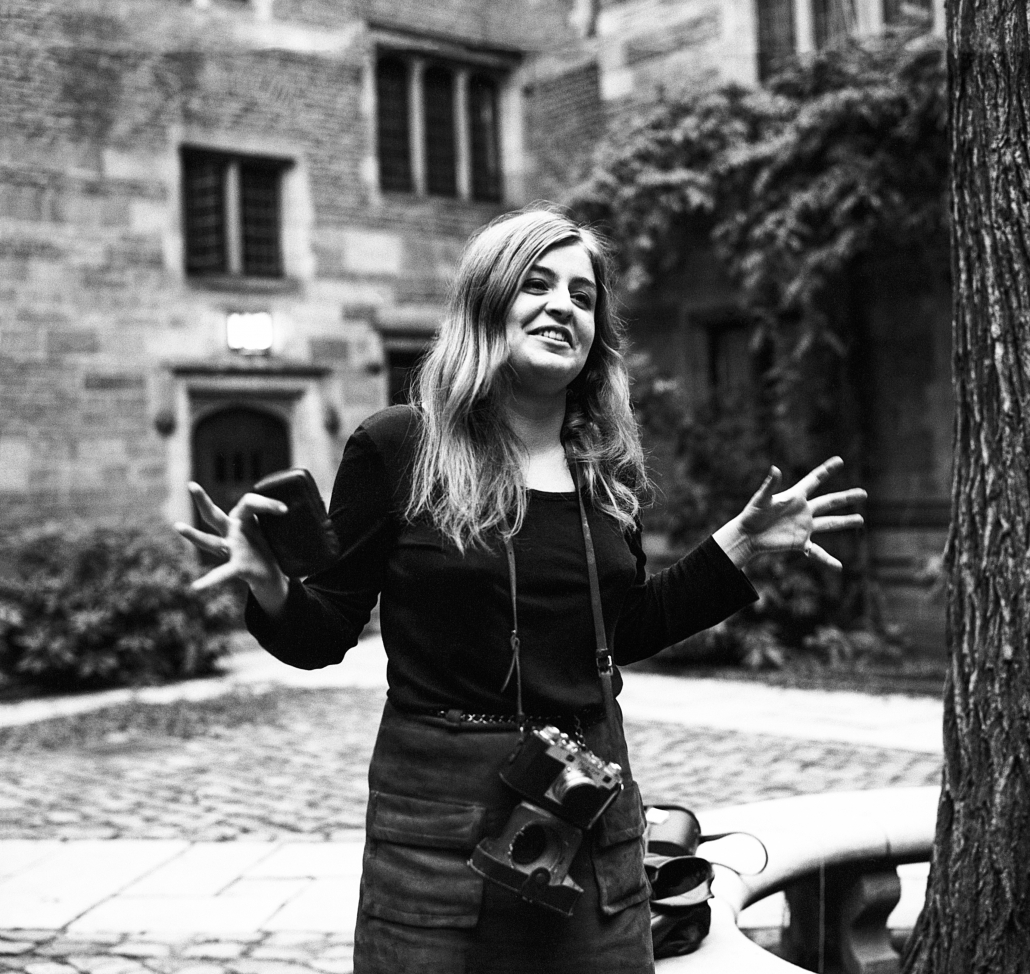

My perspective on Co-Ed Week comes from being a “stringer” for LIFE Magazine, hired to cover this raucous and marvelously in-your-face celebration of true change. These are my photographs and reflections on the event, and on its meaning to our class and to Yale.

In response to almost two years of protests agitating to make Yale co-ed, in late September, 1968, the Yale Student Advisory Board voted to host ‘Yale Co-Ed Week’ during the first week in November. Within hours of this announcement, LIFE Magazine “deputized” about a half dozen Yale undergraduates, who were taking a photography class taught by LIFE Magazine photographers, to be their on-campus “photog stringers.” We were given LIFE Magazine Press Passes and asked to fan out across campus to cover the event. Fan out we did.

It was fun, but like Yale’s famous (and infamous) course, Daily Themes, we had assignments and deadlines. No late submissions!

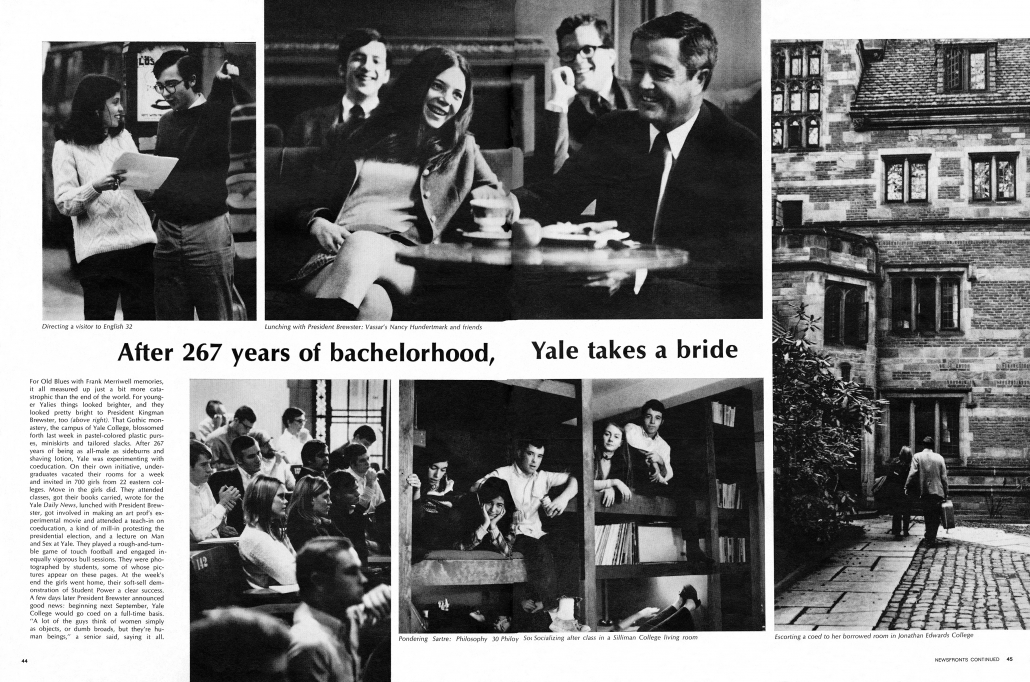

LIFE Magazine ● November-22-1968 ● Volume 65, Number 21, Pages 44 – 45

Co-Ed week began on Monday, November 4th, 1968. Exposed film rolls were collected at LIFE’s temporary Co-Ed Week Project Headquarters in Silliman College at 5:00 PM and driven to NYC for overnight processing. Developed film and contact sheets were returned the next morning at 8AM.

We were expected to be there to pick up our contact sheets and receive the next day’s assignment. For late-sleepers, the real world of assignments and deadlines was figuratively and literally a rude awakening. Our last film rolls were hand carried by couriers to LIFE at 5:00 PM on Friday at the end of that week. Lay-out review occurred in New Haven on Wednesday of the following week, and on the third Friday in the month (LIFE’s regular press-time), our two-page spread, shown above, landed on newsstands all over the world.

We had to juggle our regular academic assignments with our very non-routine shooting assignments. We often followed LIFE’s on-assignment writer, Jon Neary, who had been billeted to New Haven, as he walked around campus taking notes and conducting interviews. Jon frequently asked us, “Are you getting good pictures?” We quickly learned to shoot back, “Are you getting good words?”

The entire week felt like a camera safari as we attempted to capture meetings with people with whom the general public might be familiar, such as Yale’s President, Kingman Brewster, and the University Chaplin, William Sloane Coffin.

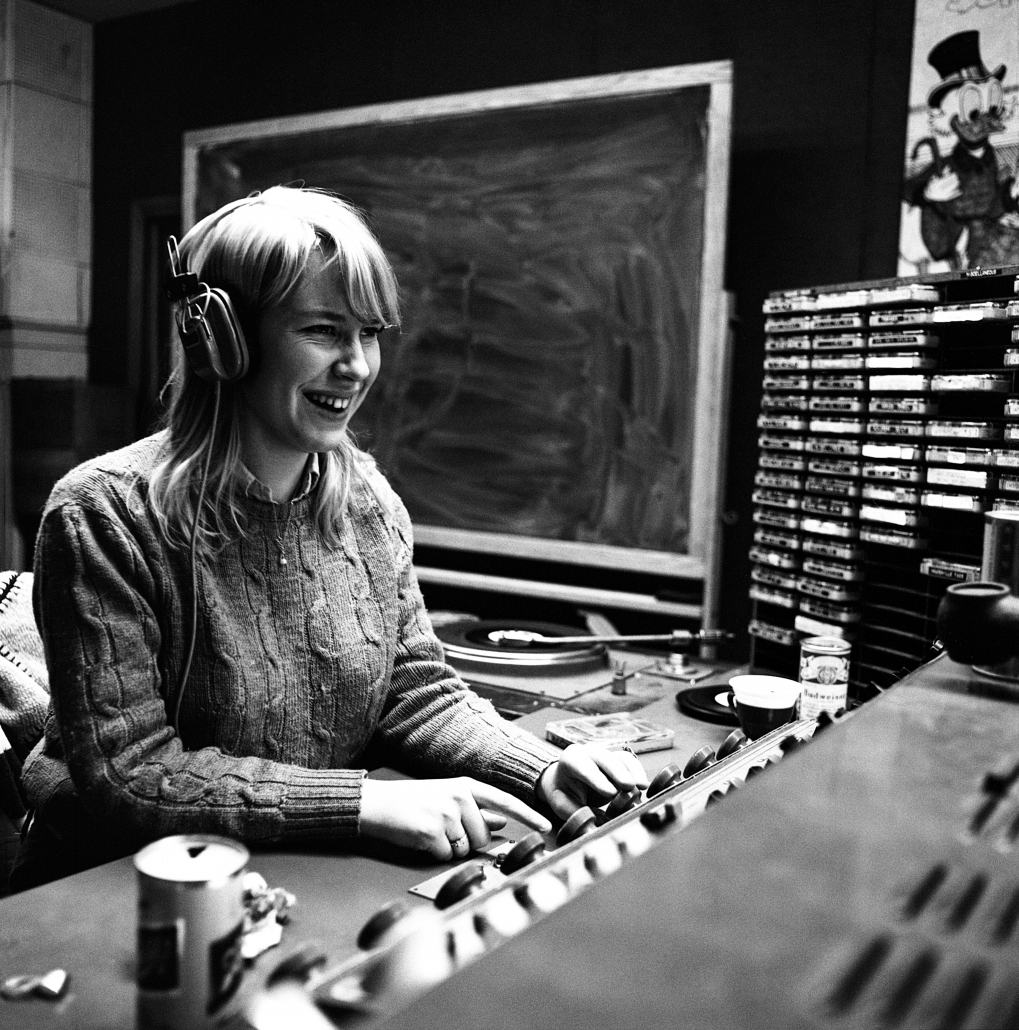

LIFE also wanted images showing women’s involvement with campus life, such as moving into the residential colleges, working for the Yale Daily News, announcing on WYBC, attending classes, and being a presence on campus.

LIFE paid extremely well! With the money I earned from this assignment, I bought my first new Hasselblad (which is why most of these pictures are square format). But more than the financial gain, that week taught me about the power of story-telling with pictures. My first three years at Yale were all about (and as a science major, it seemed, only about), words and numbers. But, even in science, images propel the narrative forward in ways that neither words nor numbers alone can. I now use images every day in my scholarship, teaching, and environmental advocacy.

LIFE’s coverage of Co-Ed Week, and their decision to use the student participants IN the event as cub reporters to tell the story OF the event profoundly changed how I communicate. Like so many of our experiences at Yale, we changed the institution as well as ourselves in the process.

Reaction to our article was swift. Most of the comments were congratulatory, “Go Yale!” and “It’s about time.” As recorded in our Year Book by class essayist Joe Green, however, reactionary responses were also full-throated. One antediluvian 1926 alumnus congratulated our Class of 1969 as “being the last true class of Yalies.” To put it mildly, however, we saw our accomplishment differently! Conventions for convention’s sake (like jackets and ties at dinner) had no place in a thoughtful institution, nor did the exclusion of women. Get rid of the conventions, get real!

Throughout the week there was a palpable sense around campus that the world we lived in was changing fast, was changing forever. Bob Dylan was in the air, “For the times, they are a changin’.” The campus had been racked by anti-war protests, civil rights demonstrations, and environmental rallies. But our involvement with the women’s rights movement was different.  As an all-male Ivy League College, Yale had a real horse in that race. For 267 years, Yale had intentionally, overtly, and proudly excluded women from its halls of power. Yale was part of the problem; we had to be part of the solution. By making co-education its focus, Yale activism took center stage. The national news coverage was intense. We were not just watching the 6 o’clock news, we were the 6 o’clock news. What we did that week was not just of local interest, it became international news. The article in LIFE propelled our class to center stage.

As an all-male Ivy League College, Yale had a real horse in that race. For 267 years, Yale had intentionally, overtly, and proudly excluded women from its halls of power. Yale was part of the problem; we had to be part of the solution. By making co-education its focus, Yale activism took center stage. The national news coverage was intense. We were not just watching the 6 o’clock news, we were the 6 o’clock news. What we did that week was not just of local interest, it became international news. The article in LIFE propelled our class to center stage.

What happened that week in New Haven was no longer a sideshow to protests taking place elsewhere, such as at Columbia University, on the Washington mall, or at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. We were ground zero. If we could change Yale, we could change the world. And we did.

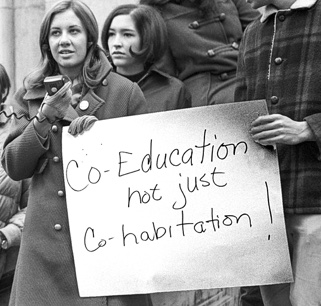

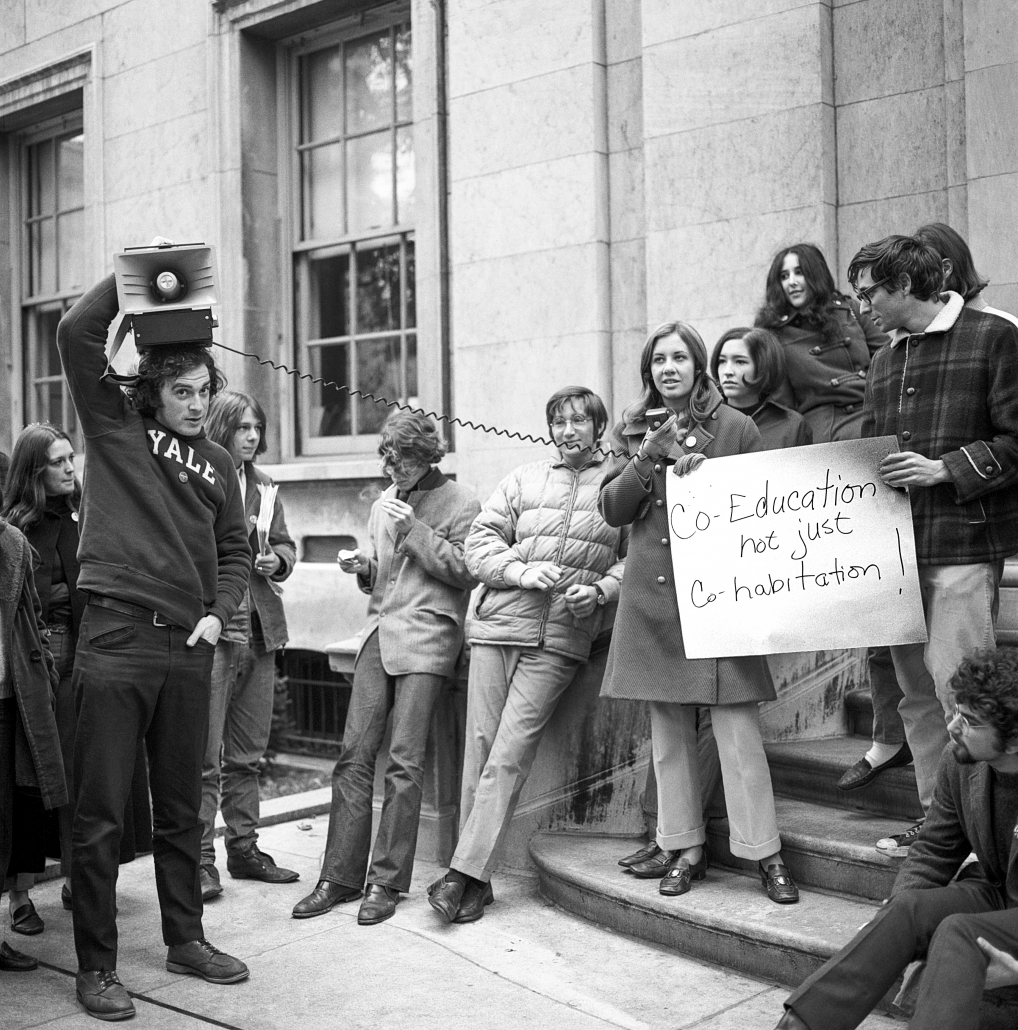

And we wanted this change now, not later. Many of the other movements we were involved in were making slow progress, not this one. As the article said, “After 267 years of being as all-male as side-burns and shaving lotion, Yale was now experimenting with co-education.” Our classmates and their women visitors made their voices heard at Beineke Plaza for “Co-education, not just Co-habitation.” We wanted overnight success. Both figuratively and literally, we got it.

We were glad when the women arrived, and sad when they left. When it was over, our classmate, Paul Taylor wrote an opinion piece in the Yale Daily News entitled “Coeds leave town, Yale sad for loss.” In it he commented that, “The presence of women on campus had caused men to realize that they had existed here abnormally for far too long.”

We were glad when the women arrived, and sad when they left. When it was over, our classmate, Paul Taylor wrote an opinion piece in the Yale Daily News entitled “Coeds leave town, Yale sad for loss.” In it he commented that, “The presence of women on campus had caused men to realize that they had existed here abnormally for far too long.”

This sentiment was so widely and so powerfully felt that the day after co-ed week ended, 1,000 students demonstrated on cross-campus in support of Yale’s immediate conversion from an all-male institution to a co-ed institution. President Kingman Brewster, megaphone in hand, responded by announcing that women would be admitted to Yale in the fall of 1969. Henceforth, he said, Yale application forms would be sent to any student who requested them, regardless of gender. This was revolution! We had just flung the doors of Yale College wide open. Revolution felt good! Victory felt sweet.

Three days after our November co-ed week and after our semester-long protest in favor of co-education, Kingman Brewster announced to the Yale Corporation and the world, that the following year, Yale would admit its first women undergraduates. In one fell-swoop our class changed Yale more than any other class before or since.

Three days after our November co-ed week and after our semester-long protest in favor of co-education, Kingman Brewster announced to the Yale Corporation and the world, that the following year, Yale would admit its first women undergraduates. In one fell-swoop our class changed Yale more than any other class before or since.

In one fell swoop, our class changed Yale more than any other class before or since.

See you at the reunion!

from: https://yaledailynews.com/blog/2019/02/25/through-the-glass/